It boosts the power output of photovoltaic panels. It heats water. And SunDrum's solar collector is similar to one of the parts in a high-end PC or server.

Hudson, Mass-based SunDrum is raising funds now to go into further prototyping and manufacturing. The firm has devised a liquid-filled heat sink that effectively absorbs the heat that builds up on photovoltaic panels and shuttles it to a water heater in a basement or utility room. The heat sink sits on the underside of a solar panel and is roughly the same size.

Heat sinks – effectively hunks of metal shaped to carry heat from one place to another – are standard equipment in PCs and LED lights. To cool extremely powerful processors, some manufacturers have created fluid-filled sinks that can remove even more heat than standard parts. Last year, IBM came up with a heat sink for a high-end server that passed chilled water (in copper tubes) over chips. Hobbyists meanwhile, sometimes surround components with water or mineral oil to keep components cool.

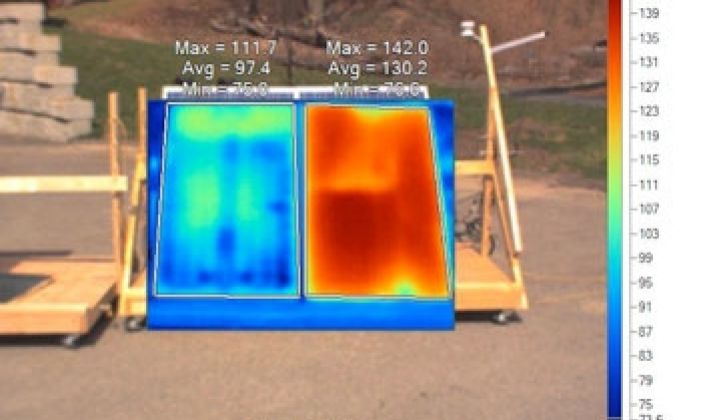

In solar, a heat sink becomes a two-fer, explains CEO Ron Smith, who ran various divisions at Intel before SunDrum. (The chipmaker has in recent years become a finishing school for several greentech execs). Excess heat hurts the efficiency of solar panels and the heat builds as the day goes on. The surface of a standard solar panel in the midday Arizona sun can reach 130 degrees Fahrenheit or more. By cooling them by 20 degrees to 30 degrees Fahrenheit, the panels can perform closer to their rated power. The photo reflects a test conducted by the company.

"We can increase the power output by 6 to 7 percent consistently," he said.

At the same time, the panels generate enough heat to provide a substantial amount of hot water to a building. The additional cost runs about $2.50 per watt for a home installation or $1.50 for a commercial installation.

A host of startups have sprung up recently with the goal of harnessing more of the power of the sun than standard PV panels can. The best solar panels only harvest 23 percent of the sun's energy. By harnessing heat as well, these devices can capture 75 percent of the energy or more beaming toward earth.

Chromasun, founded by former Ausra CEO Peter Le Lievre, makes a device that combines solar cells (for electricity) along with a solar thermal collector that is used to power a chiller-style air conditioner. BrightPhase Energy, meanwhile, has a solar PV/thermal device that also lets in light through a skylight (see Can You Go Cheaper Than First Solar?). Other companies in the combo market include Entech Solar and Cool Energy.

These devices, however, are complete solar systems in their own right. By contrast, SunDrum just makes the device that conducts heat (along with the plastic tubes and services to connect the rooftop system to water tanks in the basement.). The one-fourth-inch thick collector attaches to the back of a conventional PV panel. The plan is to get solar manufacturers and/or their dealer networks to carry it as a complimentary option. SunDrum, thus, won't ideally have to compete against Suntech or other established PV makers to get into the market.

Smith also argues that the way it attaches to the back of the panel also makes it easier in many instances for commercial buildings or apartment complexes to adopt both PV and solar thermal. Rooftops only have so much spare room for solar devices. If there are three or four stories in an apartment building, that may force a choice between putting up a solar thermal absorber or a PV system. Because SunDrum's absorber sits beneath PV panels, it doesn't add to the amount of real estate used.

The collector consists of two sheets of aluminum with input/output ports for the fluid, which is a mixture of distilled water and propylene glycol. The secret sauce lay in the design of the channels inside the heat sink. The fluid does not travel in tubes -- that would reduce the area of contact between the fluid and the aluminum. Instead, it flows through a maze of canals and the fluid touches the aluminum directly. The fluid additionally moves relatively slowly. As it oozes under two or more PV panels, the fluid gathers heat.

The heated fluid then goes to a tank in basement where the heat can be transferred to the water tank. Compared to some combination solar devices, SunDrum's collector can only tolerate low temperature. The fluid can't go past 180 degrees Fahrenheit because the fluid travels from the panel to the basement tanks in plastic tube rather than copper to economize on equipment. But that's warm enough to provide hot water for a home or an apartment building, depending on the number of collectors.

So far, the company has certified compatibility with a variety of solar panels from Evergreen Solar, Sanyo, Sharp, and SunPower, but it will probably work with more. Solar panel frames aren't standard across the industry, but they are somewhat close.

While it seems most appropriate for warm regions, it works in a variety of geographies. SunDrum rigged up a house in Massachusetts with it.