There's been an uptick in U.S. microgrid activity as developers discover new ways to monetize value streams outside of remote and island communities. According to GTM Research's recently published North American Microgrid 2015 report, approximately 50 percent of the current domestic microgrid operational capacity of 1.2 gigawatts has been commissioned since the start of 2013.

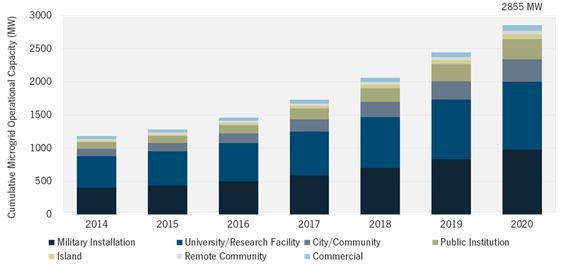

And although we expect microgrid capacity to exceed 2.8 gigawatts by 2020, there are still significant market and regulatory barriers which need to be addressed.

FIGURE: U.S. Microgrid Capacity Forecast by End-User Type, Base Case

Source: North American Microgrids 2015

Top microgrid barriers: All regulatory

The roles, rights and responsibilities of electric utilities are protected by a long-established set of regulations that has not yet adapted to a changing power supply landscape. While some efforts do support microgrid development, most legacy regulation provides support for building out large interconnected power networks rather than pockets of high-reliability, flexible systems. This has prevented third-party-owned and -operated microgrids from functioning as small-scale utilities.

In April 2014, the California Public Utilities Commission issued a report recommending that state utility commissions take a more active approach to defining the role of microgrid owners and operators in the distribution network. Other agencies including the state of Maryland and NYSERDA (PDF) have also published extensive documents outlining their perspectives on utility and third-party microgrid ownership structures, as well as applicable financing models.

Despite these ongoing efforts, no regulatory concept for commercial multi-user microgrids has yet emerged. The following list summarizes the most pressing regulatory barriers to wider development of large microgrids.

- Utility franchise rights: Designed to govern the use of public space by third parties, utility franchise rights substantially limit the ability of third-party providers to realize larger projects that may be economically more attractive. Since selling power to third parties via new distribution lines infringes on these rights, non-utility entities may face significant legal battles that may lead to considerable litigation costs.

- Threat of being subject to public utility regulation: Any entity that sells energy or power and whose equipment crosses a public street is technically defined as an electric corporation and therefore falls under the traditional utility regulation and ratemaking authority of the state’s public utility commission. The prospect of being treated as a traditional utility, where billing, rates, and quality of series are all regulated, adds significant cost and risk, further reducing a project’s economic viability.

- Insufficient definition of microgrid interconnection procedures: In the current regulatory environment, microgrid interconnection requirements and associated costs and benefits are generally negotiated on a project-by-project basis and often differ in each state. For example, a hybrid mix of resources may deem a microgrid unable to receive a net-metered rate for power or energy export. On the technical side, while IEEE 1547.4 establishes interconnection guidelines for DER islanded systems, rules governing microgrid grid-support functions (e.g., volt/VAR support) remain insufficiently defined to allow microgrids to support utility operations without significant customization. Navigating this complex and unclear legal framework is often time-consuming and expensive for a developer.

And that’s not all. Unresolved issues around distribution network costs (like standby charges), project financing, and performance metrics are being examined by several public utility commissions. While these barriers do create significant uncertainty and project risk, it is important to recognize that regulatory progress is being made and that the market is expected to significantly grow beyond its current state with or without major reform.

The utility opportunity

On the subject of growth, while such regulatory barriers do pose a more significant challenge to private-sector projects, several developers have identified the utility space as a major microgrid opportunity.

There has been much talk about utility modernization efforts, whether that be to address system reliability, distribution congestion, variable generation intermittency, or other factors. Much of this has been folded under the umbrella definition of larger-scale microgrid projects in states like California, Illinois, Maryland and New York.

In May, Energizing Co. and asset investor Stonepeak Partners unveiled a $250 million finance facility focused on North American utility microgrid and grid modernization developments, leveraging private-public investment models and targeting projects of 100 megawatts in capacity and over $50 million in costs. Energizing Co. has also partnered with Leidos to provide engineering services and economic analysis.

Building on Exelon’s existing expertise in its distributed-generation and wires business, the deregulated utility is partnering with project developer Anbaric to tie in experience with developing large-scale high-voltage DC lines. The partnership plans to develop large-scale microgrid projects in the 30-megawatt to 200-megawatt range at several New York sites including utilities, municipals, and the C&I space.

FIGURE: Large-Scale Microgrid Projects

Source: Microgrids Presentation to DOE Electricity Advisory Committee, June 2015

Ultimately, such mega-projects may redefine the entire microgrid concept. ComEd’s proposed HB 3328 bill to invest up to $300 million in six microgrid pilot projects includes aspects of healthcare, homeland security, transportation and water services -- much of which goes beyond typical microgrid concepts oriented to serve critical infrastructure or remote communities.

GTM Research’s North American Microgrid 2015 report finds that while 49 percent of U.S. microgrid projects tend to be under 1 megawatt of generation capacity, much of the overall capacity is actually attributed to larger-scale projects.

***

Omar Saadeh is a senior grid analyst with GTM Research and lead author of the report North American Microgrid 2015.