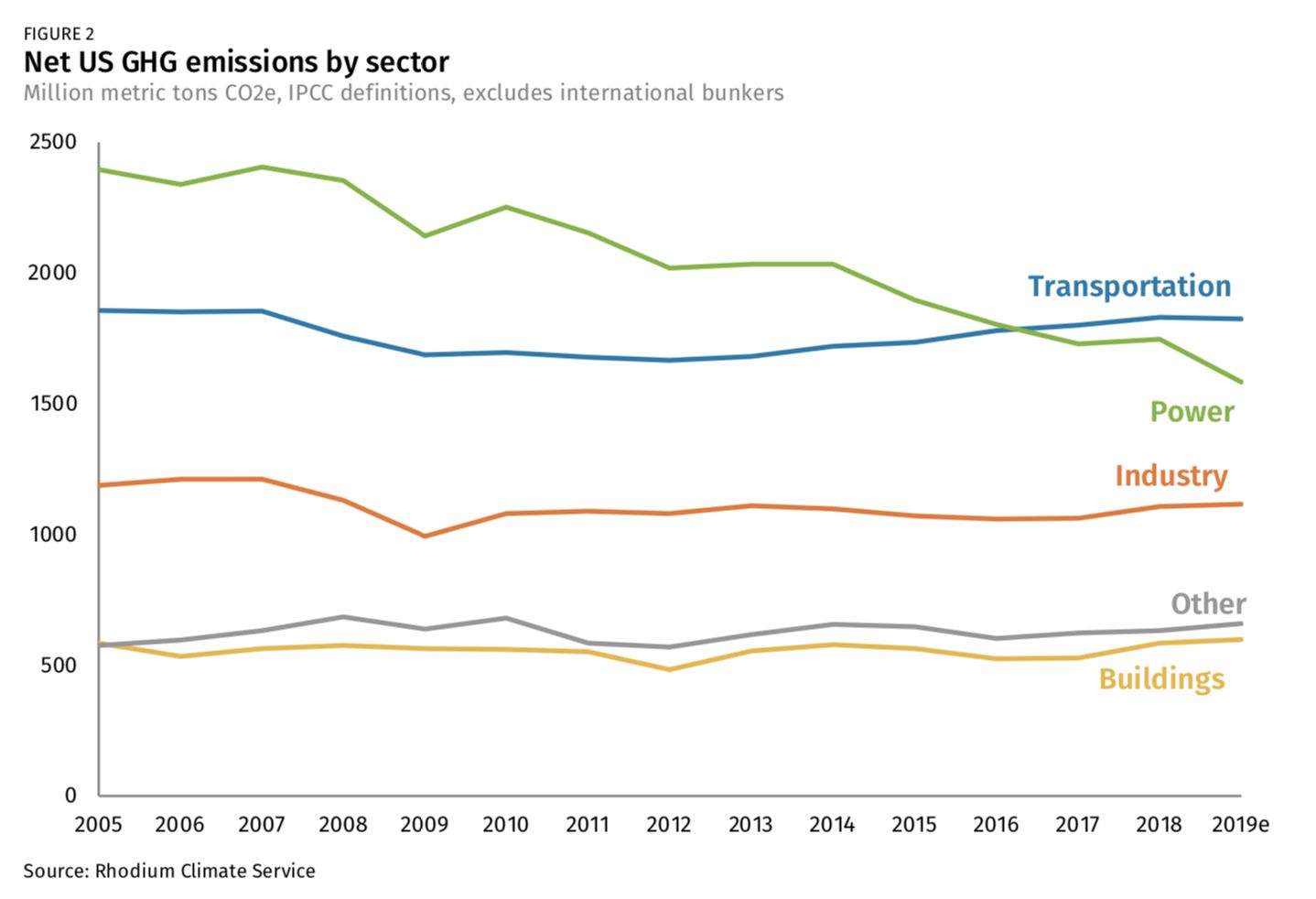

U.S. emissions likely fell in 2019, putting the country back on a downward emissions trend, according to newly released analysis from research firm Rhodium Group.

