California is already busy creating new regulations and market structures to integrate rooftop solar, behind-the-meter batteries, plug-in electric vehicles and fast-acting demand response systems into its grid. This week, California’s grid operator took another step down this path -- one that could allow these resources to tap the state’s grid markets as a revenue-generating resource, possibly as early as next year.

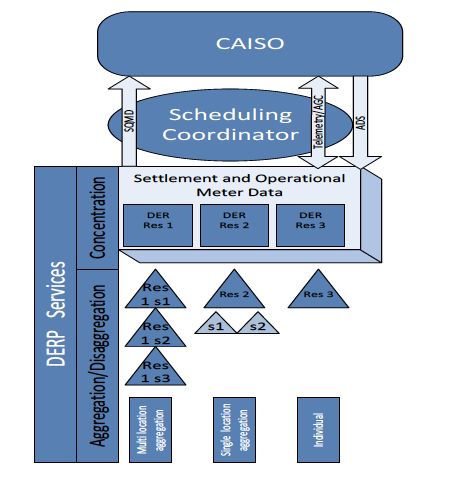

On Wednesday, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) published a proposal (PDF) for creating a new class of grid market players, known as distributed energy resource providers -- DERPs for short. In simple terms, the proposal sets rules for how DERs can be aggregated and dispatched to serve the same grid markets open to utility-scale energy installations today.

That’s something that no other state has done, although some, including New York and Texas, are working on similar plans. But California may be moving more quickly from concept to reality -- if only on a limited scale.

CAISO’s board is set to vote on the draft final proposal at its July meeting, which would set the stage for requesting approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for the changes needed to put the DERP classification of market participant into effect, Lorenzo Kristov, market and infrastructure principal at CAISO, said in a Wednesday interview. If that’s forthcoming, “by the early part of 2016, parties could start using it,” he said.

But to move this quickly, CAISO has put some constraints on this new class of grid player, he noted. These include caps on the size and scale of their aggregations, as well as a requirement that any serving more than a single grid pricing point must be limited to a single type of technology. These may limit the utility of systems that connect solar systems, batteries, EV chargers, smart thermostats, and other integrated energy assets.

California is full of companies eager to put their distributed energy resources to money-making use as grid resources. One well-known example is SolarCity, which is promising to share future grid revenues with customers installing Tesla Powerwall batteries alongside their rooftop solar systems. Battery-solar partnerships, like those SunPower has inked with Stem and Sunverge, are no doubt exploring the same possibilities.

Demand response companies like EnerNOC and Johnson Controls have been participating in CAISO’s DERP proceeding, which makes sense, since California is in the midst of revamping its demand response rules in ways that could open up new business models and revenue opportunities. There’s also potential for home automation platforms from companies like Nest or Alarm.com, or grid-responsive EV charging systems, to become pieces of the DERP puzzle.

But any company considering its future as a DERP will have to weigh the costs of networking and controlling customer-sited distributed energy resources against the potential benefits of earning grid market revenues from participation. Here’s a breakdown of how CAISO has structured its plan, why it’s set the limits it has on how DERPs can participate -- and how it’s expanded some parts of its final proposal to meet stakeholders’ desires for a more varied mix of resources to play a role.

From ISO-metered to internet-connected: Merging distributed resources into a system built for central control

The first thing to know about CAISO’s proposal is that it takes on some complex issues, arising from the move from single, large and transmission-connected resources like power plants, solar farms and utility-scale grid batteries, to a lot of resources scattered across the distribution grid.

CAISO’s current rules require grid market-participating generators and loads to be at least 500 kilowatts in size. It also imposes strict telemetry and metering requirements for them to respond to its energy and ancillary services dispatch system.

But the DERP proposal would set up a simpler and less expensive way to meter and communicate with lots of smaller resources, and to allow any party that can aggregate at least half a megawatt of them to respond to CAISO’s grid commands and get paid for it.

