The biggest headlines for the U.S. wind industry in 2010 held promise and foreboding for 2011.

1. Triumphant 2009 U.S. growth turns dismal.

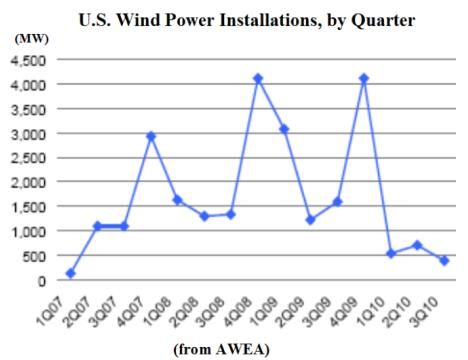

The wind industry’s 10 gigawatts of new installed capacity in 2009 fell off in 2010 as a year of policy uncertainty created by the failure of congressional action prompted angry words from Jeff Immelt, the CEO of leading U.S. wind turbine manufacturer GE. "The rest of the world is moving 10 times faster than we are,” he said. “We have to have an energy policy. This is just stupid, what we have today."

By the end of the first half of 2010, slow U.S. development caused Denise Bode, CEO of the American Wind Industry Association (AWEA), to describe the situation as “dismal.”

Third quarter 2010 projections suggested the industry would finish the year with perhaps 5,000 megawatts of new capacity, about half its 2009 performance, half Europe’s performance and a third of what China will have built in 2010.

2. Offshore wind starts turning around.

Cape Wind, the utility-scale installation proposed for Massachusetts’ Nantucket Sound, won the backing of the Department of Interior after fighting and overcoming every kind of siting and environmental impact objection by opponents ranging from the Hyannis Port Kennedy family to Cape Cod Native American tribes.

The advancement of Cape Wind was a banner triumph in a series of offshore policy clarifications, announced development plans, exploration lease permits, PPA signings and studies showing the enormous economic opportunities of Atlantic Coast and Great Lakes wind. With Europe at nearly 2,500 megawatts of offshore capacity and China’s handful of operational megawatts expanding, it looks like the U.S. may finally have an operating installation by 2015.

3. Advances in transmission: the other good news.

In California, Southern California Edison completed and inaugurated a new 1,500-megawatt capacity line that will deliver wind-generated power to Los Angeles. In doing so, it kicked off a new building boom in the Tehachapi Mountains, one of the state’s windiest regions.

With an estimated 300 gigawatts of potential wind capacity across the U.S. awaiting wires to carry it, the California achievement led a series of advances in transmission building, planning, and policy clarification that will drive development of all renewables.

Google joined a consortium committed to building the Atlantic Offshore Connection, an offshore backbone line to carry 6,000 megawatts to load centers on the Eastern Seaboard.

Wind-rich states in the Midwest and West adopted the Competitive Renewable Energy Zone (CREZ) concept established in Texas to identify where wind and other renewable assets are located and to make certain there is adequate transmission for them.

At year’s end, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved a cost allocation plan for new multi-state transmission that is expected to speed new development.

4. China.

Lost amid the news of 2009’s triumphant U.S. wind capacity growth was the fact that China, for the first time, took over world leadership in new capacity installation. China now has at least two manufacturing companies among the world’s top ten (Sinovel and Goldwind). It is installing both new domestic transmission and new domestic wind capacity at mind-boggling rates.

Both Sinovel and Goldwind are, controversially, also making deals in the U.S. and around the world as world installed capacity moves quickly toward 200 gigawatts, led by emerging markets like Brazil, Mexico, Turkey, and India.

International competition is becoming fierce, but U.S. companies like GE remain in the game, suggesting how effective they could be if, like Chinese and European companies, there was real policy support.

_468_360_80.jpg)

5. Manufacturing takes root.

2010 saw new wind turbine tower, blade and nacelle manufacturing facilities go into service in states like Colorado, Arkansas, Iowa, and Kansas, and announced plans for new facilities in many other states went ahead despite uncertainty. It was a hint of the rebirth in U.S. manufacturing the wind industry could lead in a favorable policy climate because of its preference for sourcing its huge components near where they will be used rather than transporting them.

