The average electric vehicle is now as clean as a conventional car that gets 80 miles per gallon, and produces far less emissions than any gasoline-only car available, according to a recent Union of Concerned Scientists analysis of Environmental Protection Agency data.

For comparison, many hybrids get around 40 miles per gallon.

Plug-in cars aren't always the most environmentally friendly vehicle choice, depending on the location. EVs getting cleaner stems in part from efficiency gains, but mostly from a nationwide electricity mix increasingly infused with renewable power.

“An important difference between EVs and conventional cars is that EVs can get cleaner,” wrote David Reichmuth, senior engineer in clean vehicles, in a blog post for UCS. “It’s difficult to make burning gasoline cleaner, and electricity is trending cleaner over time.”

The UCS analysis assessed location-specific power plant emissions, and how that impacted the electricity used to fuel up an electric car. More and more of the country is now relying on clean energy as a prominent fuel source. Overall, coal accounts for 20 percent less power in the U.S. than it did a decade ago.

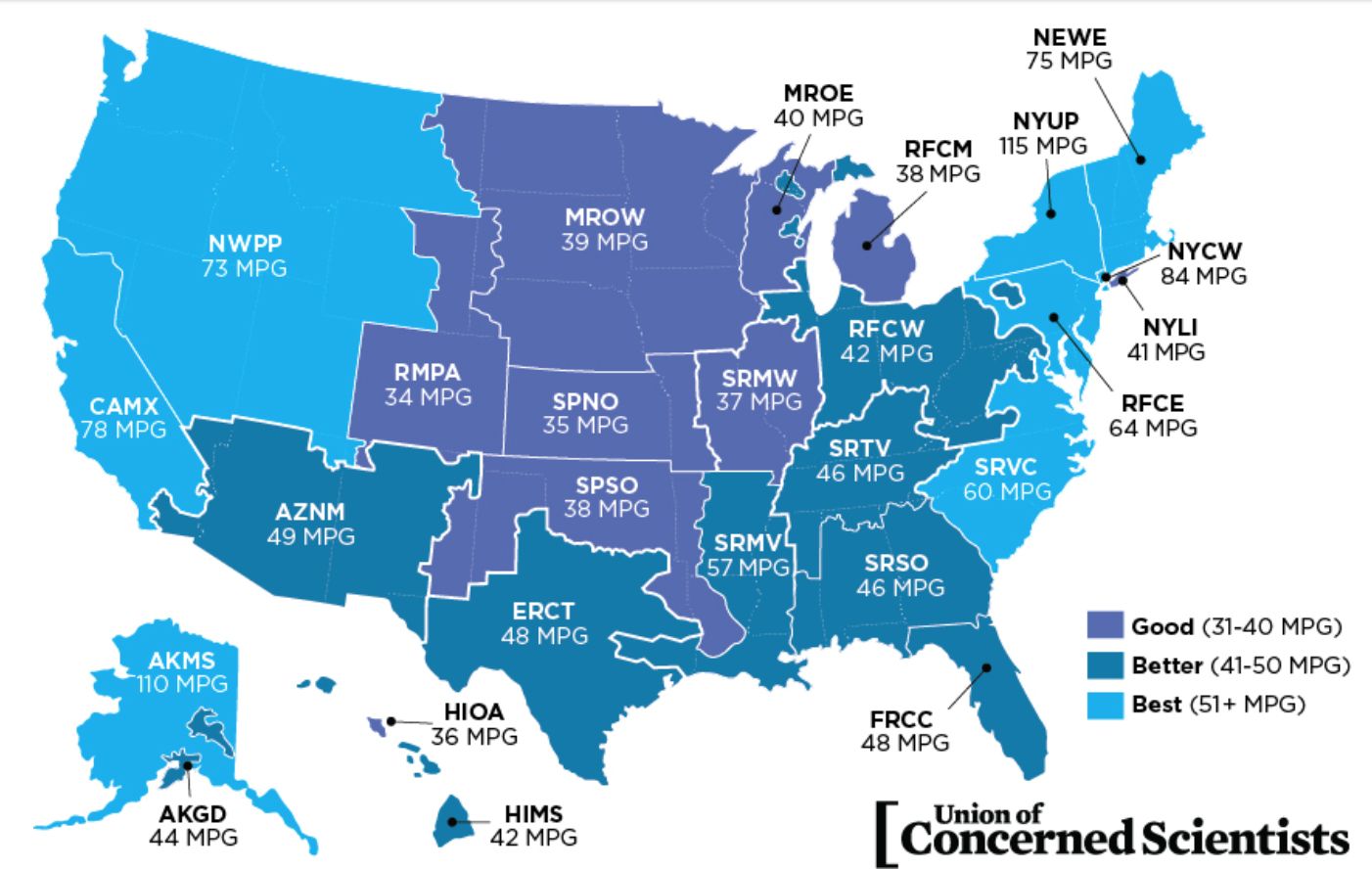

In 2009, the year of UCS’ first analysis, non-hydro renewables accounted for less than 4 percent of total U.S. net generation according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). A map of how clean EVs were across the country reflects that energy mix.

In 2009, the coasts laid claim to the most states with the cleanest-running EVs. States in the middle of the country had electricity that made EVs only as clean as cars that got between 30 and 50 miles per gallon.

