Real Goods Solar ended its corporate life on the industry's periphery last month, penniless and trading for pennies.

But this isn't just any bankruptcy. A decade earlier, Real Goods Solar grew organically and through acquisition and pulled in tens of millions of dollars in revenue. Four decades ago, the company helped kick off the residential solar phenomenon by supplying panels to off-grid dwellers in the remote forests of Mendocino County, California. It is one of the few companies that has followed the solar industry from its humblest beginnings to its propulsive current state.

That journey stopped on January 31, according to a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The board of Real Goods Solar fired CEO Dennis Lacey and "determined to cease all business activities, to terminate all of the company’s employees, and to commence a plan of action" to file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in Colorado, where the company was headquartered.

The company's share price had been in the tank for years. It even gave up on conventional solar installation on account of losing too much money in that business. The leadership instead pivoted to selling the Powerhouse solar roof technology that Dow Chemical had tried and then discarded in 2016.

Solar roofs failed to save RGS. But a piece of it lives on with founder John Schaeffer, who left the company in 2013 and bought back control of the Solar Living Center, a lush compound in Mendocino dedicated to teaching sustainable lifestyles, including solar power, permaculture and natural construction techniques. He also took back the Real Goods brand from the national installation company, and Real Goods continues to sell off-grid energy equipment under the ownership of the Alternative Energy Store.*

"I wasn’t cut out to be CEO of a giant company," Schaeffer said in an interview. "I was getting tired of it all and longing for the old days."

That old way of life persists, as the solar market claims one more once-bustling enterprise.

No grid, no problem

Schaeffer moved up to Mendocino in the late 1970s, and soon opened the Real Goods store to supply his community with the tools to carve a life out of the remote hills and forests of Northern California.

"All these people were moving up to the country," he recalled. "I discovered that they all needed the same thing: They were tired of kerosene lamps, reading bedtime stories to their kids by candlelight."

One day, someone drove up in a silver Porsche with a handful of photovoltaic panels. Schaeffer said he laid them out in the parking lot and verified that they could charge batteries. Then he added them to the roster of off-grid supplies.

At the time, the technology was a hand-me-down from the space program and had not reached anywhere near the manufacturing scale to make it an affordable household product. Still, Schaeffer sold 10, then 100, then 1,000. Local, off-grid cannabis growers provided crucial early demand.

"They were the only ones who had enough money to afford the solar panels, which were selling for $100 a watt back then," Schaeffer said. He's now working on a museum dedicated to the symbiotic histories of solar and cannabis.

Real Goods survived the '80s and '90s as a mail-order catalog and later merged with eco-lifestyle brand Gaiam. In the first decade of the new millennium, Gaiam's leadership decided it was time to make a push into the nascent rooftop solar industry.

