A landmark clean energy law enacted this year in Virginia will only equate to a 26 percent reduction in economywide emissions by 2050, according to a new analysis, leaving the state far from the cuts required to stave off the worst effects of climate change.

Gov. Ralph Northam signed Virginia’s Clean Economy Act in April, establishing 100 percent clean energy requirements for the state’s largest utilities just as the U.S. was beginning to recognize the severity of the COVID-19 crisis. At the time, Delegate Richard C. Sullivan, Jr., leader of the House Democratic Caucus, called it a “historic step forward” for the Southern state.

But even the Clean Economy Act’s requirements for 3.1 gigawatts of energy storage, 5.2 gigawatts of offshore wind and 16.1 gigawatts of solar and onshore wind fall short of the action required to wring emissions from the electricity sector, according to an analysis released Wednesday by Rocky Mountain Institute and research firm Energy Innovation.

As more and more states establish 100 percent clean electricity targets, lingering policy gaps are being revealed, according to the analysis. The coronavirus pandemic, which has shrunk state budgets, has heightened some of those existing hurdles.

The Virginia analysis is the first that RMI and Energy Innovation have completed in a planned series of assessments of energy policies in 20 U.S. states.

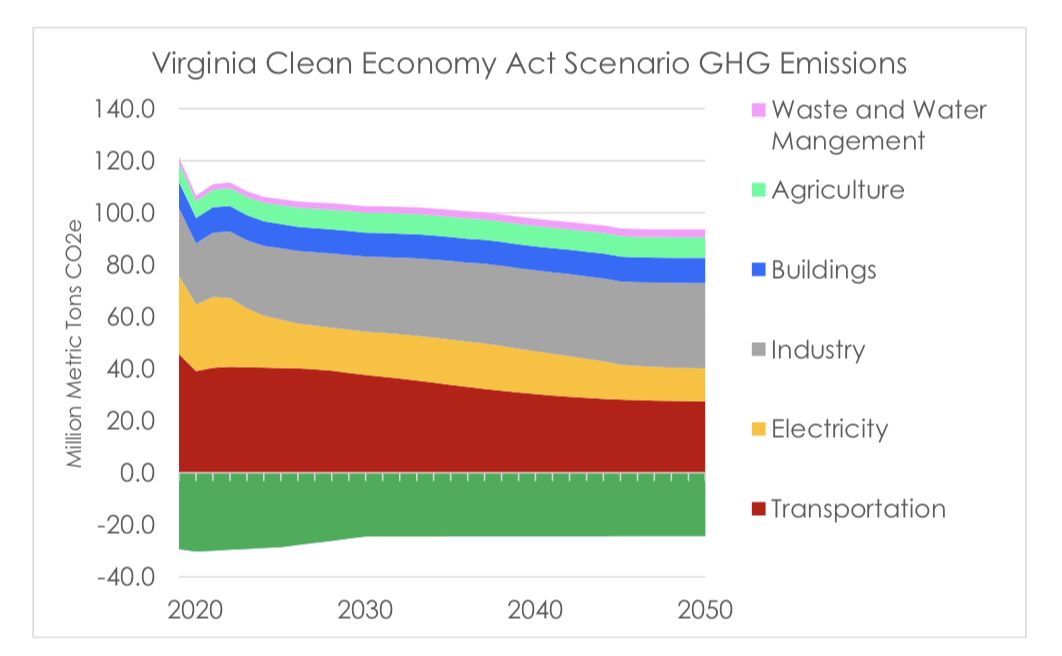

Using publicly available data and their peer-reviewed energy policy simulator, RMI and Energy Innovation cataloged Virginia’s current greenhouse gas emissions — over half of which come from transportation — and analyzed policies in line with the limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming that has been established by scientists. The model achieves net-zero emissions before 2050 and reductions at 63 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

