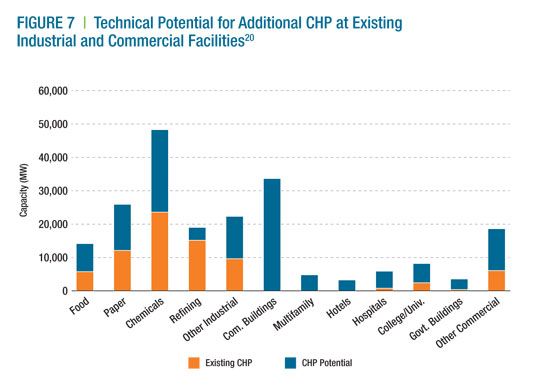

Months before Sandy wreaked havoc on the East Coast, President Obama called for an additional 40 gigawatts of combined heat and power (CHP) in the U.S. by 2020.

The executive order will leverage existing federal policies and technical assistance to encourage CHP, often referred to as "cogeneration," but it could be storms like Sandy that will really push the advantages of CHP systems into the mainstream.

Combined heat and power captures waste heat to use as energy. New York University, which installed a cogeneration system a few years ago, became one of the lifelines for displaced neighbors during Superstorm Sandy as the rest of downtown New York was plunged into darkness. (New York University’s midtown medical facility had a far different fate.)

But the threat of superstorms still might not be enough. At a recent clean energy conference in New York City, industry insiders were supportive, yet skeptical, of the goal of adding 40 gigawatts of CHP to the 80 gigawatts already operating in the U.S.

The call for more CHP is ambitious, but here are five reasons why CHP could be gaining ground:

Superstorms. Large institutions like hospitals and universities are all rethinking their infrastructure with the increasing frequency of serious weather events. In the state of New York, a resiliency retrofit fund will provide credit enhancements to fund upgrades in Sandy-affected areas for projects such as CHP.

Coal retirement. The Midwest and Southeast historically have had low rates of CHP, but with old coal plants retiring, states are looking at other ways to provide energy, according to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. Cogeneration can both run on clean(er) natural gas and also play a role in demand response.

Community energy. Some states and cities are already looking at multi-building and multi-stakeholder CHP opportunities. To get to an additional 40 gigawatts in less than a decade, community energy might be not just nice but necessary, Thomas Bourgeois, deputy director of the Pace Energy and Climate Center, said at the Advanced Energy conference in New York.

Infrastructure "green” banks. Whether you prefer the word "green," "resiliency" or "infrastructure," states are setting up public-private funds that will leverage private capital for energy efficiency and clean energy projects, such as cogeneration retrofits.

The inevitability of distributed generation. Utilities are increasingly seeing the writing on the wall, whether it’s the demand for greater levels of demand management/energy efficiency or the need to rethink how they charge for their services. The result is that some states are rethinking how utilities charge for power while still maintaining the grid. Taking a fresh look at rate structures could potentially benefit CHP, which can also provide other grid services such as demand response.

For every positive trend that could bolster increases in CHP, however, there is a litany of regulatory and regional barriers that will also have to be dealt with, as Adam James, executive director of the Clean Energy Leadership Institute detailed in a recent column.