The state of Vermont might have solved the problem of solar's 'soft costs' -- as well as provided an impetus for increased solar penetration with a re-vamped feed-in tariff.

Solar pricing in the U.S. is driven by materials costs, as it is everywhere. But the states in the U.S. possess an inconsistent, time-consuming, and costly permitting process, often lumped in as the 'soft costs' of a solar installation. That's why the dollar-per-watt cost of solar in the U.S. is significantly higher than in Germany.

A DOE report from last year claims that inconsistencies in permitting can cost consumers up to $2,500 on a 5-kilowatt rooftop solar system. Solar financier SunRun has said that the wasted money from permitting inefficiencies "looks like a $1 billion tax on solar over the next five years." The cost stems from the time spent by installers in getting the building, zoning, and fire department permits, waiting for inspection and utilities, dealing with changes -- and losing customers in the process. The report adds that Germany has a 40 percent installation price advantage over the United States.

Vermont has shown that the solar permitting beast can be tamed.

Last year, Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin signed the Vermont Energy Act of 2011 (H.56). The law provided for net metered solar power in Vermont, as well as a pioneering permitting process for small solar systems (less than 5 kilowatts) that is a model for reducing the "soft costs" of residential solar.

Now the program is being expanded.

Act 125, in effect this summer, doubles the size of projects allowed under the registration program from 5 kilowatts to 10 kilowatts, opening it up to larger residential and modest commercial-sized roofs.

While the registration and permitting process confronts interconnection issues, the state has also expanded its feed-in tariff program, which addresses the procurement aspect of solar.

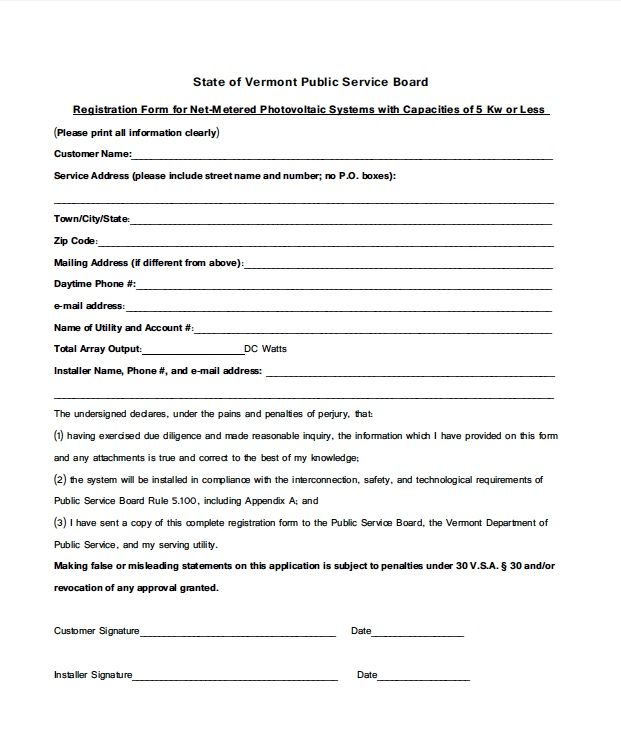

Statewide, solar installations now have a simple and consistent permitting process that can get solar deployments approved in ten days. The new registration form covers system components, configuration, and compliance with interconnection requirements.

Prior to the new law, before beginning a project, a solar applicant would need to receive a permit or Certificate of Public Good (CPG) from the state’s Public Service Board, a quasi-judicial agency that oversees electric power companies and energy projects. When determining whether to grant the CPG for a specific project, the Board would weigh whether the project met site-specific environmental criteria and factors such as need, reliability, and economic benefit. After the application was filed, there was a 30-day comment period, and contested projects were resolved through a public process, beginning with a public hearing.

Now, Vermont's utilities have 10 days to raise any interconnection issues, otherwise, the CPG is granted and the project can go forward.

The cry for an improved permitting process in the U.S. has been put forth by SolarTech, Vote Solar, and other organizations and firms. The DOE SunShot program is looking to get solar to $1.00 per watt installed. It can't happen without a well-thought out permitting process.

Here's the simple one-page registration form:

Doug Payne, the Executive Director of SolarTech, has called this "the sort of 'Micro-Policy' innovation critical to driving up to $1.00 per watt of red-tape out of the marketplace in the next few years."

SunRun's Ethan Sprague said that since solar is new, permitting entities are subjecting 100 percent of system applications to a high degree of scrutiny, when only a few need to be looked at. He said, "It should be more like installing an appliance than re-wiring a house." About Vermont, Sprague said, "What's unique and significant about Vermont's program is the uniformity. They took state-level action, which demonstrates to other states that local permitting reform with the same standards across all jurisdictions is possible."

Vermont has a population of about 630,000 -- so the scale of the state's residential solar deployments is in the hundreds of rooftops as opposed to the tens of thousands of rooftops in California, Arizona, Nevada, or New Jersey, but it is a step in the right direction.

The other policy shift in the Vermont solar market is a 122-megawatt feed-in tariff which comes with a bit of help from the Clean Coalition, a foundation-sponsored distributed solar advocacy group headed by Craig Lewis. The group promotes what they refer to as a "Clean Program," which addresses solar procurement with a feed-in tariff and improved interconnection and permitting policy in the spirit of what was done in Vermont.

Lewis said, "Interconnection is as big a barrier to clean energy as the procurement process." The Clean Coalition also hopes to shift the less-than-graceful term "feed-in tariff" to the only slightly improved "Clean Program." 'Clean' stands for 'clean local energy available now.'

In Vermont, The Clean Coalition focused on removing permitting barriers and expanding the scale of the incentive program. The Vermont incentive program (FIT program, CLEAN program, whatever) has "an interesting feature" in Lewis' words -- if a project provides "locational benefits," it does not count against the 122-megawatt program cap. Lewis defined "locational benefits" as "providing power generation near the load." That would include most urban locations -- places where the energy generated is not subject to large line-loss, the necessity of new transmission, or increasing congestion.

In addition to Vermont, The Clean Coalition was also involved with the recent initiation of a feed-in tariff / Clean Program in Palo Alto, California which Lewis cited as a good example of how to streamline the procurement and interconnection bottleneck. The local micro-policy appears to be catching on. The 10-megawatt Los Angeles LADWP program went live this month with its first pilot and Long Island, New York's LIPA (Long Island Power Authority) starts its own program in July.

Vermont installed 5.2 megawatts of solar in 2011, and looks to install 9 megawatts in 2012 and 16 megawatts in 2013, according to GTM Research.