Utilities are starting to capture the value of the data coming from the edges of their distribution grids. But they’ll need to transform their approach to keep up with the flood of data to come.

Greentech Media’s Grid Edge Innovation Summit 2019 kicked off Tuesday with a series of keynote panels and presentations on this common theme. As with past Grid Edge events, the two-day conference in San Diego is a showcase for the latest technology and policy approaches to manage the interface between the world of utility distribution grid operations and planning, and the distributed energy resources (DERs) like rooftop solar, behind-the-meter batteries and plug-in electric vehicles that are disrupting it.

Much of Tuesday morning’s discussion centered on the utility pilot projects and initiatives that are bridging this gulf, such as Chicago utility Com Ed’s microgrid projects, Ohio utility AEP’s work on the state’s PowerForward initative, or Arizona utility APS’s plans to marry hundreds of megawatts of solar and energy storage. (Watch the sessions on demand here).

Shay Bahramirad, ComEd’s vice president of engineering and smart grid, discussed the utility’s Bronzeville microgrid project, now being expanded via third-party contracts after a multi-year back-and-forth with state lawmakers and regulators. In April, the microgrid ran its first “simulated islanding” test to prove it can support the roughly 700 customers networked to its mix of on-site generation and grid controls, ranging from elderly fixed-income residents to Chicago’s police and fire department headquarters.

Bahramirad highlighted some of ComEd’s technological innovations for the Bronzeville project, such as its synchrophasor-informed “master controller” platform to coordinate multiple microgrids to provide capacity, flexibility and other valuable qualities when the grid is up and running — not just when there’s a blackout.

This “microgrid cluster” approach may be a more workable one than attempting to orchestrate DERs at the scale of the utility distribution grid, given the limitations of utility distribution management systems to respond quickly enough to mitigate power quality or stability problems that can arise on the edges of a DER-rich grid.

At the same time, the Bronzeville project has drawn ComEd into novel collaborations with the local community to ensure that the microgrid is serving their needs, not just the utility’s, she said. “That was completely new to us, moving away from thinking only about a microgrid, to thinking about what the future of that neighborhood could look like.”

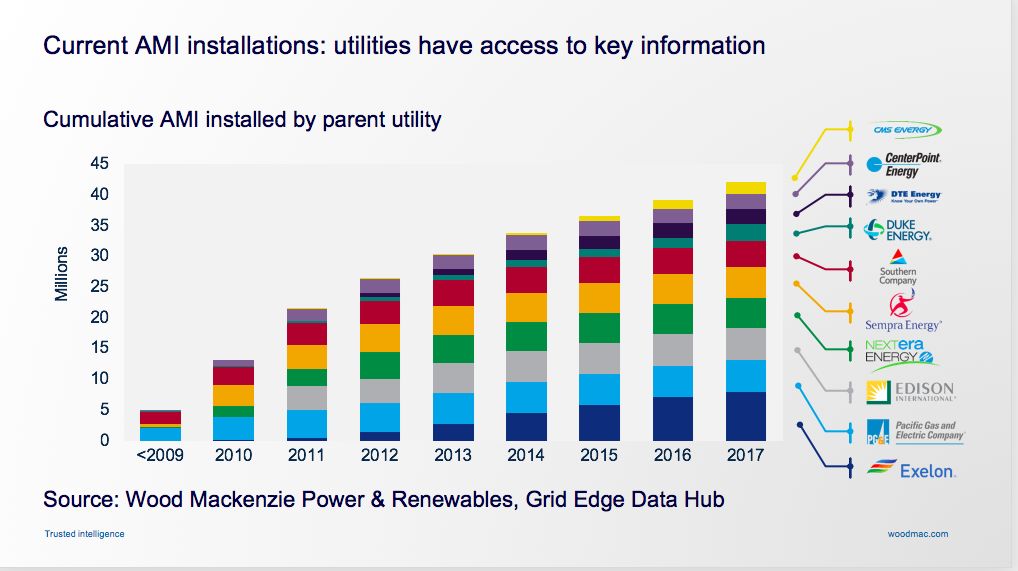

A similar back-and-forth is taking place between utilities and their customers over access to the data coming from the 80 million-and-counting smart meters now deployed in the United States. The latest generation of smart meters is capable of delivering fine-grained data on energy usage, as well as informing utility distribution grid operations, Tim Weidenbach, senior vice president of customer operations for Landis+Gyr North America, noted during Tuesday’s keynote panel.

