The term “distributed energy resource management system,” or DERMS, is used to describe a wide array of software platforms serving a number of functions, from controlling and aggregating fleets of behind-the-meter energy assets, to enabling utilities to integrate these distributed energy resources into their grids.

But according to GTM Research’s newly released North American DER Management Systems 2017 report, a true “enterprise DERMS” platform -- one that includes all of the above, without kludgy multi-vendor integrations, and outside the realm of pilot projects -- doesn’t exist today.

“This isn’t about interconnection or hosting capacity analysis, operations and maintenance, or long-term management of distributed energy resources (DERs) -- this is about how we manage the grid and DERs in real time,” said Ben Kellison, director of grid research at GTM Research, referring to a new set of categories used in the DERMS report. “Because of the definitional change, we became more stringent about what we call spending on these solutions.”

Applying this to GTM Research’s new North American DERMS market forecast yielded a “pretty bleak” figure, he said -- a little over $380 million in cumulative spending through 2021. That’s not much more than the $300+ million in venture capital investment raised by DERMS-related companies since 2010.

The forecast also reflects slower-than-expected progress in DER-to-wholesale-energy market integration in Texas, and early-adopting utilities that have hit regulatory and technological hurdles that have pushed spending into future years. San Diego Gas & Electric, which started its $57.4 million DERMS project in 2012, appears likely to spend half or less of that amount by the end of 2018, to take one extreme example.

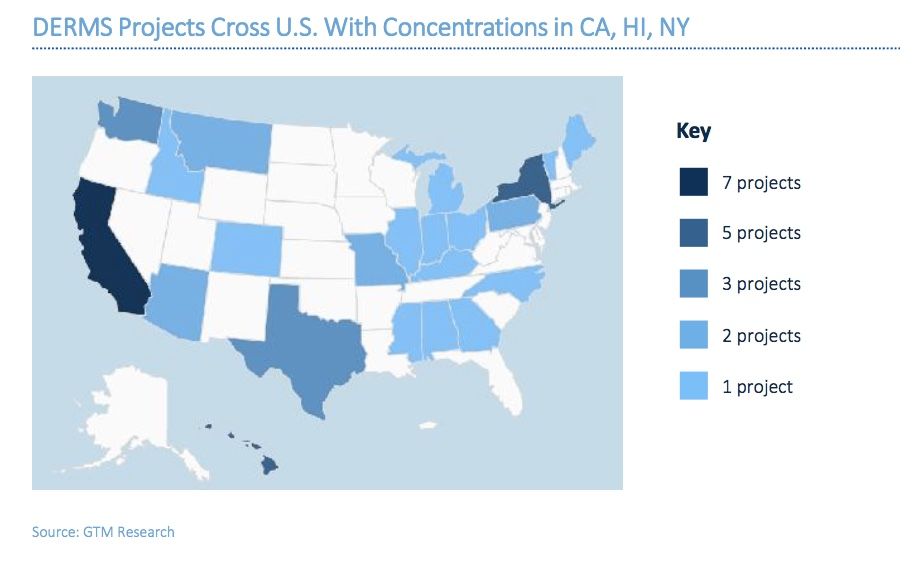

At present, the majority of projected spending is for pilot projects and demonstrations, and the report notes that it will likely be two to three years before an initial set of utilities pursues full deployments, with broader adoption occurring beyond 2021. DERMS activity has been largely concentrated in a handful of states that are aggressively addressing distributed energy integration with major policy reforms, including California, Hawaii and New York. Texas and Washington state are close runners-up, however, and 17 states have at least one pilot project underway.

Still, these low numbers belie the growing need for DERMS solutions, Kellison said. “There are more and more DERs on the grid, more and more controllable loads on the grid. And with things like solar PV that have interacted completely passively with the grid, they’re having some of their value streams questioned in some states, or altered in other states. So they’re having to seek out additional values.”

GTM Research defines the existing DERMS landscape in three categories: edge, fleet and central. Central DERMS are extensions of the distribution management systems or advanced distribution management systems platforms that give visibility and control to utility operators today. Notable examples include Pacific Gas & Electric choosing General Electric to build its DERMS platform, San Diego Gas & Electric’s work with Colorado-based startup Spirae, and Hawaiian Electric’s partnership with Siemens on its SHINES distributed energy-grid integration project.

Kellison noted that GE and Siemens fall into the category of companies for which DERMS is just one piece of a much broader set of software and equipment business with their big utility customers. While the DERMS-specific spending may be low, it often comes as part of larger deals. “They’re not all chasing $25 million or $40 million contracts," said Kellison. "They’re chasing more than that.”

Edge DERMS setups, also known as “active network management” systems, take the utilities a step further into DER control through SCADA controls to utility assets, and cellular- or broadband-to-Wi-Fi connections to behind-the-meter assets. These are faster-acting, and require some amount of edge computing to manage the task of getting lots of devices to act in concert with local and system-wide grid needs. Some vendors rolling out this kind of system include Smarter Grid Solutions with Southern California Edison, and, as GTM Research understands it, Enbala Power Networks with one of California's big three investor-owned utilities.

Fleet DERMS is the broadest category, and includes software that can enable utilities or aggregators to dispatch lots of DERs for economic opportunities. Notable examples include San Antonio, Texas-based CPS Energy’s work with AutoGrid to manage up to 165 megawatts of diverse DERs and controllable loads, and New York utility Con Edison’s work with Sunverge on its non-wires alternatives pilot. This category also includes a number of alternative descriptions, such as DER aggregation, or (if it can meet certain energy, ancillary services and reliability needs) virtual power plants.

Finally, there’s the enterprise DERMS category, which essentially includes all three previous categories in a unified platform to “manage all DERs on the grid across customer, utility and wholesale market objectives.” This doesn’t really exist yet, although Texas municipal utility Austin Energy’s Department of Energy-funded SHINES project comes close. Austin Energy's use of Doosan GridTech’s platform to manage residential, commercial and utility DERs, on its own and through aggregators, on both economic and reliability measures, merits mention as a “partial fulfillment” of the description.

Other pilot projects are aiming at enterprise-level integrations, but as of today, “You can’t get everything packaged and organized in an efficient manner -- it requires multiple vendors to get there,” Kellison said. GTM Research has laid out a graphic that explains how central, edge and fleet platforms must evolve to meet the need for this grand integrated approach to managing DERs, shown below.

---

The North American DER Management Systems 2017 report mentioned in this article is part of GTM Research's Grid Edge Service. Learn more here.