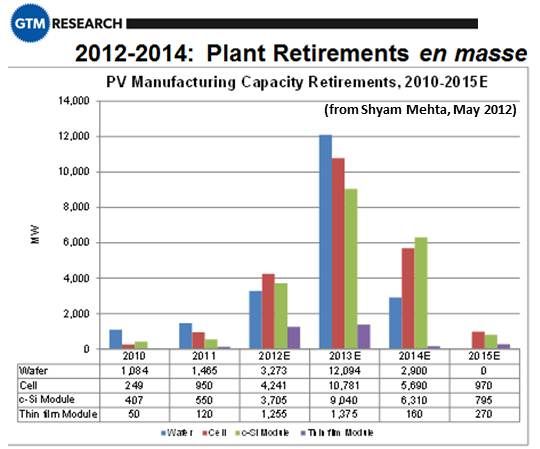

A recent panel of solar CEOs predicted that 2011’s approximately 1,500 solar module manufacturers will have been Darwinized to as few as 100 by 2016.

SOLON Corporation has turned toward innovation for survival. “We are prepared to deal with whatever we need to deal with to play in the market,” explained SOLON Director of Research and Development Bill Richardson.

SOLON SE, the Berlin-based parent company, Richardson said, began as a residential rooftop solar system kit provider, evolved into module manufacturing and then became an engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) provider. It built the world’s first utility-scale solar installation, a twelve-megawatt project. Established as a subsidiary of the now bankrupt SOLON SE, the U.S. company was part of the bankruptcy settlement in which UAE-based cell maker Microsol, took over SOLON SE assets earlier this year.

“Nothing changes for us,” Richardson said. “We are building SOLquick units, doing really fast installs on flat roofs, and looking five years ahead at system storage.”

“We were one of the first to get out of module manufacturing,” added Director of Marketing Patricia Browne. Even before the bankruptcy, “we realized we needed to adapt to the market changes and figure out how to survive.”

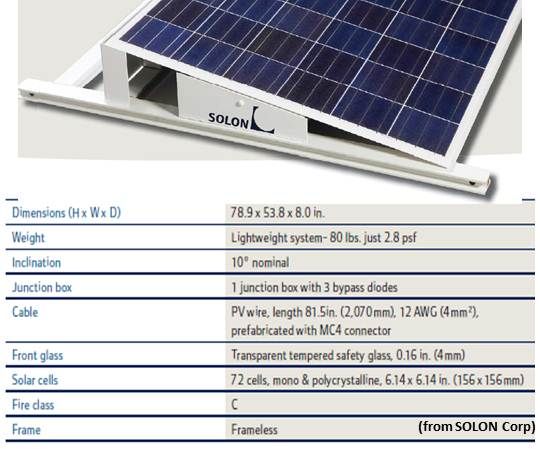

Instead of making modules, she said, “which are essentially commodities, we wanted to add value to the installation market. SOLquick is an integrated laminate and racking system. The traditional approach is having a module and a rack, and then clamping them together. We assemble a frameless module and a wood composite rack, all in one, at our factory in Tucson, and ship out a rooftop system, pre-assembled.”

SOLON Corp. is composed, Richardson said, of a product group and a systems group. The former makes and markets SOLquick and the latter is an EPC.

“Our strength in the U.S. has always been as an EPC provider,” Browne said. “We’ve partnered with PG&E (NYSE:PCG), TEP, and Duke Energy (NYSE:DUK) and we have built nearly 100 megawatts in the U.S.”

Sales and revenue numbers are held private, Richardson said. “But what we can say,” Browne offered as a metric, “is that we are hiring.” The firm currently employs 75 people, the majority at the Tucson facility, and is looking to fill fifteen to twenty positions in sales, construction and technical R&D positions. “And we just recently brought on five to ten [more].”

While proceeding with development in the midsize ten-to-50-megawatt-project space, SOLON is also moving ahead on two innovation efforts: SOLquick, aimed at the near term, and at the SMRT (storage management research and testing) Site, aimed at the longer term.

SOLquick, Richardson said, “is geared for large commercial rooftops, 100 kilowatts and up to as big as a rooftop gets. That’s where it shines. The bigger it gets, the better it is.” It is, he explained, “a frameless laminate, a traditional module without the aluminum frame, which you adhere to a non-metallic substructure made from Fibrex, a wood polymer with a PVC coating.”

“Andersen extrudes the racking pieces and we assemble them in our Tucson factory where we used to manufacture modules,” Browne added.

Because the firm is emphasizing the SOLquick brand, it does not make public which module brands they use. “We can use SOLON laminates, but we have the flexibility to use any laminate we internally qualify that meets our standards,” Richardson said. “The quality and robustness of this is never at issue. BEW just came out with a third-party report on this product, independently assessing it, and said that the due diligence we put into it is far above the general due diligence and testing that is standard in the industry.”

“SOLquick comes with the industry standard 25-year performance, ten-year product warranty for modules,” Browne said, “but we apply it to the entire system.”

Traditional racking manufacturers argue that the unidentified module to which an installer is committed by choosing SOLquick is a disadvantage.

“Our Renusol CS60 is compatible with almost all 60-cell and some 72-cell modules currently in the markets,” Renusol America CEO Bart Leusink told GTM. That “allows for a broader adoption, without limiting the user or installer.”

As part of the University of Arizona’s Solar Zone, built to test solar technologies, SOLON built a 1.6-megawatt, ground-mounted installation with SOLON-made panels on its own single axis-trackers two years ago. Now, in partnership with inverter maker SMA (ETR: S92), Tucson Electric Power (TEP), and the University, the firm is readying SMRT, a five-year field test of storage technologies.

“When we built it, we designed in the ability to have this storage test site that we are now putting into place,” Richardson said. “We are commissioning the first storage technology next month, a lithium-ion battery from SAFT (EPA:SAFT).”

The undertaking will cover a range of technologies, Richardson said. The next test will be an above-ground compressed air energy storage prototype developed by the university. “After that, he said, “the university has a flow battery they are going to bring in.”

SOLON’s intent, Richardson said, is “to get good at integrating different types of storage, because we are going to need different types of solutions for different customers.”

There aren't many in the renewables industries who would take issue with SOLON's long-term interest in storage. The question is whether their integrated rack and module system will get them to the long term.