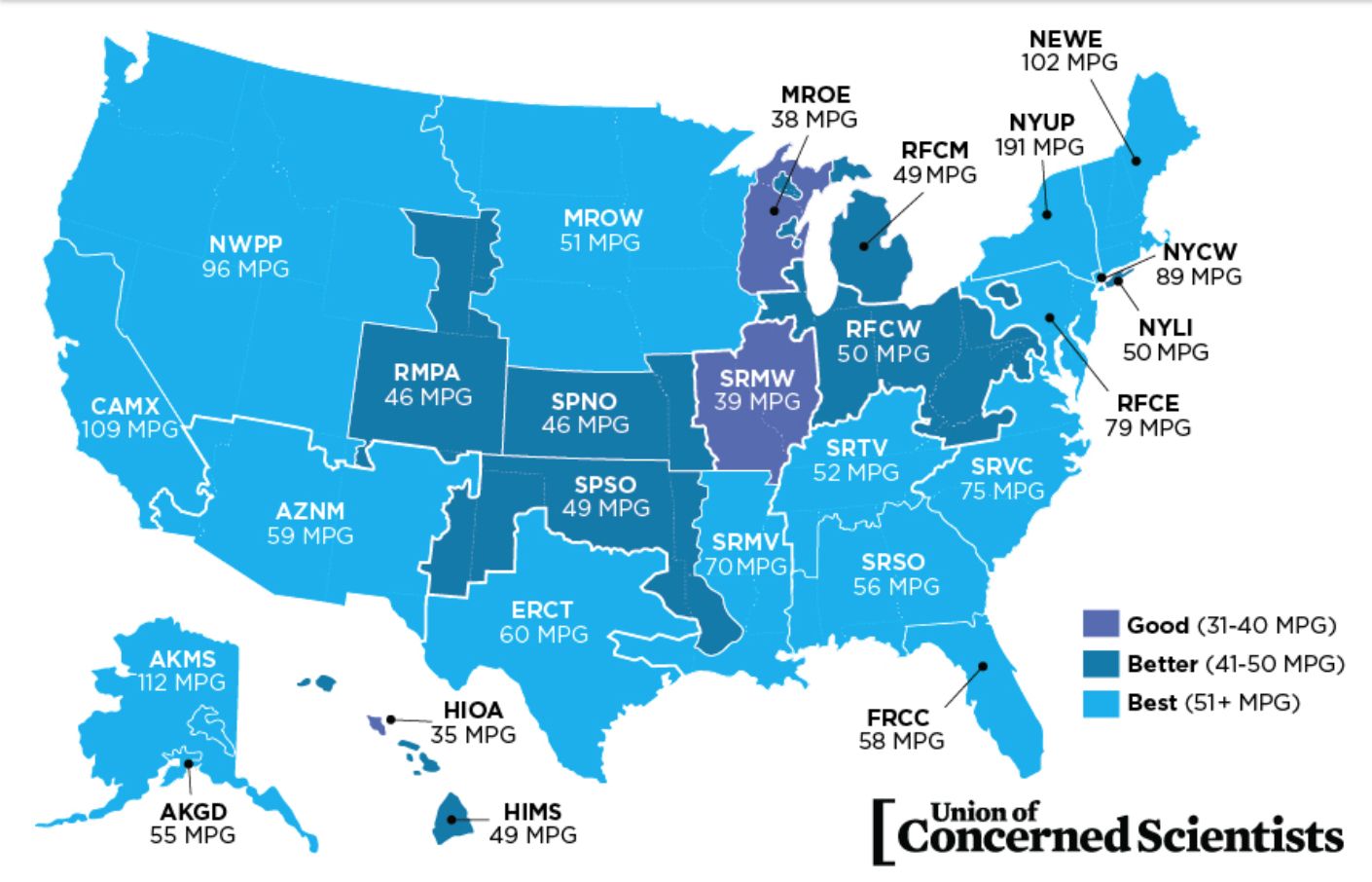

In 2016, the most recent year of data UCS used for its analysis, net generation from clean energy grew to more than 8 percent.

An updated version of UCS’ map shows a much larger swath of the country, representing 75% of all U.S. residents, where the average EV as clean as a car that gets 50 miles per gallon. In the last seven years, every state has shown improvement in the cleanliness of its electric vehicles. Unsurprisingly, the standouts include California and New York -- but also Alaska.

EIA data for 2017 indicates the trend will continue. Non-hydro renewables accounted for about 9.6 percent of generation last year. Hydro remains the dominant renewable power source, but EIA projects wind will soon top hydro generation.

The progress is more marked for high-efficiency electric vehicles. While UCS’ analysis largely addresses comparisons with the average electric vehicle, Reichmuth noted that a new generation of more efficient EVs -- he cites the Prius Prime and the Tesla Model 3, among others -- makes the outlook even more positive for EVs. Using those vehicles, 99 percent of people live in areas where those cars emit less than a car that gets 50 miles per gallon.

And it's not just electric cars that are getting cleaner. Recent EPA data shows that efficiency improvements have also lowered emissions from conventional automobiles in recent years. In 2016, carbon dioxide emissions from new vehicles hit a record low at 359 grams per mile.

At the same time, the Natural Resources Defense Council notes that gains in fuel efficiency have slowed in recent years from an improvement of half a mile per gallon between 2014 and 2015 to 0.1 miles per gallon in the latest EPA assessment.

That chilling comes at an uncertain time. Stricter standards, an area in which California has always led, compelled most improvements in fuel economy. But in an interview with Bloomberg last week, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt indicated he might put the kibosh on those efforts.

“I understand California’s role in this process,” he said. “But California is not the arbiter of these issues.”

If the federal government rids California of its waiver to set its own vehicle standards, manufacturers will likely continue increasing EV investments, but it could slow down improvements for traditional cars.