Before AB 327 became the vehicle for a solution to California’s solar net metering impasse last week, it spent the summer as the target of attacks from the solar industry, as well as energy efficiency advocates, environmentalists and public interests groups. What united these groups in opposition to a proposed law with the stated aim of making the state’s power rates fairer to everyone?

The answer to that question is complicated, and rooted in the decade-old system that guides how the state’s investor-owned utilities -- Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric -- are allowed to charge their residential customers for electricity. But in simple terms, it boils down to two big changes that AB 327 would enable, both of which could damage the economic case for rooftop solar power.

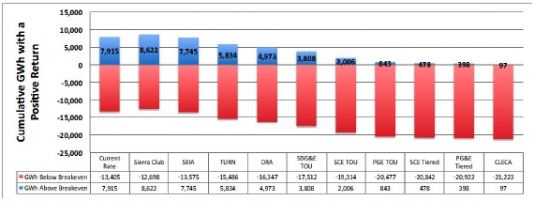

In fact, one analysis conducted for the Sierra Club found that recent rate proposals from the state’s big three utilities, all based on what AB 327 would permit state regulators to consider if it’s passed into law, could significantly undercut the cost-competitiveness of residential rooftop PV systems against electricity supplied from the grid:

According to this analysis, the overall effect of these rate changes would equate to adding $2.50 per watt to the cost of today’s rooftop PV systems, in terms of the reduced payback potential of those systems over their lifespan. That’s the equivalent of a 30-percent increase in the cost of a typical solar system, or enough to erase the value of the 30-percent federal investment tax credit for solar systems.

How could a simplification of utility rates lead to such a dire outcome for solar power? To explain, let’s take a look at how California’s residential utility rates are organized today, and what AB 327 would do to change them.

How Flattened Tiers Could Lower the Value of Net Metering

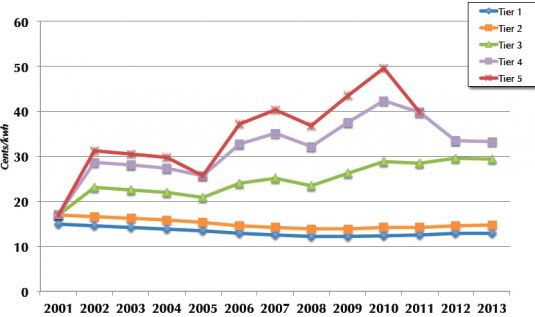

First of all, AB 327 would bring down electricity costs for those who consume the most power by changing the state’s current “tiered rate” structure. Set in place after the 2001 California energy crisis, tiered rates force residential customers to pay more for each kilowatt-hour of power, depending on how much they use per month. Those rates now range dramatically, from about 13 cents per kilowatt-hour for the lowest tiers, to as high as 33 cents per kilowatt-hour for consumption in the highest tiers -- and in years past, top-tier rates have gone as high as 50 cents per kilowatt-hour, as this chart of PG&E tiered rates shows:

The original purpose of AB 327, as introduced by state Assemblyman Henry Perea, D-Fresno, was to adopt a simpler, two-tier system to avoid sticking heavy power users with outsized bills. Specifically, the idea was to reduce power costs for customers in California’s hot Central Valley and other inland regions, where air conditioning power use drives many residents into the higher tiers during the summer months.

But while flattening tiered rates could be a boon for those forced to pay them, it could be a real problem for rooftop solar PV economics under the state’s net metering regime. Under net metering, solar PV owners are paid by utilities for the electricity they generate and sell back to the grid, at the same retail rates they’re being charged for the power they consume.

In other words, “High-use customers are the ones who stand to benefit the most from installing solar, because their bills are so high -- because of tiers,” James Barsimantov, principal at EcoShift Consulting, the consultancy that developed the analysis used by the Sierra Club, said in an interview last week. “Low-use customers’ bills aren’t so high because they’re on low tiers.”

There’s more to the argument for tiered rates than that, of course -- they also help spur energy efficiency investment and energy-saving behavior on the part of customers trying to avoid those higher bills, Sierra Club contends. But in a strict economic sense, there’s no direct linkage between the cost of generating electricity and the marginal increase in consumption that occurs over the course of a month -- unlike, say, the very real extra costs of providing peak power during the hottest afternoons of the hottest days of summer.

That makes high tiered pricing an inefficient way to drive efficiency or support solar power, according to Severin Borenstein, UC Berkeley economist and director of the UC Energy Institute.

“When we have increasing block pricing, and the highest tiers are up at 30 to 40 cents a kilowatt-hour, you can really save money installing solar and crowding that out,” he said. “That’s not a reason to have increasing block pricing though -- that’s just a ramification of the policy. I think that it’s basically hiding the subsidies for solar.”

Of course, keeping bills high to help solar economics is hardly a persuasive argument to make to the general public, Shayle Kann, vice president of research for Greentech Media, pointed out. “The solar industry, I think, generally benefits from winning the battle of public opinion on net metering,” he said, “but it’s tougher on tiered rates.”

