The Trump administration on Tuesday introduced a plan for the nation’s coal plants that loosens regulations set out by the previous administration.

Under the Affordable Clean Energy rule, a rework of President Obama’s signature Clean Power Plan (CPP), states will have autonomy to decide how to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from coal plants on a plant-by-plant basis through heat-rate efficiency improvements rather than working to achieve overall emissions cuts. There is no base requirement for states to reduce emissions. The plan also allows power plants to circumvent pollution reviews that accompany facility modifications that the industry says are expensive.

While the CPP’s design compelled clean energy development, Trump’s plan could buoy aging coal infrastructure. Official calculations from the Environmental Protection Agency project the rule will decrease carbon dioxide emissions 1.5 percent below currently projected levels by 2030, but other estimates suggest the rule could increase emissions by at least 12 times that of the existing CPP scenario.

In an impact analysis of the rule, the agency noted that "the proposed rule is expected to increase emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and increase the level of emissions of certain pollutants in the atmosphere that adversely affect human health." The EPA also said the rule would drawdown electricity prices by 0.2 percent to 0.5 percent in 2025.

"As compared to the CPP, we believe that there is going to be very little difference as to how the CPP would have played out versus how this proposed rule would play out if it were to be finalized,” said Bill Wehrum, assistant administrator for the EPA's office of air and radiation, on a call to reporters about the rule.

Since the Obama administration introduced the CPP in 2015, it has faced significant challenges. Twenty-seven states sued over its implementation, and the Supreme Court eventually placed a stay on the rule.

Despite the objections, experts suggest the majority of states are on track to meet the targeted emissions cuts, 32 percent below 2005 levels, by 2030. Today the U.S. is currently at about 28 percent below 2005 levels, according to Jeff Deyette, director of state policy and analysis at the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Climate and Energy program. The Rhodium Group projects that without any regulations on carbon dioxide, emissions would decrease 30 to 39 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

Even many of the states behind the legal challenge, at least nine of the 27 according to 2017 data from the Rhodium Group, will meet their stated CPP goals, helped along by investments in clean energy and natural gas.

“The Clean Power Plan itself was actually never unachievable from the perspective of where the market was actually going,” said Caitlin Marquis, manager of federal and state policy at Advanced Energy Economy.

Despite the national 32 percent target, the CPP was designed to function on a state level. States that cut emissions below the designated targets could trade compliance credits to states that did not achieve their goals. Whether or not states chose to trade would determine how much the plan brought down emissions.

The Rhodium Group analysis found that, with states trading, the CPP would bring emissions down up to 72 million metric tons. Those reductions would reach 91 million to 206 million metric tons if states did not trade. In a world with cheap gas and renewables, much like the modern market, the analysis found that only 12 states would need to significantly alter course to meet the standards.

Rhodium is working on updating its 2017 numbers in response to the Trump rule. John Larsen, a director at Rhodium and the leads of its U.S. power sector and energy systems research, said changes in power markets since the October analysis mean some states are even closer to meeting targets than they were at that time.

“The burden is actually lower than it was before," said Larsen. "None of the states that have to do something would have to radically remake their electric power sectors compared to where they’re currently going; They run their gas more instead of their coal, or they build their wind farms and then they’re done.”

Utilities in Wisconsin, Iowa and Michigan, for instance, have announced commitments to phase down coal or go completely renewable.

Legislation introduced since the analysis indicates that if states opposing the CPP are not making significant progress on clean energy, many are at least grappling with it.

Lawmakers in West Virginia, the state the administration chose to focus on in releasing the new rule, introduced a bill in February that tweaks the state’s net-metering policies. The state has sued over the CPP. In Indiana, current bills in the legislature would create a green jobs training program and require a clean portfolio standard for utilities. That state also sued over the CPP. Nebraska, another state suing over the law, is considering the Wind Friendly Counties Act and the Community Solar Energy Economic Development Act.

