Sooner or later, utility customers end up paying for the costs of smart grid deployments in the form of increases in their electricity rates. But how much return are they getting for those costs?

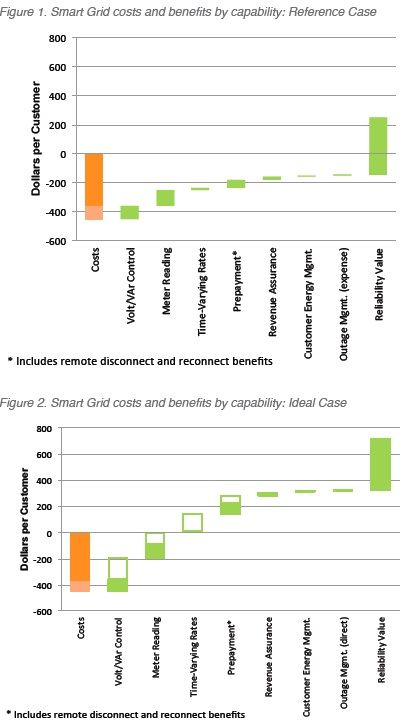

On Tuesday, the Smart Grid Consumer Collaborative (SGCC) released a report meant to answer that question -- and the results are positive. Taking figures from a range of real-world smart grid deployments, the smart grid consumer research group finds that the direct benefits accruing to customers, plus the indirect benefits that come from increased reliability, should add up to a thirteen-year payback of $1.50 for every dollar in costs, or a net benefit of about $247 per customer.

And that’s just the conservative “reference case” that SGCC applies to its roster of benefits made available from smart meter and distribution automation deployments. If those technologies can be optimized to deliver all the benefits they’re capable of, which the report refers to as its “ideal case,” the long-term savings could add up to a thirteen-year ROI of 2.6-to-1, or $713 per customer.

The results -- along with the concomitant greenhouse gas reductions to be achieved by lowering consumption of fossil-fuel-fired electricity -- will now play a part in the SGCC’s push to convince smart-grid skeptics that these investments are not only necessary to upgrade today’s aging grid, but worthwhile to the end users of this grid electricity.

“What is it that consumer and environmental advocates need to be more supportive of [pertaining to] these investments? A lot of us feel, and I feel, that these two groups aren’t as supportive of a smarter grid as they should be,” Patty Durand, SGCC’s executive director, said in a Monday interview. “We set out to find a consultant that could do a good job producing a piece of research that could speak to these two groups at a level they care about.”

Paul Alvarez, president of the Wired Group, turned out to be that consultant, and described the report’s methods in Monday’s interview. Costs per customer were derived from a host of Department of Energy smart grid stimulus-grant-funded projects, with capital costs that added up to an average of $292 per customer for smart meter deployments, and $64 for distribution automation, with an additional annual operations cost of about 4 percent of the original investment.

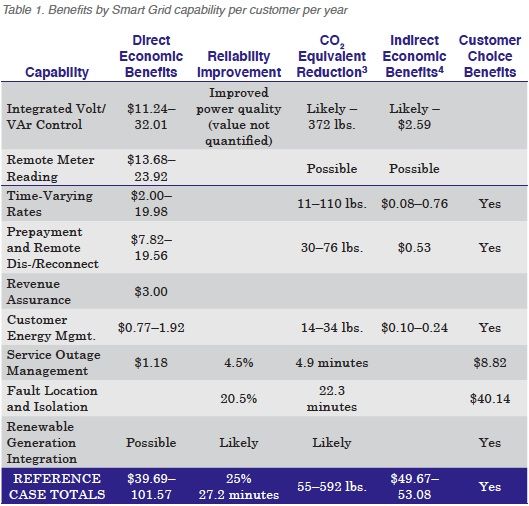

Benefits were collected from lists of discrete cost reduction and efficiency improvement categories that apply across both sectors on a per-year basis, as shown below.

Direct benefits equate to “everything other than reliability,” Alvarez explained. “They could come from multiple places -- operations and maintenance cost reductions, energy efficiency, capacity reductions, conservation efforts on behalf of customers -- but they are all quantifiable in terms of dollars on a customer’s bill.”

The indirect benefits, on the other hand, come from increased grid reliability, and are calculated on industry-standard benchmarks relating to how much power outages cost the economy in terms of lost productivity. While some of those costs are borne by utility ratepayers, the vast majority won’t appear on bills, he said. Still, they're a key benefit, as detailed smart grid deployment cases like the one recently introduced by AEP Ohio make clear.

As for separating the reference case from the ideal case, Alvarez described the former as representing today’s utility landscape, where smart grid deployments are still in their first stages of optimization. “The ideal case is more a measure of what’s reasonably achievable,” he said, but it’s still grounded in real-world measures of best-of-breed type deployments, and thus “well-grounded in reality,” he said.

What can the smart grid industry learn from these metrics? Certainly the difference between the report’s reference and ideal cases underscores the pressure to optimize the way today’s smart grid systems are managed, to squeeze out as much value as possible. We’ve been covering efforts like these, from putting smart meter data to use for broader utility priorities, to the challenges of delivering volt/VAR efficiencies across the grid at large.

At the same time, reports like this also remind us of how important it will be for utilities to make their case for smart grid in the public arena. GTM Research’s newly released grid edge report calls this ”progress visibility,” in terms of tracking costs and benefits both within the industry, and perhaps more importantly, for utility regulators and customers.

It’s important to remember that most consumers tend to harbor both a mistrust of their utility and a fear that the smart grid costs them money without delivering any commensurate benefit. The fact that most utility customers don’t have a choice about who they buy their electricity from makes it pretty much impossible for them to vote with their pocketbooks -- and puts consumer advocates in the role of fighting against unfair rate increases on the public's behalf.

Certainly we’ve seen utility regulators in states including Illinois, Maryland, California and Ohio echo this skepticism, in the form of rules that require utilities to measure and report on just how smart meters, distribution automation and broader grid deployments are delivering customer benefits.

The challenge here is that today’s costs yield future benefits that roll out slowly, as utilities update their rate cases, Durand noted. That’s why the report’s payback period is measured in units of thirteen years: three years for the deployment to be completed and ten more years of operation to prove its value.

In the meantime, utilities, environmental groups and ratepayer advocates need to get involved in asking themselves, not just what costs they’re being asked to bear today, but what future benefits they can expect to receive -- and, of course, what might happen to the grid if nothing is done.