First Solar (NASDAQ: FSLR) just announced deals for the sale of 50 megawatts of its cadmium telluride (CdTe) thin-film modules to Indian developers Kiran Energy Solar Power Pvt. Ltd. and Mahindra Solar One Pvt. Ltd. for side-by-side 20-megawatt and 30-megawatt projects in the state of Rajasthan.

First Solar’s India strategy “includes establishing a deep local presence,” CEO James Hughes recently said. India is “a very real opportunity.” The company’s impressive average module manufacturing cost of $0.70 to $0.72 per watt, its 12.7 percent efficient modules, and its proven bankability, Hughes believes, are competitive advantages in India.

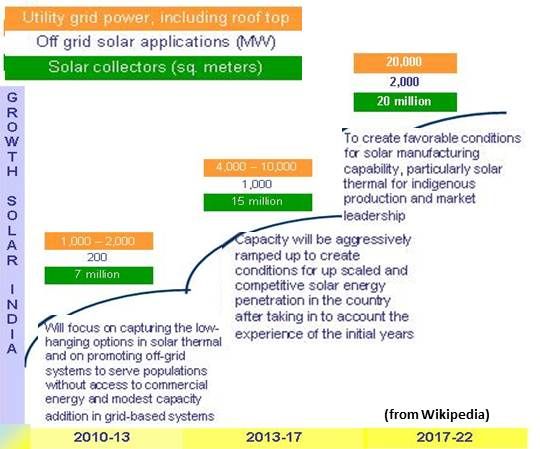

India’s Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM), aimed at the addition of 20,000 megawatts of solar capacity by 2022 through a renewable auction mechanism, closed this year. In addition, several Indian states, notably Gujurat, have solar feed-in tariff programs.

With an energy deficit and infrastructure that led to the world’s worst blackout, India’s turn to solar caused a stampede of capacity building by Indian module manufacturers and a stampede to India by international solar manufacturers, builders and financiers seeking a piece of the action.

“There is roughly 1050 megawatts of cumulative capacity now installed in India,” explained GTM Solar Market Analyst Scott Burger. “Of that, roughly 670 megawatts came from the Gujarat policy and the remaining portion from the National Solar Mission and then a mix of other, smaller policies.”

Burger identified First Solar activity in India that included JNNSM deals with Fonroche Energie Group (twenty megawatts), NVR Infrastructure (two megawatts), Azure Power (35 megawatts), and Green Infra (25 megawatts). The two newest projects fall under the JNNSM. 2011 deals with Reliance Power (NSE:RPOWER) (100 megawatts) and ACME Tele Power Ltd (fifteen megawatts) fall under Gujarat’s feed-in tariff policy.

India solar experts point out a market distortion that favors First Solar.

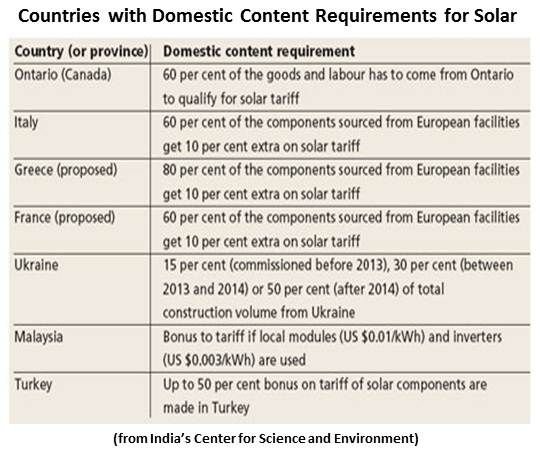

When the JNNSM law was written in 2009, there was a strong domestic content requirement (DCR) for silicon panel-based solar projects but thin-film solar was not on the India policymakers’ radar.

As a result, Burger noted, First Solar is probably the largest module supplier to the Indian market. “We expect to win 20 percent of the market this year and on a go-forward basis,” Hughes has said.

But, Burger said, "there has been uncertainty as of late.” Both Rajasthan state and the JNNSM delayed new offerings. “While I am sure India is committed, the financials of solar are tough to navigate right now,” Burger said. And “the question of a local content law rule for thin film certainly has something to do with the uncertainty.”