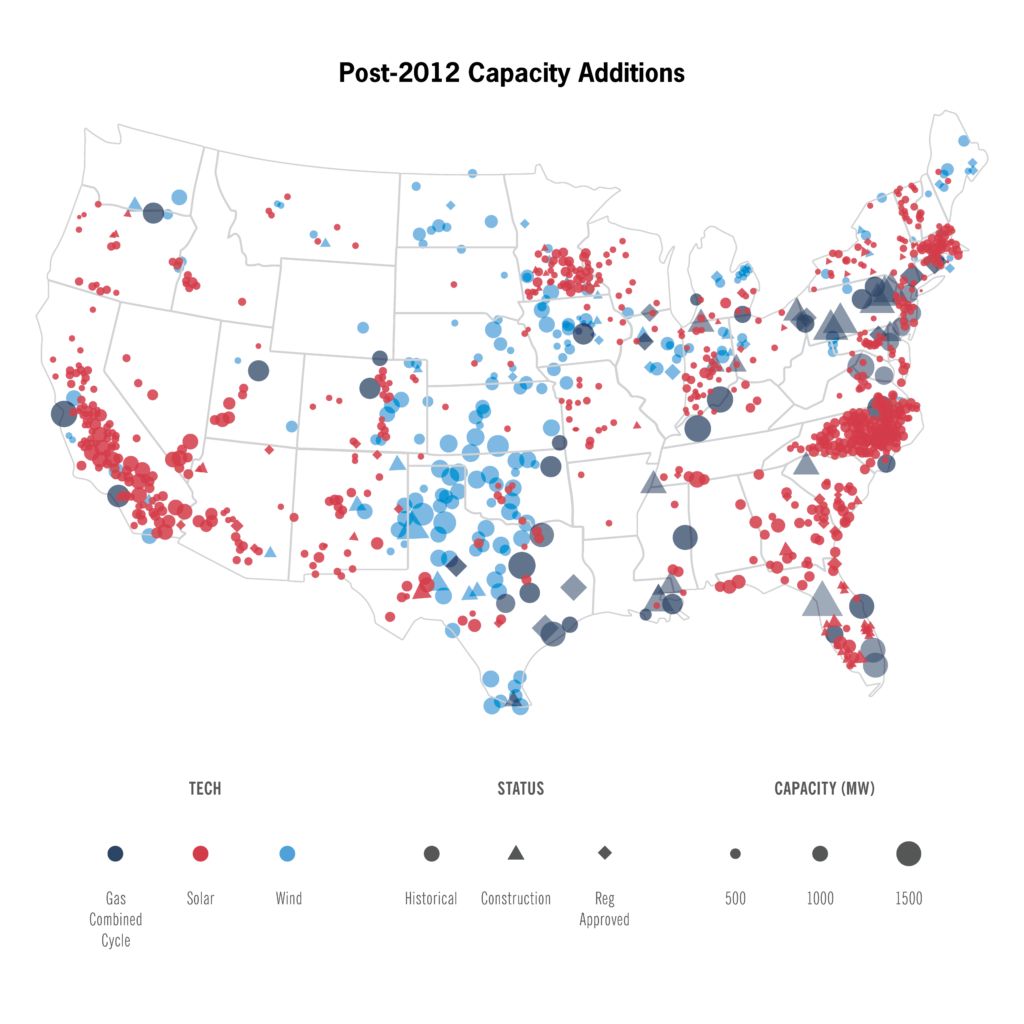

Though some of these laws may not get off the ground, they suggest growing mainstream acceptance of clean energy. Analysis from the Bipartisan Policy Center shows clean energy projects cropping up in states that challenged the rule, such as Texas and North Carolina.

The Bipartisan Policy Center

Experts say the federal policy changes challenge that progress but won’t likely derail it.

“Of course, there are going to be a handful of states that are just going to be dragged along to this clean energy transition,” said Deyette. “But I’d say for the most part, many states are on track for meeting the current CPP.”

Marquis compares the CPP to bumpers on a bowling alley lane. Market forces are already pushing coal retirements and lower emissions, but the CPP added certainty on that course.

“It’s all putting us on this trajectory,” Marquis said. “But we could veer off if these market forces change.”

Though changing the rule removes some certainty, she said utilities, states and corporations are still choosing advanced energy options based on cost and performance.

“Losing [the CPP] is a loss for additional deployment,” Marquis said. “But it’s certainly not going to collapse the market.”

Without the bumpers, more onus falls on market forces such as low wind and solar prices or cheap natural gas to keep states and utilities on a trajectory toward lower emissions.

In some cases, Deyette said the change in pollution review requirements could compel some utilities to keep old coal plants running longer. He points to areas of the country like Appalachia or the Rust Belt, where utilities such as First Energy and Dynegy have supported policy measures to bolster coal.

Other “leadership states,” like those along the West Coast, may not stray from their course at all, according to Deyette. Though he said those states are “doing a service” in creating a clean energy framework for the laggards, the millions of tons of additional carbon dioxide that will result from the rule change does concern him, because the U.S. is already underperforming on climate goals.

Not even the current CPP would have put the U.S. on track to meet the warming target of 1.5 degrees Celsius that the Paris Agreement called for. In addition to pulling out of that international pact, last week the Trump administration proposed rolling back another Obama environmental rule, loosening emissions standards for cars and revoking a waiver that allowed California to more stringently regulate tailpipe emissions.

“We can’t get to where we need to go in terms of emissions reductions based on leadership states alone,” said Deyette. “That’s why an aggressive national policy is so important.”

Under the Affordable Clean Energy rule, states will be required to submit plans to regulate plants three years after the rule is finalized. But with legal challenges likely to delay the rollback, it is unclear whether and when it will be enforced.

As possible challenges play out, experts say the overall energy market will continue to shift.

Like Marquis, Deyette called the CPP a “clear signal” to industry on where the power sector was headed. But he agreed that the corporate, state and utility-led drive toward clean energy and natural gas will continue regardless of the changes.

“Look at the comments of a number of CEOs of major coal dominant utilities like AEP or Duke Energy — it clearly shows that there is momentum; it’s not a matter of if but when there will be comprehensive carbon emission reductions requirements,” Deyette said. “Even in those places where we’re still heavily coal-dependent today, I think the forces are much stronger driving them toward a clean energy future than hanging on to the fossil past they’ve had.”

UPDATE: This story has been updated to reflect comments from the EPA on the final proposed rule, as well as additional comments from Rhodium Group.