Panasonic is laying the groundwork for a massive networked deployment of lithium-ion batteries in solar-equipped homes and businesses to solve Japan’s post-Fukushima energy crisis -- and it’s looking to California and other U.S. markets for the business models to make this distributed energy system work.

That’s how Hiroshi Hanafusa, head of Panasonic’s Energy Solutions Center, described the company’s LiEDO platform, first announced to the Japanese press last year, but unmentioned in U.S. news reports to date. LiEDO combines the Japanese electronics giant’s advanced batteries and energy management systems in solar-equipped buildings with a cloud-based, networked IT infrastructure, Hanafusa said at Wednesday’s Cleantech Forum in San Francisco.

That networked IT platform will both optimize each battery to extend its effective lifespan, and serve to aggregate their collective capacity for multiple energy purposes, he said. That could include storing solar PV-generated power on-site for emergency backup power and overnight use, as well as for peak shaving, demand response and other grid-aligned uses, he said.

In other words, Panasonic is “building a platform to make energy services to use electricity stored in these batteries,” he said. LiEDO is a compound coinage combining “Li” for lithium-ion and “Edo,” the name used for Japan’s capital city of Tokyo before 1868, he explained. The intent is to create a modern, sustainable city infrastructure that can achieve the low carbon emissions of Japan’s pre-industrial-age capital.

“We will start the LiEDO business next year,” Hanafusa told me in an interview after his presentation. Early versions of it are already being introduced in the Fujisawa Sustainable Smart Town project, he added. That's one of many Japanese "smart city" projects seeking to integrate solar PV, energy storage, smart grid and energy management systems to help the country manage the energy crisis it has faced since the 2011 Fukushima nuclear power plant meltdown and subsequent shutdown of its nuclear reactor fleet.

At the same time, “I’m focusing on not only Japan, but also the United States,” he said. In fact, in terms of models for driving the growth of distributed solar-battery systems, “The first market I am looking at is California,” where a mandate to add 1.3 gigawatts of energy storage to the grid by 2020 is pushing the state to create innovative regulatory constructs and business models to meet that goal.

“I am looking for young talent to create new energy services, using lithium-ion batteries, like Tesla,” he said. As has been widely reported, Tesla Motors is planning to build what it's calling a Giga factory that will add a huge new source of batteries for grid-scale storage, as well as its electric vehicle growth plans, and is working with SolarCity on its plans to bring battery-backed solar to homes and businesses in California and other states.

Panasonic, which supplies Tesla with the battery cells for EVs, is rumored to be a likely supplier for Tesla’s Giga factory as well. While Hanafusa wouldn’t state definitively whether Panasonic would be the battery cell supplier for the Giga factory, he did say that it was, “in my opinion, I guess, a high possibility.”

Networked storage for a grid crisis: A market opportunity

Japan has been in an ongoing energy crisis since the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that devastated its northeast coast and caused the Fukushima disaster. With all but two of its 54 nuclear power plants shut down since then, Japan has become reliant on imported oil, coal and natural gas to cover its electricity needs, even as it has imposed severe emergency measures to reduce power use during its peak summer months.

But the same power crisis has led to a boom in renewable energy, and a renewed emphasis on finding ways to integrate that energy into the grid. A lucrative solar feed-in tariff introduced in 2012 more than tripled Japan’s solar PV market from 2012 to 2013. To help integrate this solar power into the grid, the Japanese government last year created a $300 million grant program to support large-scale battery deployments, with three projects worth a combined 82 megawatt-hours announced last year.

At the same time, small-scale distributed energy storage has also gotten a boost in Japan in the form of a government program that helps cover roughly 30 percent of the cost of systems, Hiroaki Murase, manager at Japan’s Itochu Corp., said at Wednesday’s event. That’s supported the deployment of battery systems in about 15,000 homes across the country, he said -- but “what’s missing is how we connect this storage together, and how we control [the connected devices].”

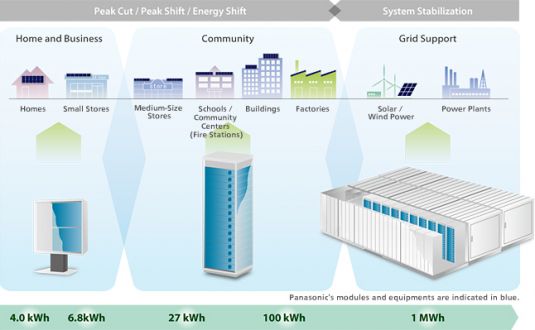

Panasonic’s Smart Energy Storage System is the key building block for its distributed energy plans. Built on battery modules using the cylindrical 18650 cells used in laptops and in Tesla’s battery packs, it’s connected to a battery management unit that coordinates the unit as a whole, and integrates with its home energy management system. It's also meant to scale up to support larger-scale commercial buildings and emergency services like fire stations and hospitals, and can go as large as megawatt scale for larger grid purposes.

But as part of smart city projects like Fujisawa, "We are planning a huge number of battery projects -- small batteries, big numbers," he said. One of the main goals of Japan's smart city projects is to provide most, if not all, of their own power from a combination of on-site renewable generation, energy management, demand response technologies and energy storage. Panasonic and partners like Hitachi, Toshiba, Fuji Electric, General Electric and Accenture at work on these projects are tasked with both providing the services needed at individual buildings, such as emergency backup, and linking them into a mutually supporting "community energy storage" network.

Putting out lithium-ion battery systems at this scale requires careful management from a provider like Panasonic, starting with the basics of safety and reliability. “If you connect the battery with the internet, you can easily control the battery safety,” he said -- a critical consideration for lithium-ion batteries that need careful thermal management to avoid overheating and catching ablaze. At the same time, “I need connections in order to use lithium-ion batteries to the end of life,” he said, to manage their charging and discharging to balance their day-to-day economic value against their long-term capacity and effectiveness.

Eventually, “All batteries we sell should be connected to LiEDO, all over the world,” he said. That concept could eventually include portable batteries connected by wireless networks as well, though that remains just a vision rather than a product right now, he noted.

In Japan’s case, a push to deregulate the country’s electricity sector by 2016 could allow competition in both generation and retail electricity services, providing Japanese players the opportunity to learn from U.S. markets that have already undergone this transition. At the same time, the United States could find itself taking advantage of Japan’s accelerated push of distributed energy technologies into its own market.

Just how LiEDO may find its way into U.S. markets, Hanafusa declined to say at this time. Panasonic is considering go-to-market models that include managing its battery systems as a grid resource, as well as turning them over to other parties taking on that role, he said. But as a hardware company, “we have little time to make business models,” he said, adding that the right “business model is very important.”