For more than a decade, Oerlikon, a Swiss conglomerate owned by a Russian oligarch, ran a modestly unsuccessful amorphous silicon (a-Si) solar manufacturing equipment business.

In March 2012, the a-Si equipment division of Oerlikon was divested to Tokyo Electron (TEL) in a $275 million deal.

Late last year, Applied Materials, the chip-making equipment giant, agreed to buy Tokyo Electron in an all-stock deal valued at more than $9 billion. Applied is the top builder of semiconductor manufacturing equipment; Tokyo Electron was number three.

Today's news is that Tokyo Electron has withdrawn from the photovoltaic panel production equipment business.

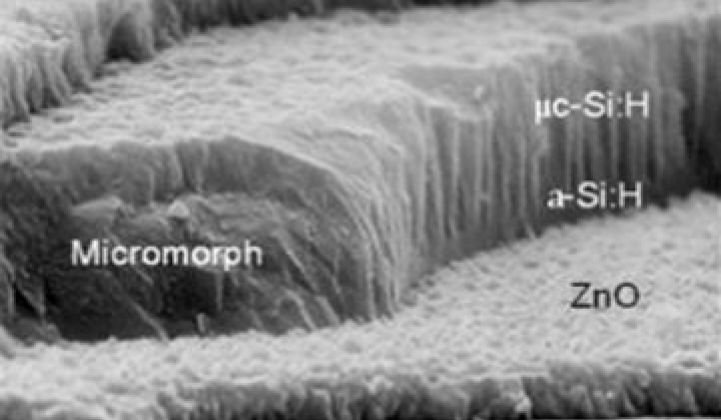

That means that Oerlikon's a-Si business has finally been laid to rest, with the closure blamed on a weak market and an oversupply of production equipment. The real blame, however, lies with the fundamental disadvantage of a-Si PV panels in efficiency and cost.

Way back in July 2010, in a bit of drama, Applied Materials discontinued its SunFab line of a-Si thin-film solar panels and cut about 500 workers. As we've reported, Applied entered the amorphous silicon solar business in 2006 through acquisitions and envisioned factories that would produce gigawatts' worth of large-scale solar panels each year. The center of the strategy was SunFab, a factory-in-a-box product. The company landed early clients like Signet Solar, Suntech and Masdar PV.

But low efficiencies (below 11 percent), high costs, and cheap Chinese crystalline silicon doomed a-Si and Oerlikon's effort. In 2010, Applied cut its losses and killed its business. And now it has essentially done that once again by terminating Oerlikon's a-Si business, as per TEL's statement today.

Amorphous silicon solar technology has a troubled commercial track record. In addition to Applied, other defunct a-Si producers include OptiSolar, Sencera, and ECD. Sharp entered the 3Sun JV with Enel and ST Microelectronics in a-Si a few years ago and still has the vestiges of its a-Si business. Also struggling to remain competitive in amorphous silicon and its variations are Xunlight, HelioSphera, and NanoPV.

Shyam Mehta, GTM Research's Lead Upstream Analyst for Solar, lays it down:

"TEL's exit from the thin-film PV equipment space was a long time coming. Due to rampant overcapacity, the market for PV capital equipment has been practically nonexistent since 2012, all the more so for thin-film PV. China's recent ban on 'pure' capacity expansions was likely a body blow to whatever remaining aspirations TEL had, and it has lost out to competitors such as Schmid in penetrating emerging local demand-driven markets such as the Middle East and South America in 2013. With crystalline silicon costs benefiting from the overcapacity-driven collapse in polysilicon prices and module efficiencies of 15 percent and higher fast becoming the norm, the value proposition of low-efficiency thin film has been rapidly eroding over the past few years. Finally, after experiencing the commercial failure of its amorphous silicon SunFab technology in 2008-2010, Applied Materials, which now owns TEL, wasn't going to make the same mistake twice."

Mehta notes that there is still hundreds of megawatts of a-Si production equipment capacity, currently dormant, in the global market.