Credit: Energy Innovation and RMI

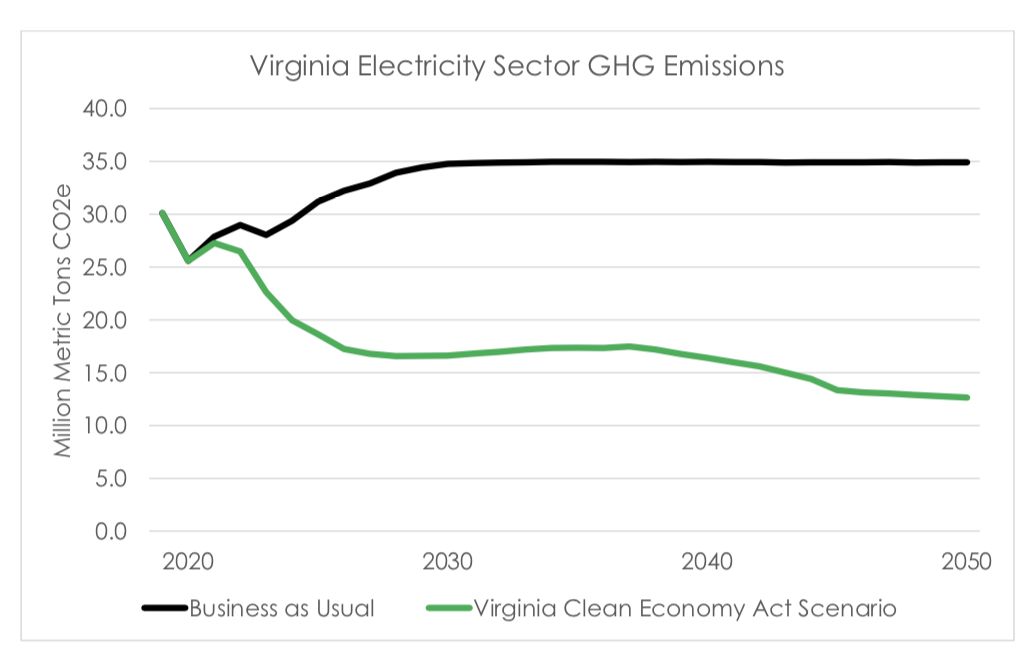

The Clean Economy Act zeroes out electricity emissions only for the state’s large utilities, Dominion Energy and Appalachian Power. That reduces power-sector emissions by only 64 percent by 2050. The analysis recommends extending requirements to municipal and cooperative utilities and shortening the decarbonization timeline to 2035. Achieving fully clean electricity will require even more work: The analysis does not account for emissions related to imported electricity, which Energy Innovation modeled as about 19 million metric tons per year.

Credit: Energy Innovation and RMI

To draw down transportation emissions, RMI and Energy Innovation modeled an EV mandate requiring all-electric car sales by 2035 and all-electric trucks a decade after that. Virginians would also be required to reduce passenger car trips by 20 percent by midcentury. The model’s analysis of the transportation sector does not consider the potential for resale of used internal-combustion vehicles, however, which is allowed even under a recent California order that bans gas-powered cars after 2035.

Industrial users would electrify or switch to fuels such as green hydrogen by 2050. All building equipment would be electrified by 2030. Carbon capture and storage would help with some remaining emissions from the industrial sector. Land use in the heavily forested state would also contribute to carbon sequestration.

Clean energy vs. COVID-19?

After Virginia, the two firms will take on an analysis of potential policies in more than a dozen other states including Minnesota, Nevada and Colorado. Nevada has passed 100 percent clean energy legislation, while Colorado has a mandate to draw down emissions 90 percent below 2005 levels by midcentury.

“We envision a mix of states that have [recently enacted] and strong policy, states that are considering it, and states where the case is yet to be made,” said Amar Shah, manager of building electrification at RMI.

While coping with a deluge of new coronavirus infections, states are in the midst of decisions about whether clean energy and climate policies will need to be cut back as part of pandemic-related austerity or become targets of stimulus designed to coax the economy back toward health.

The data from RMI and Energy Innovation’s analysis backs arguments for the latter vision. That ideology has also gained an ally in the White House. President-elect Joe Biden, who helped implement the clean energy provisions of the 2009 stimulus package, has linked a transition to clean energy with the need to boost the economy.

“One of the real values of the tool is in looking at the jobs and economic growth potential of different policy options and packages of policy coming out of COVID[-19],” said Robbie Orvis, director of energy policy design at Energy Innovation and an author of the report. “Transitioning to a low-carbon economy requires building a lot of stuff, and a lot of that is directly translated into jobs.”

The economy has lost more than 450,000 jobs in clean energy and energy efficiency since the pandemic began, even after employment increases in recent months, according to data released Wednesday by E2, E4TheFuture, the American Council on Renewable Energy, and BW Research Partnership.

In Virginia, the RMI and Energy Innovation scenario forecasts the addition of 12,000 job-years, a measure equating to one job for one year, and annual additions of $3.5 billion to the state’s gross domestic product by 2050. The model also highlights health impacts, with lower pollution levels leading to the avoidance of 900 asthma attacks per year by midcentury.