“We clearly see distributed energy resources playing a larger and larger role over time as part of the supply mix,” Tom Flynn, CAISO infrastructure policy development manager, said Wednesday. CAISO has been working on the issue since 2013, when it held its first stakeholder meeting to discuss a key issue barring DERs from joining in grid markets -- telemetry and metering requirements.

In a strict sense, “there’s nothing that precludes you from aggregating resources today,” he said. “But today’s rules present some burdens for anyone trying to do that,” and “one of those is that the underlying sub-resources have to be ISO-metered.”

ISO-metered systems require a highly accurate measurement system with a real-time communications link between each grid connected resource and CAISO’s operations center. That’s possible with big power plants and other utility-scale resources, but it’s far too expensive and complicated to do for individual DER-equipped homes and businesses.

To solve that problem, “we’re proposing that these DERP aggregations are scheduling coordinator-metered entities, rather than ISO-metered entities,” he said. A scheduling coordinator is an entity that’s set up its own methods for metering and managing energy resources, and has had them vetted and approved by CAISO.

And under the DERP proposal, CAISO will allow these entities to connect their fleets of DERs via the Internet, using approved communications and security protocols. “That’s a key advance, because it reduces some of the burden,” he said.

This kind of approach is already being tested out in California, through demand response pilot projects that aggregate lots of homes and businesses to turn down power use to respond to grid needs. These demand response projects will remain separate from the DERPs that could come into the market next year, but in both cases, “the scheduling coordinator has the responsibility of ensuring that those sub-resources are all metered, and that those meters comply with all applicable rules,” Flynn said.

As for telemetry -- the real-time communications link between CAISO and the grid resource -- the DERP proposal will not require it for systems under 10 megawatts in size if they’re seeking to play into energy markets only. For the more lucrative, but more technically rigorous, ancillary services markets, however, “a resource of any size is required to provide and maintain real-time visibility, and in the case of regulation, respond to the ISO’s Energy Management System (“EMS”) control signal,” the proposal states.

Sub-LAPs, PNodes, and the limits to mixing and matching different DERs as grid resources

Not all types of distributed energy resources will be able to join in the DERP mix willy-nilly, however. CAISO’s proposal has set some strict limits on how DERs will have to react to its commands, as well as what types of technologies can be aggregated across different parts of its grid network.

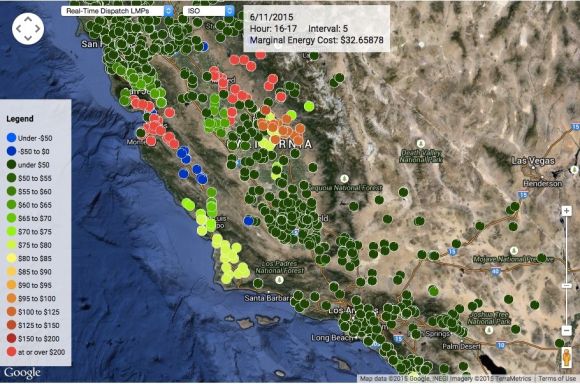

Discussing the limitations, Kristov explained that CAISO’s grid is akin to “a network of intersecting lines,” and that “every point where those wires intersect is a point where we have a price.” The same points are assigned to each spot where a generator connects to the grid, or where CAISO’s transmission system connects to the substations serving the lower-voltage distribution grids that carry electricity to end customers.

“Those things we call 'pricing nodes,'” or PNodes, and there are 4,900 of them scattered across California, more densely clustered in the most heavily populated parts of the state. Here’s a map of a subset of major nodes, indicating the wide difference in power prices from point to point on a summer afternoon.

Any collection of DERs will correspond to one or more of them, depending on how broadly a DERP chooses to define the aggregated load it’s making available as a resource. That creates a challenge for CAISO, because it won’t necessarily know whether a DERP that’s responding to a grid command is tapping resources connected to one PNode or another one, or as the proposal puts it, how a CAISO signal will be “disaggregated or decomposed” by the DERP -- and not knowing that is a problem for grid operators.

