Utilities have installed more than 50 million smart meters across the United States, but most of those meters still aren’t sharing meaningful energy data with their customers. And that failure to make use of technology is leaving billions of dollars of energy-efficiency savings unrealized -- and opening the door to third-party alternatives that could threaten the utility-customer bond.

That’s the unfortunate picture painted by a report released Wednesday by the More Than Smart nonprofit group and the Mission:Data industry group. Only a few states -- California, New York, Illinois and Texas -- have created a working mass-market model to require customer access to their home or business energy usage data, according to the report.

“Obviously, the digital side of grid modernization is as critical as the physical side of things,” Michael Murray, More Than Smart’s chief technology strategist, said in an interview this week. “California has dealt with some of these issues. But there are other states now, most notably New York, that are considering how to make meter data available, under what circumstances, and who pays for this infrastructure.”

Outside the aforementioned states, however, smart meter data-sharing has languished, he said. That’s too bad, because multiple studies show that giving customers access to energy-usage data in some recognizable form can lead to efficiency improvements of between 6 percent and 18 percent.

Meanwhile, non-utility players are bringing in large numbers of people who care about energy, and they’d love to have a standard set of utility data to work with, Murray said. But that’s been a very slow process.

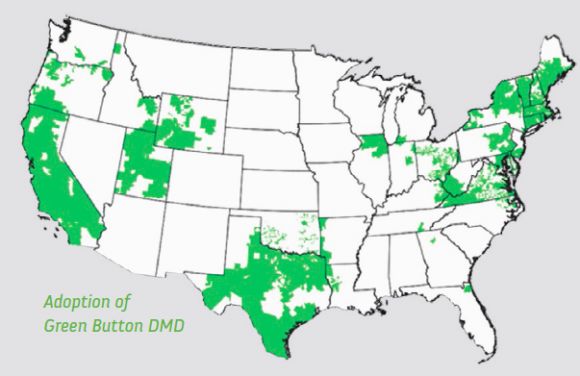

Green Button, the energy data standardization effort launched by the White House in 2011, has led to some broad adoption across the country. It’s also built up a library of some 236 applications, built by dozens of startups, but also featuring software interfaces for some bigger energy industry players.

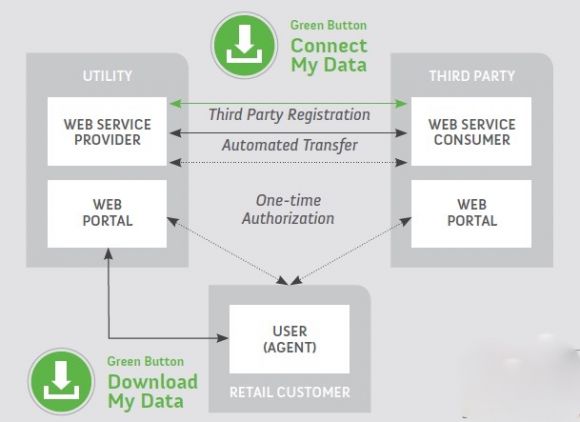

Green Button has gotten even better in California, where big investor-owned utilities have released support for Green Button Connect My Data -- a version of smart meter data-sharing that allows third parties to consistently download utility data once a customer has given them permission.

Every other Green Button implementation is based on the older "Download My Data,” which requires customers to go back and download their data every time they want an update, Murray noted. That’s not a very user-friendly prospect in a world where virtually every whim can be met by downloading a new iPhone app.

The other problem with Green Button data is that it’s at least a day old, he said. That’s because it’s been collected from smart meter networks, run through meter data management for error-checking and verification, and put into a data repository for access.

Far fewer utilities have made the real-time data from smart-meter home area networks (HANs) available to customers. Most of the smart meters in North America include a ZigBee radio capable of putting out second-by-second readings, but the few states that have opened them up have seen low uptake and technical problems.

Even so, there are some school districts and commercial property owners getting real-time data out of smart meter HANs in California. Larger customers of retail energy services providers in more deregulated markets like Texas and Illinois are also pushing for real-time data access.

On the residential side of things, New York’s Reforming the Energy Vision (REV) process has put customer data access on its to-do list, and Illinois has mandated data-sharing for its utilities under state law. Notably, both these states are still in the early stages of their smart meter rollouts (Illinois) or just starting to debate the first multimillion-meter utility rate cases (New York).

Utilities and regulators often get caught up on issues of data privacy and security, which can discourage them from taking a stance on the matter, Murray said: “Utility commissions don’t want to be caught with their pants down, authorizing something that leads to a privacy breach.”

Without a utility infrastructure for getting this data in standard forms, however, third-party distributed energy companies will be forced to do it themselves. Wednesday’s report quotes Eric Carlson, SolarCity’s grid services director, on how the solar installer decided to install its own metering gear in California homes, after finding the process of connecting with utility smart meters too time-consuming and error-ridden. Now SolarCity has its own broadband connections and on-site metering and control systems, which it plans to put to use for grid services in the future.

The longer utilities take to make their data available, the more they’ll see this kind of workaround, Murray suggested. Wednesday's report highlights the use of "web-scraping" techniques by efficiency and energy services companies, which pull data from every recognizable utility source -- online bill statements, tariff structure filings, etc., as a potential disintermediation threat for utilities down the road.

“If you want controlled access to information, you do need to have a sanctioned method, where third parties are registered with the regulator and the utility. If you fail to acknowledge this, as everybody is apt to do, then there are going to be problems.”

Here are the recommendations laid out by the report:

- Commissions should require utilities to provide the best available energy-usage data to customers (and their authorized third parties) in a standardized electronic format as part of basic utility service.

- Tariffs should be published in standardized, machine-readable forms so that software applications can quickly and accurately calculate expected costs.

- Customer bills should also be available to customers (and authorized third parties) in standardized electronic format.