Wind power’s potential to provide blue-collar work was the basis for a new alliance between the wind industry and the United Steelworkers union. The first thing the new alliance called for was a national Renewable Electricity Standard (RES) because that would give manufacturers and developers the long-term policy certainty they need to build.

6. Integration.

Early in 2010, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) released studies of the U.S. transmission system’s capability to integrate increasing portions of variable renewable energy. The Western Wind and Solar Integration Study (WWSIS) and Eastern Wind Integration and Transmission Study (EWSIS) strongly verified that wind can supply 20 percent to 30 percent of the country’s electricity without any risk to reliability if system operators’ access to available balancing mechanisms is maximized.

7. Bigger turbines.

In 2010, the 2.5-megawatt turbine, with a nameplate capacity adequate to supply power for nearly 500 U.S. homes, became the industry standard. The 845-megawatt Caithness Shepherd’s Flat project, to be the world’s biggest onshore wind farm when it goes online in 2012, will use GE 2.5-megawatt machines.

China’s Goldwind, like GE, is still selling “last year’s model” 1.5-megawatt turbines widely but more and more developers are opting for Goldwind’s 2.5-megawatt nameplate capacity, especially in China.

In Europe, where getting more production out of a single erected turbine is increasingly urgent and manufacturers are turning their attention to the stronger winds offshore, turbines in the 3-megawatt class from companies like ENERCON and Siemens are selling. GE, Goldwind and others are pioneering 4-megawatt machines.

American Superconductor and Clipper Windpower are working on 10-megawatt machines and, this month, Spain’s Gamesa announced it would lead a consortium in the development of a 15-megawatt turbine it says will be tested by around 2015.

_468_360_80.jpg)

8. Coming attractions appear.

The direct drive transmission got more attention in 2010. Startup Boulder Wind Power, helmed by former NREL head wind engineer Sandy Butterfield, opened for business in Colorado, and China’s Goldwind, which has been developing direct drive for some years, entered the world market. Many say direct drive transmissions, with fewer moving parts and a lower-maintenance profile, will soon find a solid niche, and some have even speculated about a complete transition away from standard gearboxes.

LIDAR (laser-based) technology from Natural Power and SODAR (sonar-based) technology from Second Wind both became more common in 2010, sometimes replacing and sometimes complementing traditional anemometer towers, as the accurate measurement of a site’s wind became vital in financing decisions and system operators’ integration practices.

Floating deepwater turbines became a reality in 2010 as Norway’s Statoil put its experience with offshore oil platforms to work and the newly DOE-funded DeepCwind Consortium National Research Program at the University of Maine began methodically developing scale models.

The year also saw important research from Canada further discounting the substantiality of so-called wind turbine syndrome as well as new protections for birds, bats, and radar.

9. Natural gas vs. wind, natural gas & wind.

Newly-tapped natural gas shale reserves kept supplies high, prices low and interest in building gas power plants stirred up. During wind’s 2005-to-2009 boom period, its primary competition for new generation was natural gas. In 2010, as new wind capacity dropped, natural gas took prominence and both consultant Black & Veatch and the DOE’s Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicted big growth in natgas.

Some speculated about wind’s demise, but the Worldwatch Institute, among others, pointed out the crucial partnership between wind and natural gas for integrating higher levels of low-emissions energy into wider U.S. use.

10. Goodbye Renewable Electricity Standard; thank goodness for 1603.

Multiple studies and passionate speeches about the economic and other benefits of wind (and other renewables) did not convince U.S. Senate recalcitrants to institute an RES, and suddenly, on November 3, the Production Tax Credit (PTC), the Investment Tax Credit (ITC), the manufacturing tax credit (48C) and the 1603 Treasury Grant program all looked like potential targets for the newly elected spending-wary Congress.

It was therefore a celebrated, end-of-the-year triumph for the renewable community when the Obama Administration was able to convince the Senate to give the 1603 program, which makes tax credits viable in a recessionary economy, one more year of life.