“If you have a whole bunch of DER at a single network node, whatever its behavior, its impact will be only on that one location,” Kristov said. “But if you have something that’s spread across a dozen nodes, then we would give a dispatch,” for example, requesting a bid for 5 megawatts of output, “but we don’t know if it’s going to be uniformly spread against those 12 nodes, or a predominance on one or two of those nodes -- and that unpredictability means we don’t know the impact on the grid.”

That led CAISO to cap the size of DERP aggregations across multiple PNodes to no more than 20 megawatts, and insist that all resources responding to a dispatch order move “in the same direction,” either up or down, Flynn said. In other words, if a lot of batteries are bidding into a request for power, they all have to discharge at once -- DERPs can’t allow some of them to keep charging up while others discharge.

But the most contentious limitation in CAISO’s proposal is its insistence that DERPs do not combine different types of DERs within a single aggregation. In other words, batteries have to be combined with batteries, EV chargers with other EV chargers, demand response with demand response, and so on.

“There are some very complex reasons why we can’t allow for that today,” Flynn said. A big one is that CAISO’s current software can’t model the congestion relief impacts of having lots of different resources responding in an unpredictable fashion. CAISO’s proposal (PDF) goes into greater detail on how “shift factors,” “generation distribution factors,” “load distribution factors,” and other such technically precise matters limit its ability to model “heterogeneous” resources in the power flow calculations and contingency analyses it must run before it sends out dispatch orders.

So, as recently as last month, CAISO’s proposal contained a blanket ban against mix-and-match DERs. But “the response from aggregators was, that’s not a very popular element of the proposal,” he said. “Many of them are thinking they’d like to aggregate rooftop solar, energy storage, batteries, demand response, and electric vehicle charging stations, because all of these things may exist in the home of the future -- and we were saying, you can’t do that.”

In response, “We were able to partially relax that limitation” in the final proposal released this week, he said. “If you put together a DERP aggregation that’s limited to a single PNode, we are allowing you to mix sub-resource types -- and we explained why we’re allowing that.”

Aggregations limited to one PNode are also unlimited in size, with individual DERs that can move up or down in response to a CAISO signal, as long as the “net movement of the aggregate” of the response adds up to what CAISO asked for. The question for would-be DERPs, of course, is whether they will have enough DERs connected to a single PNode for the minimum 500 kilowatts required to participate.

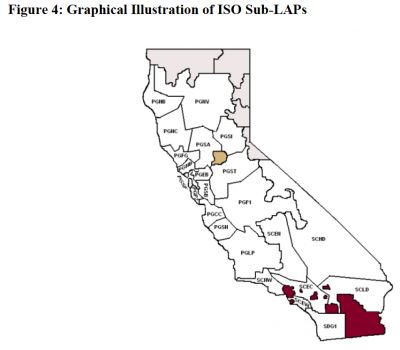

Prospective DERPs will also be limited in how they pull together systems that are scattered across California, by a rule that limits aggregations to a single sub-load aggregation point (sub-LAP). These are the roughly two dozen regions of the state where CAISO has determined that historic congestion patterns tend to lead to price divergences between two parts of a grid.

CAISO’s proposal points out that without this limitation, a DERP could respond to a dispatch order seeking to reduce transmission constraints between two sub-LAPs by turning on resources on the “wrong” side of the constraint, possibly making the problem worse.

All of these limitations have a common purpose -- to avoid unanticipated problems as CAISO embarks on a task it’s never had to manage before. Meanwhile, CAISO is working on a lot of other issues, like its broader demand response and energy efficiency roadmap, or its energy storage and distributed energy resource initiative (PDF), which are “about a lot more than just aggregation,” Flynn said.

But while the new proposal may be “relatively modest in scope, it accomplishes some important things as a first step,” Kristov said. “It creates an initial framework that we will seek to make enhancements to” in years to come. CAISO is taking comments on its proposal through June 24, and will vote on it during its July 16-17 board meeting.