In the past few years, a host of startups and IT giants have launched technology aimed at turning simple streams of customer electricity data into kaleidoscopic views of individual energy usage in homes and businesses.

These “energy disaggregation” technologies, now being tested in labs and utility pilot projects, promise accurate breakdowns of major loads in homes, like air conditioning, water heating, pool pumps and major appliances, without expensive sensors and networks to meter them all individually.

So far, these technologies haven’t tackled the distributed energy supply side of the equation, however. That's a shame, because homes with rooftop solar PV represent a growing and challenging set of customers for utilities. On Tuesday, Sunnyvale, Calif.-based startup Bidgely launched a solar PV disaggregation technology that it says can solve this problem, delivering accurate data on solar’s moment-to-moment impact on household energy use for customers and utilities alike.

Bidgely has been testing its solar disaggregation technology with several unnamed utility customers, and is now making it available to utilities that are delivering their customers smart meter data via the Green Button data standard, said Steve Nguyen, Bidgely's head of marketing, in an interview.

Customers using Bidgely’s HomeBeat home energy portal platform will be able to view their solar generation profiles alongside several key household energy loads -- although that data, as with all Green Button data, will most likely be at least one day old by the time it can be viewed.

Later this year, Bidgely plans to expand its solar disaggregation offering to home area network (HAN)-enabled devices, which receive whole-home energy data from smart meter local networks on a minute-by-minute basis, said Nguyen. That additional data granularity could allow for more fine-tuned disaggregation, as well as the possibility of more up-to-data information for homeowners and utilities.

But even day-old data can provide solar-equipped customers a lot of insight into their daily solar-energy usage relationships, he said. It can also give them a reason to log onto the web or mobile platforms that Bidgely provides its utility customers. That could be a boon to utilities worried about losing their solar-equipped customers to interlopers like third-party solar aggregators and energy services providers, noted Nguyen.

Beyond that, Bidgely is “in development on a number of functions on the utility side,” he said. “We’re using our disaggregation technology to fuel intelligence for the utilities. That will manifest in areas where you might expect, like customer service, knowing where loads are going with in-home appliances, gathering data by neighborhood and by region.”

Figuring out what’s going on with customer-sited, grid-tied PV is a big challenge for utilities in solar-rich states like Hawaii, California, Arizona and New Jersey. While some insight can be gleaned from combining solar installation data with daily weather data, that kind of analysis can’t provide accurate data on the individual home level.

Meanwhile, ”smart” solar PV inverters, sophisticated local weather tracking systems and home energy sensors can deliver accurate data, but with additional costs that might be hard to justify from the point of view of customers, solar installers/aggregators or utilities, he said.

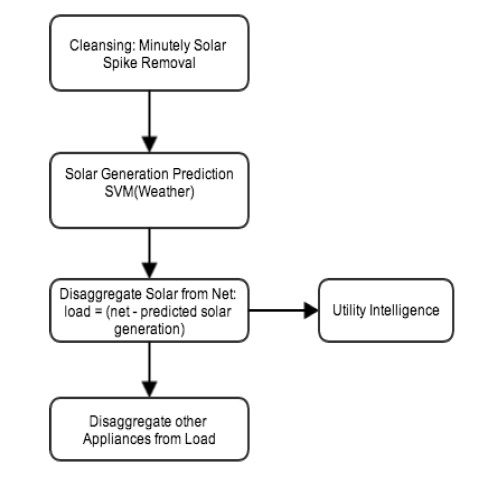

But how accurate can Bidgely get with the data it's able to analyze? Bidgely’s white paper (PDF), titled “Solar Energy Disaggregation using Whole-House Consumption Signals,” explains how its algorithms use net-metered energy consumption and weather data to deliver solar generation data.

Using methods to differentiate “peaks” in home appliance or HVAC energy usage with sub-hourly changes in PV generation caused by clouds, Bidgely was able to show accuracy of solar-home load disaggregation with error as low as 5.5 percent -- better than other methods outlined in similar research projects carried out in the past few years.

The white paper collected data from 137 homes from North American locales including San Francisco, Boston, New York, Canada, Kansas and New Jersey, as well as from several regions of Australia. That information could help interested parties "disaggregate" which utilities Bidgely is working with, though Nguyen declined to offer any more details on its existing utility partners.

As for how difficult it is to get this kind of accuracy, Nguyen said it would take competitors “years of man-hours to develop algorithms with our efficacy.” That doesn’t mean that Bidgely will be the only company to take on the challenge, however. It’s likely that other energy disaggregation players, including startups like PlotWatt, Navetas and Energy Aware, original technology developers like Enetics, and big companies including Belkin and Intel, may be interested in trying their own approaches.

So might solar aggregators like SolarCity, Vivint Solar and Sunrun, or home energy efficiency and customer engagement providers like Opower and Tendril. Or perhaps these players may turn to partners like Bidgely, Nguyen noted.

Bidgely has raised a total of $8 million in venture capital from investors including Khosla Ventures, and has worked with Stanford University on Department of Energy ARPA-E program-backed research into behavioral energy efficiency. Earlier this year it launched its “Freedom Summer” program, which offers utilities free access to its core customer energy disaggregation platform, and is automatically enabling its solar disaggregation to utilities that sign up.