When the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved Order 745 in March, elation blanketed the world of demand response.

Fair play! More compensation! Take that, old-school power generation! The ruling said that many grid operators will have to pay the full market price, known as the locational marginal price, to economic demand response resources in real-time and day-ahead markets as long as dispatching DR is cost-effective.

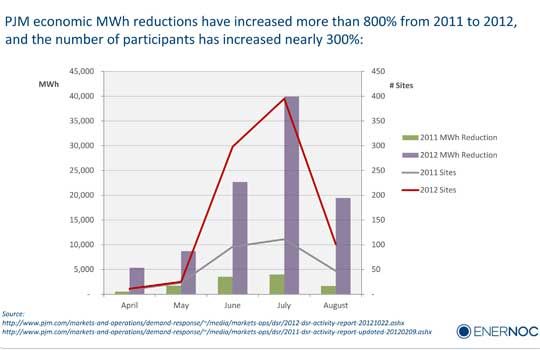

A year and a half later, the hard work has settled in and there are only two regions in the U.S. where the ruling has so far been implemented. The news so far, however, could not be better, Brendan Endicott, director of economic demand response at EnerNOC, suggested during a webinar hosted by Restructuring Today entitled "How Big of an Impact Did Order 745 Have This Summer?"

“Prior to 745, demand response was just tacked on to the side” of markets, he noted. Now, at least in PJM Interconnection, the grid operator that covers much of the mid-Atlantic, demand response is a fully integrated offering.

In PJM, total economic energy reduction has increased by 800 percent in the past six months. For demand response participants, payments have increased nearly 400 percent from 2011 to 2012 even though energy prices are 20 percent lower in the same period of time. “It basically shows that as a result of the order, the proper incentives are there to get people into the market,” Endicott added. Economic demand response participants in PJM have netted about $6 million since April.

In ISO New England, there have been some changes, primarily an extension of the day-ahead load response program, but demand response cannot yet set the locational margin price.

Forget about the other grid operators, NYSIO, MISO, SPP and CAISO; they’re still working out how to implement the ruling.

When the rest of the grid operators figure out how to incorporate the new requirements for demand response, it will be a glorious day for negawatts.

Or will it? Paul Centolella, VP of Analysis Group and former commissioner of the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, had a far less rosy and more critical look at what the ruling meant for the future of demand response. “We can very quickly see that it was not an efficient way to incent demand response within the market,” he said.

But what about all those rosy figures from PJM? Well, it depends on how you define demand response.

Centolella noted that the winners were largely large commercial and industrial customers. By paying the full LMP, he argues that it incents self-generation over efficient regional dispatch and is actually discriminatory.

Order 745 does not even get close to the larger issue of how to optimize demand across the entire spectrum in a much more dynamic way, Centolella argues. “Most of our end-use devices are intelligent in some way,” he said, noting the variety of gadgets in our lives that have chips in them. “If we could take advantage of that capability, we could have a more resilient grid.”

In other words, Centolella sees Order 745 as a somewhat distracting market mechanism when the real effort should be in enabling demand response into every facet of our lives, rather than a system that only reduces demand during peak. He argues that improving load factors through a demand optimization strategy is the only way to close the glaring investment gap that the grid faces.

He sees automated demand response, standardized formats for energy usage and on-bill financing for energy efficiency upgrades as programs that can help push toward a truly optimized grid. But many real world examples, from an OpenADR standard to the Green Button initiative, are in the very early stages.

So how do you move to a more integrated grid, where demand does not just respond but acts as an integrated facet of the system? “The answer really lies in creating a framework for collaborative innovation,” says Centolella. “It depends on changing the focus of our vision to ‘How do you create more efficient markets?’ and not just ‘How do you create more demand response?'”