Elon Musk is a master of gaining media attention. So when he casually released a long white paper on a “fifth mode” of transportation -- the hyperloop -- it was received with intense enthusiasm and skepticism.

The hyperloop is an electric-propulsion pod train system suspended on air cushions in a near-vacuum tube with a pressure equivalent to flying at 150,000 feet (try to say that 10 times fast).

The “train” will in this case consist of as many pods/capsules as needed, with capacity for 28 people per pod. Each passenger pod is fairly small, just wide and tall enough for two seats. The two tubes of the hyperloop (one going each direction) would be suspended on concrete pillars, generally about 20 feet high, thus allowing for the tube to pass over existing roads without disruption, which is not possible for high-speed train systems.

Musk and his team estimated that this method would cost just $20 each way, and that a single hyperloop system between Los Angeles and San Francisco could transport up to 7.4 million people each year.

The total cost to build was estimated at about $6 billion for the passenger-only version. A version that could include cars along with people would cost a little more. The initial design that Musk sketched out was for a route between Los Angeles and San Francisco, projected to take just 35 minutes at a top speed of 760 miles per hour.

The suggested benefits of the hyperloop are many. They include lower cost of construction and operation, faster speeds than high speed trains (HST) and even airplanes, and fewer environmental impacts.

Are these claims accurate? And are we anywhere near actually building a hyperloop?

Many people have been inspired by Musk’s vision of the hyperloop, and at least three companies in the U.S. are now working seriously on the concept. Musk’s own company, SpaceX, is developing a hyperloop pod test track and is hosting a competition for the best pod designs; Hyperloop Technologies has raised significant funding already and is hiring for a ton of open positions; and Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, a virtual company with members spread across the U.S., is focused on building a 30-minute hyperloop between Washington, D.C. and New York.

I’ll look at each of the major claimed benefits of the hyperloop in turn.

Energy efficiency

The original Musk white paper describes the general problem as follows: “Short of figuring out real teleportation, which would of course be awesome (someone please do this), the only option for super fast travel is to build a tube over or under the ground that contains a special environment.”

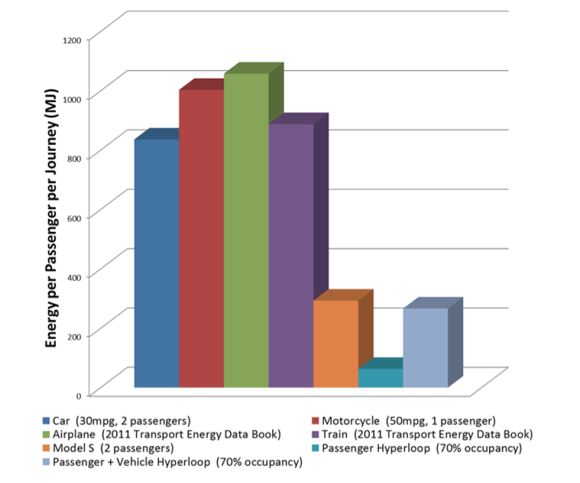

A major advantage of the hyperloop tube concept is its potential for extremely efficient transportation on a large scale. Musk’s white paper suggests that the energy required per seat-mile of travel could be as low as 50 megajoules per journey between San Francisco and Los Angeles, far lower than other possible travel options. The figure below is from the white paper, but no sources or calculations are offered.

FIGURE: Efficiency Comparison Between Various Transportation Modes for Travel Between San Francisco and Los Angeles

Source: SpaceX Hyperloop white paper

We can find support for these figures if we agree that the hyperloop can be powered mostly or entirely by renewable energy. If powered entirely by solar and wind power, the net emissions of the hyperloop are practically zero. We still don't know if it's as efficient as Musk calculated, because a prototype hasn’t even been built yet. We would also need to account for the emissions from constructing components and concrete, etc.

"By placing solar panels on top of the tube, the Hyperloop can generate far in excess of the energy needed to operate,” concludes Musk in his white paper. He calculates that 57 megawatts of solar would fit over the tubes of the hyperloop and would be more than enough to power the entire demand (though it also states elsewhere in the paper that as much as 285 megawatts could fit on the hyperloop; this appears to be a discrepancy in the paper, which is described as an "alpha study," and so is not meant to be a polished final product).

