The Bonneville Power Administration is taking its first step into “non-wires alternatives” for power grid investments -- not necessarily by choice, but certainly with a lot of preparation in advance.

Last week, the federal agency that manages the Columbia River hydropower complex and power grid across the Pacific Northwest announced it has given up its nearly decade-long effort to build a new transmission line along the I-5 corridor. The project, which faced public opposition from the start, has also ballooned in cost from an initial estimate of $346 million to more than $1 billion.

Instead, BPA will turn to non-wires alternatives -- demand-side resources like efficiency and demand response, as well as distributed energy such as rooftop solar -- as one of several parts of its replacement plan.

Non-wires alternatives are starting to take a role in distribution grid investment planning in states like California, New York and Hawaii. But Bonneville’s pilot project is taking the concept to the transmission system, or more specifically, a portion of stressed-out line between the cities of Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, Washington, the most heavily populated part of the Columbia River basin.

While BPA isn’t looking to these resources to make up for all of the reliability and capacity it will lose by ditching the I-5 transmission project, it is eyeing them to serve an increasingly important role in its plan for “more scalable and flexible investments in the federal transmission system,” CEO Elliot Mainzer wrote in a letter last week.

The first test will come this summer, when BPA launches its first non-wires measures effort, he wrote. This two-year pilot project got started in February 2015, when BPA executed a two-year contract with a demand response aggregator for the project. In April 2016, it launched its first RFO, seeking third-party capacity in the form of incremental energy, decremental energy, and demand-side load reduction, available for up to four hours during times of summer peak congestion.

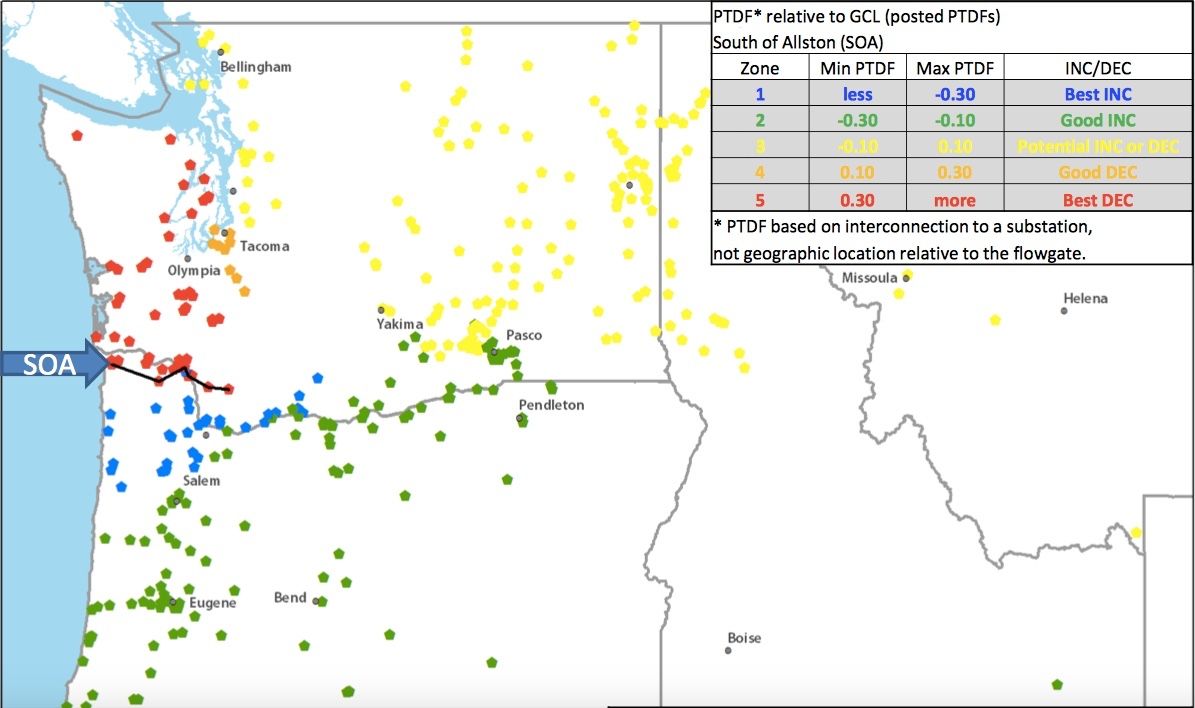

Incremental and decremental energy -- ramping generators up or down in response to grid operator commands -- can be supplied by anything that can push electrons onto the grid. Demand-side management can be supplied by anything that can reduce or curtail its use of grid power, from heavy machinery to household air conditioners. This map below from BPA shows where it’s looking for both kinds of energy, while demand-side resources could be expected to be most valuable near the biggest loads, such as the Portland-Vancouver region.

Bonneville didn’t put much value on non-wires alternatives in its initial analysis of their capability to replace power lines. In 2011, it commissioned a study that found they could delay the upgrade until 2022 -- but mostly by relying on “redispatching certain generators at peak times to reduce transmission flows along the I‐5 corridor below the path ratings." In other words, getting big generators to behave differently.

While it also studied energy efficiency, distributed generation, and demand response measures, it found that they “appear unlikely to enable sufficient transmission flow reduction to defer the I‐5 project need by more than a year.”

Of course, things have changed a lot since 2011. The cost of rooftop solar has plummeted, making it potentially competitive even in a region with some of the country’s cheapest electricity. Demand response is becoming more sophisticated and widespread.

And energy storage, which wasn’t analyzed in the first report, is now a viable alternative as well. Lithium-ion batteries that would have been science experiments at the start of the decade are now being installed at homes and businesses across the country, albeit in small numbers and mostly limited to states with incentives to boost the business.

Mainzer noted that BPA is looking to batteries as part of its solution: “We also will look to use cutting-edge grid technologies such as battery storage and flow control devices to proactively manage congestion and further extend operational capacity of the existing system.”

Transmission system operators are under a lot of pressure to ensure that anything that replaces a power line upgrade has to be as reliable as the alternative -- or at least, reliable within certain margins of error.

Mainzer noted that the decision to abandon the I-5 project “reflects a shift for BPA -- from the traditional approach of primarily relying on new construction to meet changing transmission needs, to embracing a more flexible, scalable, and economically and operationally efficient approach to managing our transmission system.”

As part of that push, Bonneville has also been beefing up its demand response capabilities. The agency has traditionally relied on old-fashioned direct communications between grid operators and big industrial loads like aluminum smelters or lumber mills. But in 2014, it launched a project to tap aggregations of smaller loads, and adjust them up or down in 10-minute increments -- a speed and flexibility it’s also calling for from its non-wires alternatives pilot participants.

This 2016 presentation from Bonneville explains the link between this demand response work and its non-wires alternatives work. It also lays out future steps, such as establishing a budget for non-wires development and demonstration in its 2018-2019 rate case, and benchmarking other demand response programs across the country to “save costs and keep rates as low as possible.”