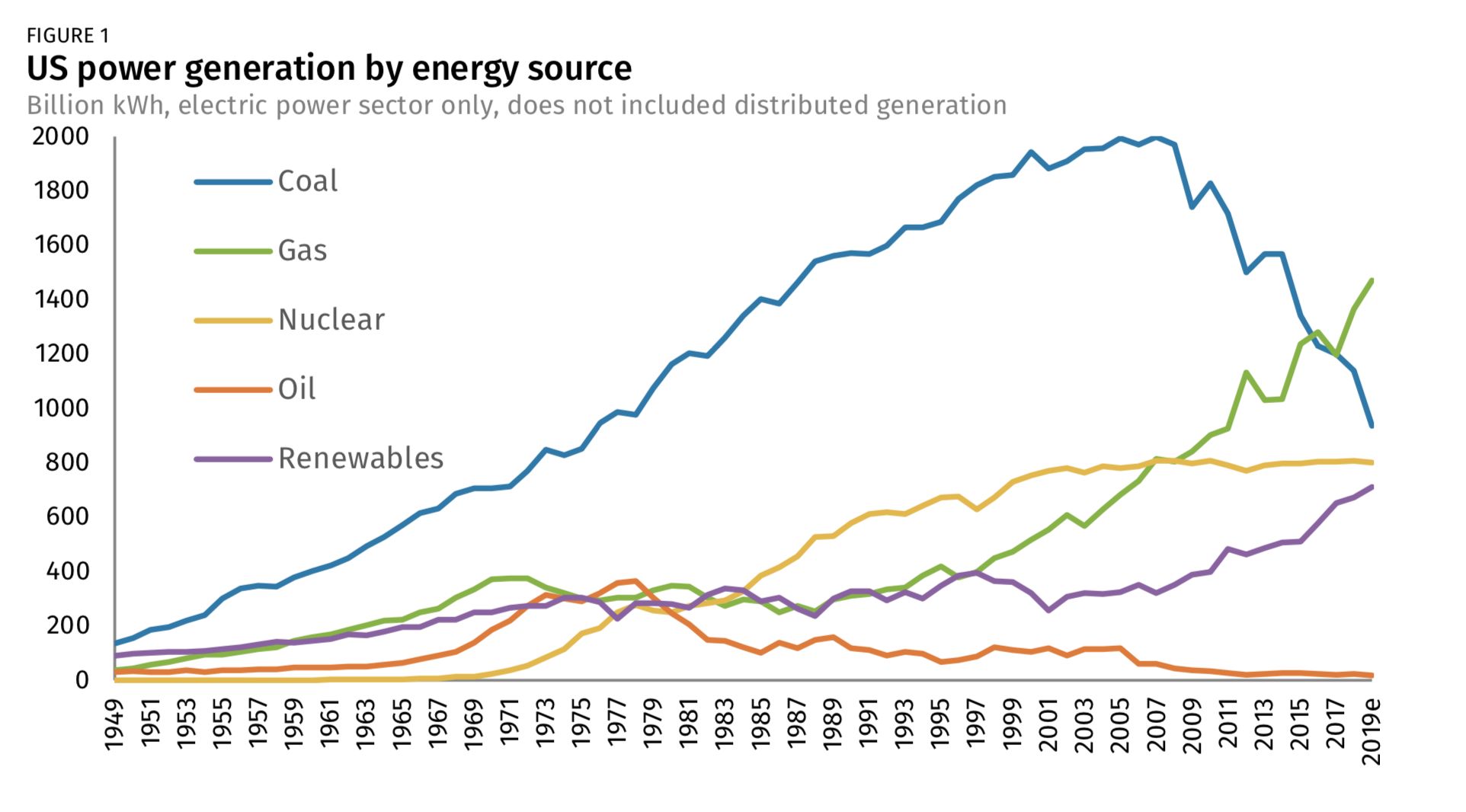

The results, which estimate a decline in greenhouse gas emissions of around 2 percent in 2019, contrast with 2018, when emissions rose for the first time in three years. Rhodium attributes much of the 2019 turnaround to the electricity sector, where technologies such as wind and solar, in addition to super-cheap gas prices, continued to erode the dominance of coal-fired power.

But emissions increases in other sectors tempered the 10 percent reductions in the power sector.

“[It] shows how much coal matters, because in reducing generation from coal we get pretty sizable reductions in the power sector. But at the same time, it shows the limit of coal-led reductions in power, and of the power sector overall, in bringing down economywide emissions,” said Hannah Pitt, a senior research analyst with Rhodium's climate and energy group. “There is only so much you can squeeze out of the power sector before you really need to start seeing reductions in other sectors.”

While electricity emissions declined and transportation emissions remained fairly flat in 2019, Rhodium estimates that emissions from buildings, industry and other sectors increased.

Taken together, the U.S. is still dangerously far from the targets set out in the Paris Agreement, whether or not President Trump is successful in his bid to withdraw the U.S. from the agreement.

As part of the landmark pact negotiated in 2015, the U.S. pledged to reduce emissions 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. But average national reductions since 2005 haven’t exceeded 1 percent, according to researchers. To meet the Paris goals, Rhodium says, the U.S. would have to bump that percentage to between 2.8 and 3.2 percent. And countries are already supposed to be strengthening their national targets, which has the potential to move the finish line when many countries are hardly through their first lap.

The results from Rhodium once again underscore the difficulty of drawing down emissions in sectors devoid of the “low-cost technology alternatives” that Pitt says exist in the power sector. “The industrial, agriculture and waste sectors remain largely untouched, either by policy or technology innovation,” according to Rhodium.

In the power sector, the news is comparatively brighter. According to Rhodium's estimates, U.S. coal generation experienced a historic year-on-year decline, falling 18 percent last year. Over the whole decade, the U.S. halved its coal generation.

Source: Rhodium Group

Renewables supplemented a chunk of that decline, with large-scale renewables (including hydro) increasing 6 percent in 2019. But a sharp decline in gas prices, which were down 20 percent last year, took a bite out of the emissions reductions tied to coal retirements. Pitt said competition between solar and wind versus natural gas will be a trend to watch going forward (Wood Mackenzie data indicates solar will edge out gas in many circumstances).

“As coal retires, there’s an opportunity for those technologies to stand behind it. One of the forces that threaten that is just how cheap natural gas is,” said Pitt. “Once we have retired the coal plants we can retire in the U.S., then cheap natural gas could be crowding out cleaner sources in the future.”

That’s where policy can play a role. Although the Trump administration, according to tracking from The New York Times, has worked to roll back or change more than 90 environmental rules and regulations — such as automobile efficiency standards, restrictions on methane emissions and the Obama-era Clean Power Plan — Pitt says state-level action is helping to curb the impact, if only slightly.

But if the U.S. is to make the serious changes called for by scientists, who have warned of dire circumstances if climate action doesn’t happen soon, federal policy will have to play a bigger role. Though market forces also contribute, federal policy is “the most effective way” to push emissions down to Paris-acceptable levels, according to Pitt.