A just-proposed California law would do away with the state’s 33 percent renewables mandate in favor of a coherently procured greentech future. And the plan is backed by renewables advocates.

Assembly Bill 177 (AB 177), authored by Assemblyman V. Manuel Perez (D-56th District), describes a new way for California to approach the procurement of renewables like solar, wind and geothermal, along with energy efficiency (EE) tools like demand response (DR).

“Procurement shall not be limited by any targets established for these resources by statute or regulatory decision,” the bill states. So much for the idea of a new renewable portfolio standard (RPS) establishing a higher goal for renewables when California reaches its 33 percent by 2020 target.

Instead, AB 177 would make it “the policy of the state to require all retail sellers of electricity, including investor-owned electrical corporations and local publicly owned electric utilities, to procure all available cost-effective energy efficiency, demand response, and renewable resources, so as to achieve renewables, reliability, and greenhouse gas emission reduction simultaneously, in the most cost-effective and affordable manner practicable.”

This seems like a new idea but, the bill notes, is “consistent with the loading order adopted by the Energy Commission and the commission which sets forth state policy for preferred resources to meet electrical load needs.”

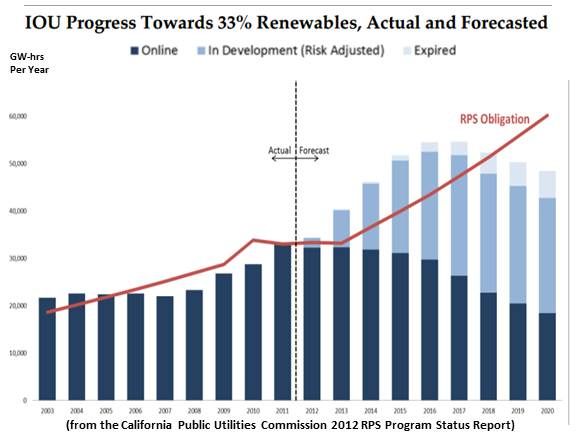

“The California Public Utilities Commission [CPUC] seems to see the 33 percent goal as a ceiling on renewables. It should be a floor,” explained Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies (CEERT) Executive Director V. John White.

CEERT worked on California’s first renewables mandate in 1995, helped develop the 20 percent by 2010 and 33 percent by 2020 mandates, and has been involved in much of California’s climate change legislation. It is now working with Assemblyman Perez on AB 177.

“We have been thinking about how to go beyond 33 percent in a way that reflects what we have learned,” White said. “We have learned that renewables are not a side salad on the greasy fossil fuels burger plate. They are the main course.”

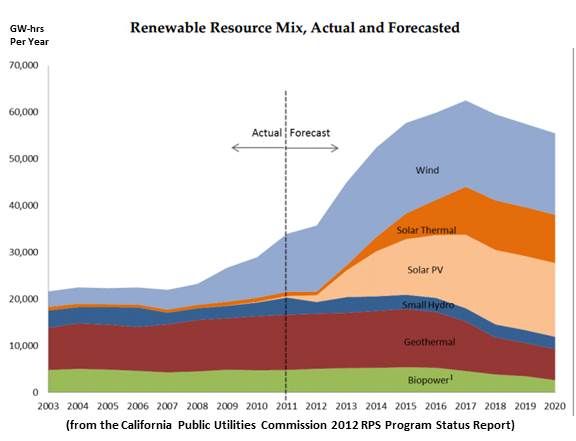

But, White said, “If we are going to go beyond 33 percent, it matters how the resources fit together. We have to plan for that.”

“This bill is going to force a discussion about what California should do to get to its 2050 goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent after it gets to 33 percent renewables, explained David Olsen, one of the five-person Board of Governors that oversees the California Independent System Operator. “The way we are doing renewable energy procurement now is broken and dysfunctional.”

The problem is that procurement proceedings at the CPUC are “siloed,” he explained. There are separate proceedings for long-term procurement, for the RPS and renewables, and for determining resource adequacy. None addresses the state’s emissions reduction policy, efficiency or demand response.

In addition, he added, “The RPS machinery is cumbersome and puts all kinds of constraints on procurement and makes it difficult for utilities.”

Beyond 33 percent, Olsen said, “we don’t need targets if we honor the loading order. It says all cost-effective energy efficiency and demand resource first and all renewables second. The state’s policy is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent by 2050. It is not in keeping with either for a utility to stop procuring at 33 percent. We need a whole lot more renewables.”

AB 177 instructs the PUC to develop a single proceeding, Olsen said, that represents “an integrated, long-term, strategic view for how we are going to meet GHG rules, clean energy, local economic development, and electricity reliability goals, and to solve for those things simultaneously.”

The Perez bill is also consistent with the ISO’s needs, Olsen said, because consistency and clarity about long-term objectives are necessary to manage the grid. “But now, the long-term procurement proceeding makes it look like we should plan for fossil fuels, and the RPS proceeding makes it look like we should plan for renewables, and the local reliability proceeding makes it look like something else. It is difficult to know what transmission will be cost-effective and what will be stranded assets.”

“The RPS had become a green box the utilities checked while they thought about the procurement of natural gas and nuclear power,” White said. “But, suddenly, we have to replace the San Onofre megawatts and we are retiring the old coastal boilers, and the resources we buy have to meet that need.”

California has geothermal, CSP with storage, PV, wind, demand response, and energy efficiency, White noted. “We have a whole symphony of resources, but we need to bring them together based on the long-term policy objective of cutting GHGs 80 percent by 2050. And we need to get both the public and the utilities thinking and planning toward those long term goals.”