Monthly Fees That Solar Can’t Spin Backward

That may be why AB 327 opponents have largely focused on the second big change that the bill could introduce to California residential electricity rates: monthly fixed charges. Under AB 327, the California Public Utilities Commission could consider allowing the state’s big three investor-owned utilities to seek permission to charge flat fees of up to $10 per month to every customer, no matter how much power they consume.

While the bill wouldn’t mandate those fees, solar advocates worry that allowing them will lead quickly to seeing them imposed at the state’s big three investor-owned utilities. If that happens, “no matter how energy-efficient you are, or how much solar you have, you’re going to be paying $120 a year to the utility,” Bernadette Del Chiaro, executive director of the California Solar Energy Industries Association (CalSEIA), said in an interview last week.

California utilities, on the other hand, say they need fixed charges to cover the fixed costs of delivering power to residential customers. For example, while Southern California Edison now collects a fixed charge of less than $1 per month from its residential customers, “we have suggested that our fixed cost to serve residential customers is more like $30 a month,” Russ Garwacki, the utility’s director of pricing design and research, said in an interview last week.

While the state’s big utilities have conducted analyses showing that their rate proposals based on AB 327 would keep most customers’ electricity bills at roughly the same level, they haven’t studied the impact on solar economics.

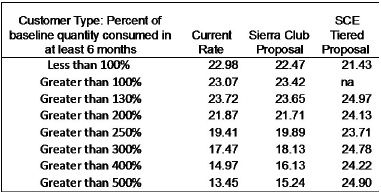

But the Sierra Club analysis, which combined monthly charges and flattened tiers with today’s PV costs and a projected 2 percent annual increase in electricity rates, certainly shows that the long-term payback for rooftop solar suffers as a result. This chart, for example, shows its analysis of how many years it would take to pay off a typical rooftop solar system, under current rate structures, a Sierra Club proposal, and finally, Southern California Edison's recent rate proposal:

“If they move forward and introduce a fixed charge and flatten the tiers, assuming you’re in a higher tier, it definitely significantly reduces that value of solar,” Greentech Media’s Kann said. In fact, it could “go from the customer saving money by having solar, to having the customer pay more money.”

Third-Party Solar Providers Eyeing the Ramifications

Barsimantov noted that the typical homeowner thinking of buying a solar system may not be as mindful of the long-term economic equations involved. But third-party solar providers -- companies such as Sunrun, SolarCity (SCTY), Sungevity, Clean Power Finance, SunEdison (SUNE) and SunPower (SPWR) that have helped create a boom in rooftop solar installations by offering homeowners low-cost solar under long-term contracts -- certainly will be, he said.

Just how important high-tier customers are to these companies’ business models in California is a subject of some debate. In a July conference call with UBS analysts, Bob Kelly, CFO of the publicly traded third-party solar provider SolarCity, responded to a question about how tier changes could affect SolarCity’s business model by saying, “I don’t think it will impact it that much.”

“We play in the second tier given the amounts of power that people use, the amount of savings they can get,” he continued. “It fundamentally comes down to the price of power the customer is paying. […] They can play around with the tiers all they want in California. It’s still going to be a high number.”

That explanation doesn’t ring true to the other solar industry observers we spoke to, who pointed out that homeowners who adopt third-party solar offerings still tend to use more electricity and pay higher bills than the average California consumer.

“With the current tiers, it’s no secret that folks who are in tier 1 and tier 2 don’t tend to have high [rates of] solar adoption,” said Bryan Miller, vice president of public policy at Sunrun and president of The Alliance for Solar Choice (TASC) trade group. “In fact, most of our customers pay more than the average customer, even after solar, because they tend to be larger power consumers.”

As for adding fixed charges to California residential power bills, SolarCity’s Kelly said in his July discussion with UBS, “Obviously any charge to the customer for T&D or distribution or whatever is on this bill increases the price of the bill and makes it more challenging to provide savings for them.”

Now that AB 327 has been amended to include several long-awaited fixes to the state’s net metering policy, companies like SolarCity and Sunrun are being forced to weigh the benefits of bringing certainty to net metering policies against the negative impacts of what might happen to electricity rates as a result, Miller said.

“The thing I would say about AB 327 is, it doesn’t change rates at all,” he said. “Rate reform is going to be decided by the CPUC. All that AB 327 does is give the CPUC some more tools in that process.”

Of course, there’s plenty of concern in the solar industry that California’s big utilities, which are already fighting the expansion of incentives like net metering for customer-owned solar, may be looking to use the rate changes that AB 327 would enable to attack solar via other means.

“There are basically two different ways in which utilities can try to reduce the value of solar, or the amount of money paid to solar,” Greentech’s Kann said. “They could change it through net metering, or they could change it through rates. This is just the other side of the coin.”