In the race to grab a piece of the huge untapped wave energy market, Eco Wave Power founder David Leb believes he has a technology that can beat his more than 100 competitors by making the ideal compromise.

In the harsh ocean environment, Leb said, the best waves impose the most on a wave energy system’s cost and reliability. “The challenge,” he explained, “is to find the Golden Middle between producing the maximum amount of kilowatts, while still ensuring the reliability and the long life span of the system.” The unforgiving ocean environment has set back some of Leb's more advanced competitors like Wavebob, Pelamis and Ocean Power Technologies.

Israel-based Eco Wave Power’s technology has just passed an initial phase of prototype testing at the Hydro Mechanic Institute of Kiev. It will take on the major real-world challenge of the Black Sea within the next few weeks.

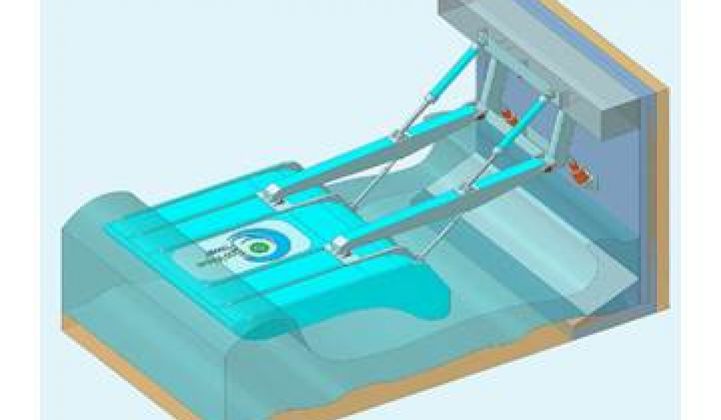

The device consists of a floater affixed by an armature containing a hydraulic cylinder and a generator at the other end of the armature that is affixed to a structure at or near the shore.

The floater absorbs the waves’ energy and moves the armature. The movement of the armature drives the pressurized fluid in the hydraulic cylinder. That movement of the fluid drives the generator, which generates electricity.

The device is engineered to hit Leb’s Golden Middle in four ways.

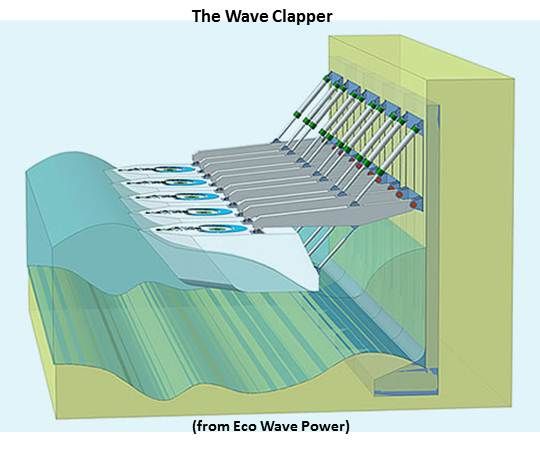

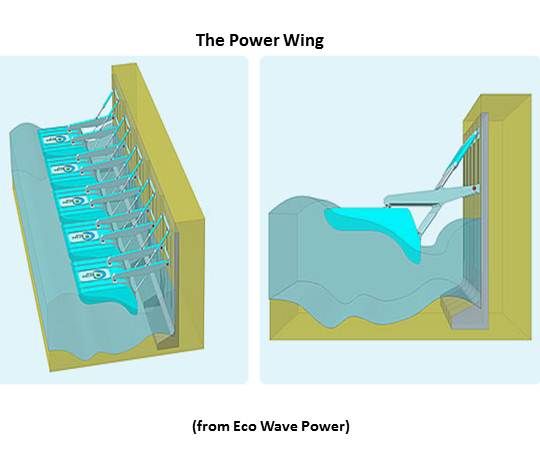

Two models, the Wave Clapper and the Power Wing, are to be tested in the Black Sea. Neither is a conventional cylinder, square or sphere, and both are uniquely shaped to capture as much of a wave’s force as possible and “generate power both at change of water level and from an incident flow.”

Both models have the same volume, Leb said, but are not the same size. The choice of models will be made according to the nature of the waves in the region.

Each of the prototypes ready for testing has a five-kilowatt power generation capability, Leb said. He plans to scale the device up to a 100-kilowatt size for the commercial market and expects to be able to deploy up to ten, in arrays of up to one megawatt.

The device is adjustable to local wave and weather conditions in a variety of other ways. It has different “storm protection mechanisms,” and the floaters can be lifted out of the water or submerged. A “float orientation” turns the device’s front edge to the most productive angle with the wave front. Its surface is protected against corrosion and mechanisms are designed to protect it from wave forces and regulate the movement of the arm that contains the hydraulic cylinder.

One of the key features of the Eco Wave Power device, Leb said, is a control system that can manage the device remotely. It will analyze data about the generator’s consumption of electricity in real time from a “frequency converter” and manage “hydraulic accumulators” capable of increasing or decreasing “the intake of energy.” Its sensors will also, Leb said, allow remote monitoring and response to extreme weather or sea conditions.

Leb said his device will come in at a cost per kilowatt-hour that is below solar, wind or coal, but he has only built prototypes at this juncture, so he cannot have anything but theoretical projections and he chose not to provide any specific numbers. He made a credible case for certain cost advantages his device would have if and when it goes commercial.

Much of the cost of installation and maintenance associated with most wave energy devices, Leb said, would be eliminated because the bulk of the Eco Wave Power device, almost 90 percent, would be installed onto onshore and near-shore existing structures. Only 10 percent to 12 percent of the device, the float and the armature, would be in the ocean.

This also potentially eliminates the high costs of materials that other devices need to protect them from the deep ocean environment, Leb added, as well as the high costs of transmission infrastructure built far out into the ocean.

Although he provided no figures on costs of the prototype’s production and had none, of course, on real-world output, “the return on investment,” Leb insisted, “will be within three to five years.”

Leb said Eco Wave Power is privately funded, partially with his own money, and has no need of further funding. He plans to have a full-scale prototype in the next nine to twelve months and to take the final product to the marketplace shortly thereafter.

Perhaps his optimism is based on a market that he described as “huge, huge, huge” in nations like “the UK, Spain, Portugal and Thailand.” He also said he has already had interest from major hydropower and oil companies. Whatever it is based on, Leb’s optimism is undisguised. “We’re in this to make green energy,” he said very seriously, “but we’re also in it to make green money.”