Ram Sastry, AEP’s vice president of infrastructure and business continuity, noted how the utility’s smart meter deployments are now yielding fruit. AEP Ohio’s Silver Spring Networks (now Itron) smart meters and associated distribution automation (DA) devices and sensors are foundational to more recent energy storage and electric vehicle charging projects, for example. And in Oklahoma, AEP is testing a technology that will detect anomalies in energy usage at the homes of elderly customers, with the aim of alerting their relatives of any changes that may indicate medical emergencies, he said.

At the same time, customers aren’t yet able to fully access the data coming from these utility investments, according to Devin Hampton, vice president of corporate development at UtilityAPI. The Oakland, Calif.-based startup standardizes data exchanges between utilities and their customers, ranging from simple interval energy usage data delivered through the Green Button Connect standard, to more outcome-oriented transactions like solar and energy storage interconnections.

“A good analogy is, when you go to an ATM machine and you pull money out, you don’t care how the banks are talking to each other, you just want your money,” he said. In terms of this analogy, utility-by-utility Green Button Connect implementations still lack the standardization necessary to make one utility’s data conform to another’s model, or visa versa, he said.

Utilities in DER-rich states like Hawaii, California and Arizona are facing the first wave of behind-the-meter data to manage. But in the next half-decade or so, utilities across the country will face the challenge of integrating tens of millions of DERs, ranging from residential smart thermostats to commercial-industrial combined heat and power (CHP) systems, as well as solar and plug-in EVs.

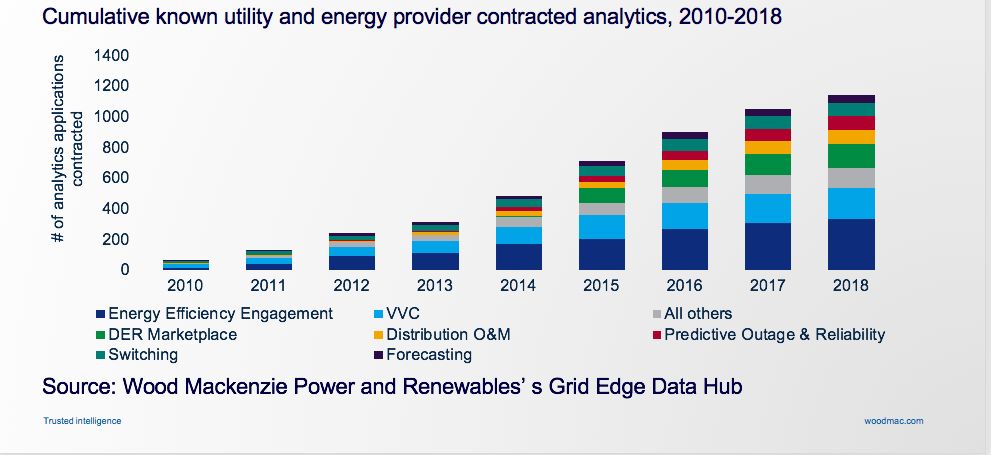

U.S. utilities and energy providers have radically increased their analytics spending over the past decade, as Ben Kellison, grid edge director for Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables, noted in his Tuesday keynote presentation.

But for the most part, the utility approach to undertaking these big analytics projects hasn’t changed from decades past, he said. Utilities will define a decade-long lifecycle roadmap, buy and customize a software platform for the job, undergo a long and arduous data collection and cleaning effort, and then develop the data and processes necessary to support projects, often one at a time.

This ponderous process is poorly suited to keep up with the rapid pace of growth and change in consumer technologies.

To keep pace, utilities will need to reorganize their digital initiatives around foundational data architectures that are also extensible over time, and be willing to review and adjust their ongoing work and investment plans on a quarterly basis, rather than years in, Kellison said.

“When we look at digitalization, I like to think of it less as a physical capability, or a technology, and more as an institutional competency,” he said.

Utilities will need to build their own technology teams, to avoid depending on outside technology providers who lack the understanding or commitment to the utility’s needs, Kellison suggested.