Even if the hyperloop uses coal or natural-gas power, at the expected level of energy efficiency, it may still be more efficient and environmentally friendly than alternatives like high-speed rail or plane travel. This will depend on the actual designs that are built, rather than the white paper’s suggested designs. But again, if constructed hyperloops use solar power, wind power, or other renewable energy to power the hyperloop, the emissions fall to practically zero.

All three companies working in the space have stated their intention to use renewable energy to power their hyperloops, but it’s not clear at this point how concrete those plans are. Rough calculations show that it is not difficult to install enough solar on top of the hyperloop to meet all projected demand, even for busy routes.

If solar power is deemed infeasible (some designs suggested putting the tubes on top of each other, which would reduce the surface area available for solar panels), large land-based wind turbines at 2.5 megawatts to 3 megawatts each would likely be enough to power most routes. Wind power is generally cheaper than solar power, but it faces more permitting hurdles, so perhaps a mix of solar and wind power would be ideal. Batteries and/or grid backup could be used when the intermittent renewables aren’t available.

System costs

A key feature of the hyperloop concept is the ability to construct the entire system in highway medians, which means that existing rights of way can be used for many of the planned routes. This reduces the costs substantially when compared to high-speed rail, which requires a significant amount of new land.

Cost issues have drawn the most flak from critics. Projected costs for a new technologies usually end up being wildly off the mark -- and typically not in a favorable direction.

Daniel Sperling, founding director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis, offered some early criticism of the concept in 2013: “There’s no way the economics on that would ever work out.”

Michael L. Anderson, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, was more detailed in his economic critique, stating his view that it would cost about $1,000 per person for the Los Angeles to San Francisco route, based primarily on far higher land acquisition costs than what Musk estimated.

Design and safety concerns

One can easily criticize every aspect of the hyperloop as untested and speculative because, well, the entire concept is untested and speculative. But such a criticism would be unfair, because every concept starts out as untested and speculative. (Most people in the space industry laughed off Musk's vision of dramatically cutting the cost of space services.)

Time well tell whether the features described above pan out. But one important set of concerns is not discussed at all in the white paper: human factors.

The white paper's pod design will not allow people to stand, walk around or go to the bathroom (indeed, there isn’t a bathroom to go to). While a 35-minute trip wouldn’t seem to require these luxuries, when we consider that traveling on the hyperloop will mean sliding at very high speeds through a confined and windowless tube, there does seem to be the potential for adverse reactions.

Some designs, however, include larger capsules that would allow standing up, walking, and even going to the bathroom. So this is not necessarily a show-stopper.

We’ll also need to see more concrete designs and testing before concerns about the physiological effects of rapid acceleration and banking -- or claustrophobia effects -- can be fully allayed.

Third-party review

At least one third party has completed a detailed analysis of the hyperloop concept: the Suprastudio at UCLA.

This engineering studio takes on one major project each year, using students and volunteers to do a deep dive into aspects of major engineering problems. The Suprastudio partnered with Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, one of the three companies described above, to produce a 158-page white paper.

After the one-year study, it found that the hyperloop concept is sound, with enormous potential. But, of course, many ideas and engineering tasks need to be fleshed out much further.

The white paper includes a comparison of today’s flight time and potential hyperloop travel times for a cross-country trip. It calculates just 2.5 hours for a non-stop hyperloop route versus seven hours for a non-stop flight, which includes the check-in, wait times and baggage claim process that don't apply to hyperloop travel.

Suprastudio also scoped the potential for connecting the nation’s megaregions with a single hyperloop grid, showing the potential for truly transformational change from hyperloop implementation.

So what will the future transportation system look like? My feeling is that we’ll see hyperloop catch on in the U.S. and around the world if it gets past its initial deployment phase in the next few years. Containing costs will be key to that success. If it does catch on, it will supplant many air-travel alternatives.

In the same time period, we may also see a huge increase in driving if autonomous cars catch on. Autonomous cars will be far slower than hyperloop travel, but they will offer far more convenience and personalization, which will for many people outweigh the slower travel time. It will be like having one’s own personal train that can go almost anywhere. Musk wants to be at the forefront of both technology shifts.

***

Tam Hunt is a lawyer and owner of Community Renewable Solutions LLC, a renewable energy project development and policy advocacy firm based in Santa Barbara, California and Hilo, Hawaii. He's also author of the new book, Solar: Why Our Energy Future Is So Bright.