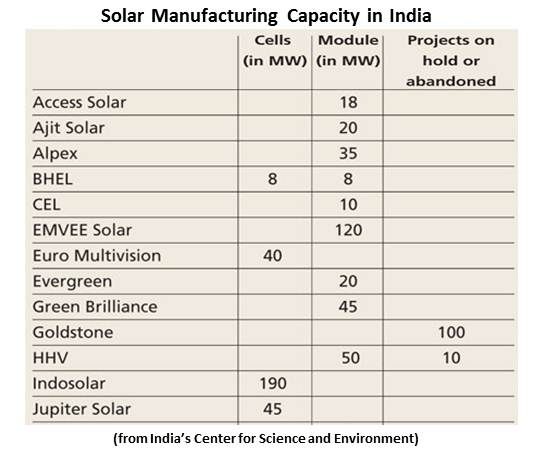

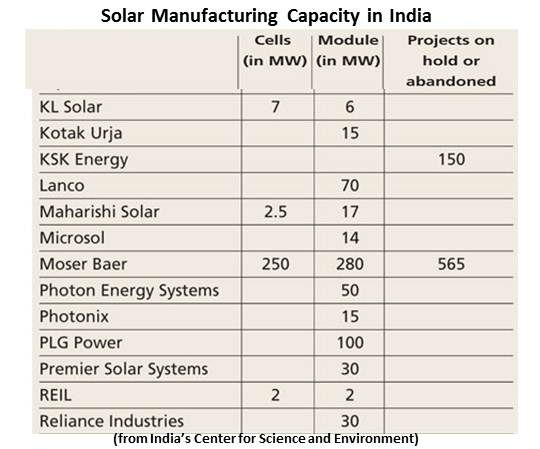

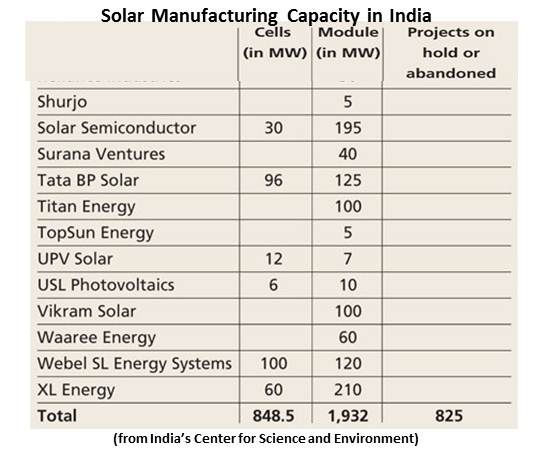

The absence of a thin film DCR was partially responsible for the failure of many Indian entrepreneurs who stampeded to build silicon-based panel manufacturing capability. The other part of their failure was in their price structure.

Competing with low-cost Chinese panel makers supported by the Chinese government has been as challenging for India’s manufacturers as it has been for the U.S. and EU manufacturers who have clamored for tariffs.

First Solar’s advantage in India was a U.S. Export-Import Bank low-cost loan program for international businesses that buy U.S. products. At least $305 million in U.S. Ex-Im Bank loans went to Indian solar projects since 2010 that used First Solar’s thin film.

First Solar is “a visible, bankable brand,” Burger said, but “they are also benefiting from U.S. Export-Import Bank financing.” While India’s solar industry faces 15 percent interest rates from its domestic banks, Ex-Im Bank interest rates for developers who use First Solar’s thin film panels is as low as 3 percent to 4 percent.

Burger and most India solar watchers expect the government to announce some form of a thin film DCR along with the next, 3-gigawatt JNNSM phase. Neither Hughes nor Burger expects this to spell the end of First Solar’s India success.

“We continue to maintain a close working relationship with Ex-Im,” Hughes said, “which plays an important role by providing financing in challenging markets like India.”

That financing will drive module sales, Hughes believes. It might be risky for the company to pursue a market with a new rule directed specifically at excluding them, Hughes acknowledged.

But “a domestic content requirement would likely manifest itself in the public sector programs,” Hughes explained. “We actually believe the private self-generation market is the source of a great deal of the opportunity.” Further, he added, “if the kind of visible demand that we expect develops in that market, that is likely a market where we would look to put manufacturing in place. And so obviously, at that point any such policies would actually be an advantage.”

According to knowledgeable sources in India, Burger said, the country could “move from to a market driven by the National Solar Mission and the Gujurat feed-in tariff to a market driven by renewable portfolio obligations. But I think it will be well beyond 2013 when solar is cost competitive on an unsubsidized basis.”

On the other hand, he said, other factors, like energy security, could drive demand. “First Solar is “looking at India in the longer term. The population is set to explode and they are starting to need a lot of power.” And, Burger added, “there are policies outside the National Solar Mission that may not have domestic content requirements that First Solar could do very well in.”