Northern Ohio is coal country. These days, that’s a problem.

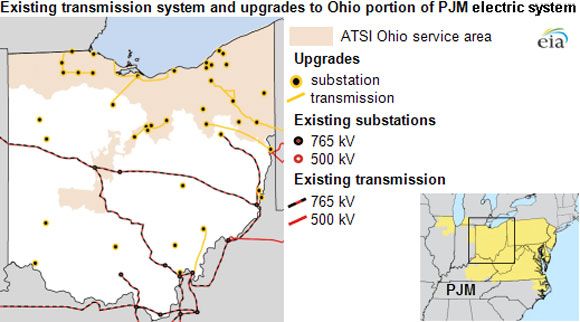

In 2012, 1,400 megawatts of coal-fired power plants were slated to retire in the American Transmission System Inc. (ATSI) load zone in Ohio, a part of the PJM Interconnection.

The generating assets made up nearly 13 percent of generating capacity in ATSI, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. FirstEnergy will retire another 885 megawatts of coal in the region in 2015, bringing the total drop in capacity to 21 percent.

The lack of capacity in coming years drove up prices in PJM’s capacity auction in 2012, so PJM responded with a solution: transmission. One year and hundreds of millions of dollars later, the regional clearing price was back in line with other PJM regions.

Ohio may be one of the starkest examples, but the same situation is playing out around the country. The EIA estimates 27 gigawatts of coal-fired power plants will retire by 2017. Black & Veatch puts the figure at 58 gigawatts by 2020.

There are two EPA rules that are putting pressure on older coal generation: the cross-state air pollution rule, which is currently on stay until further ruling, and the MATS rule, which regulates mercury and other heavy metals and is scheduled to go into effect in April 2015.

Nearly 60 gigawatts could just be the tip of the iceberg if the EPA starts regulating emissions from existing coal-fired power plants as part of President Obama’s climate plan.

PJM has plans for more than $2 billion in transmission upgrades to cope with the nearly 14,000 megawatts scheduled to retire between May 2012 and 2015. Some of the upgrades will build new substations, while others will reinforce or replace transmission lines. More than half of the 130 projects are in Ohio.

In the Midwest Independent System Operator’s (MISO) territory, transmission constraints are also being addressed. In June, a court upheld MISO’s plans to charge its 130 members for a $5.2 billion wind transmission project.

Both MISO and PJM are increasingly turning to energy efficiency and demand response to meet capacity needs. “Demand resources can defer the need for new generation and transmission resources,” PJM wrote in its Regional Transmission Energy Plan. “PJM actively encourages the development of such programs and integration into the capacity market.”

The approach of making better use of available assets, and encouraging energy efficiency, could become a national strategy. Ron Binz, the nominee to head the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), phased out nearly 900 megawatts of Colorado’s fossil-fuel-fired power generation during his tenure at the state’s Public Utilities Commission. The retirements were less about environmental regulations than about risk management.

If energy efficiency and targeted transmission upgrades are going to replace some of the coal going offline, Binz knows regulators need to make it worthwhile, “for example, by adding performance-based financial incentives for efficiency and by eliminating the financial reward for selling more electricity,” he said in 2012.

Regulation tweaks and a smarter grid are already happening at the state and regional levels. “Even with the retirement of older coal-fired generators, we will have enough existing and new resources in the region to keep the lights on,” Terry Boston, president and CEO of PJM, said when the transmission upgrades were announced. “Strengthening the grid through PJM’s proven transmission planning process allows all resources to be used effectively, including renewables, demand response and storage.”