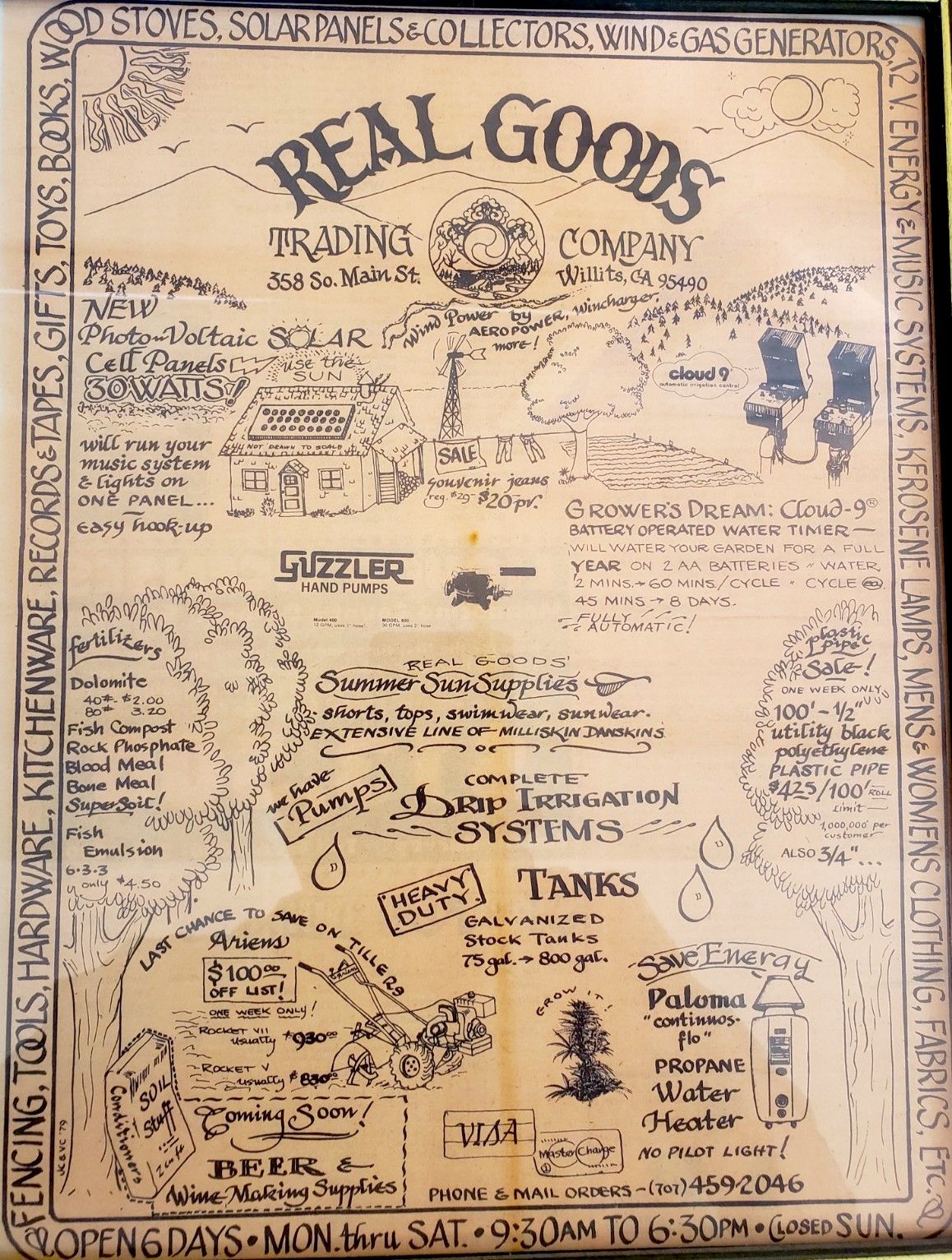

A vintage Real Goods ad displays all the implements needed to grow a homestead off the grid. (Photo courtesy of John Schaeffer)

Growth before a fall

Real Goods Solar went public in 2008, raising more than $50 million from investors. That's a notable feat, coming years before the biggest names in the industry: SolarCity's IPO raised $92 million in 2012; Vivint raised $330 million in 2014; Sunrun raised $251 million in 2015.

Blessed with a pile of cash at a time when few solar installers had it, RGS went on a buying spree. It acquired regional installers including California outfits Marin Solar, Carlson Solar, Independent Energy Systems and Regrid Power, and it later absorbed New England's Alteris Renewables. Pretty soon, Schaeffer said, RGS had become a very large solar company pulling in tens of millions of dollars in sales — all cash deals, as solar financing had yet to take off.

"By 2010, it was boomtown out there," he said of the rooftop solar industry. "Of course, nobody was making any money. It was a revenue game."

Real Goods Solar had a string of profitable quarters around that time, Schaeffer said. But the company grew with each acquisition, and balancing a local team's culture and knowledge with a centralized, national business model became a challenge. The push for scale put pressure on how much time employees could spend taking care of customers and nurturing new sales around the kitchen table.

Schaeffer stepped down from the CEO role in 2010. An enterprise that emerged from "hippies in the woods" built out a professional management team to handle operational scale and financial reporting, rather than sweating it out on a rooftop in the summer. Eventually, they pushed to rebrand as RGS Energy, all but erasing the name that customers knew from decades before.

"That’s when I knew I had to get out," Schaeffer said. After leaving the company, he bought back the Solar Living Center in 2014 and focused his efforts on leading the board of the nonprofit Solar Living Institute that runs it.

RGS Energy hung on as many of the bigger national installers ran out of cash or exited the market: Sungevity, Verengo, NRG Home Solar. SolarCity's meteoric rise ended in a sale to Tesla and a quiet abdication of market share. Sunrun and Vivint have proven to be the rare durable solar installers at a national level.

"It’s just hard to maintain profitability when you’re operating in a lot of different areas," said Barry Cinnamon, whose installation company Akeena Solar also came up in the 2000s, went public and faced similar challenges with the multistate business model.

Financial maneuvers helped prolong RGS Energy's life. Through 2016 and 2017, it repeatedly raised multimillion-dollar sums through common stock offerings. But by that time, the stock price had entered terminal decline. In a truly novel last-ditch effort, the company attempted to revive itself by licensing the solar roof technology that Dow Chemical had abandoned years earlier.

The solar roof market historically has made conventional rooftop solar look easy. Despite the $127 million in "written reservations" the company claimed to have received, it ceased operations a year after installations of its updated solar roof began. That intellectual property could be up for grabs again. The cycle of birth and death continues, just as it does in the fields of John Schaeffer's biodynamic farm.

*Updated to clarify the separation of off-grid supplier Real Goods from national rooftop solar installer Real Goods Solar.