When Simon Property Group chose Sensity Systems to supply LEDs for some of its parking lots, it was buying solid-state lighting primarily for the energy savings. But the mall company was also interested in the possibility of leveraging sensor nodes on the lights for things like measuring snowfall depth for more efficient plowing and leveraging video to enable smarter parking for its customers.

It's that type of futuristic internet-of-things product that was front and center at Lightfair International in New York City this year.

Networked LEDs are often touted as the critical nodes to smarter built environments, from individual buildings to entire cities. After all, lights are everywhere. From identifying a burgeoning vermin infestation in a warehouse, to helping hospitals more quickly locate crash carts, to first responders being able to visually assess an emergency as they are en route to it, the promise of LEDs was depicted as limitless during pitch sessions at the show.

But the reality is that not every customer is rushing to shell out for systems that they do not need now and are unsure of how to use in the coming years. On the other hand, savvy corporations and municipalities want to invest in the most cost-effective, future-proof systems possible as they switch to LEDs.

“The internet of things is sitting firmly at the peak of inflated expectation,” said Aaron Kless, director of applications engineering at Digital Lumens. “In the industry, it’s often too much about what we can do instead of what we should do.”

The allure of smart cities

The switch to LEDs in cities is driven by energy control and cost savings. But that’s just the no-brainer part of the pitch.

“How many other systems could you eliminate?” Austin Ashe, sales manager with GE, said of cities upgrading to LED streetlights packed with other sensors and video capabilities. “It becomes their own app store.”

GE is testing its LED streetlights with sensors and the company's Predix software in San Diego and Jacksonville, Fla. Both cities have about 50 units. The streetlights can collect information on noise, temperature, wind and air pollution, while also using cameras to analyze traffic and parking flows, as well as to provide greater security. The idea is that the information could be used by everyone from first responders to citizens to developers.

The appeal is that the hardware can be paid back through the energy savings, and everything else could be covered under a software-as-a-service platform. Streetlights cost the U.S. $6 billion to $8 billion annually for energy and maintenance. That has made a lot of city planners take a look at LEDs.

The market for LED streetlights as the entry point for the smart city has attracted major lighting vendors, such as GE, Philips and Cree, as well as networking giants like Cisco (which works with Sensity), smart energy network companies such as Silver Spring Networks and Itron, and startups like Petra Systems.

Part of the problem is that the sales pitch goes beyond just the transportation department, cutting across the various silos of city services. Just as with many electric smart grid projects that were billed as transformational, the true change can only come if every department is invited to the table to leverage the investment and siloed budgets are shared.

In Los Angeles, which has the largest LED streetlight project to date, the lights were initially installed with a network from Philips being layered on later. Few cities today are thinking holistically about developing the apps that sensored streetlights might offer when they make the investment based on energy savings.

Ideally, any applications would benefit the city’s populations as well. GE’s Predix platform has an API that can be offered up for developers to use the data coming off the sensors embedded in the LED. The question, however, is what various city departments may deem to be a security risk to share and how much pull there will be from citizens for greater transparency.

Retail hype

The payback for streetlights and other outdoor lighting networks makes the switch to LEDs an increasingly obvious choice, especially with the proliferation of financing options that keep the spend away from capital budgets.

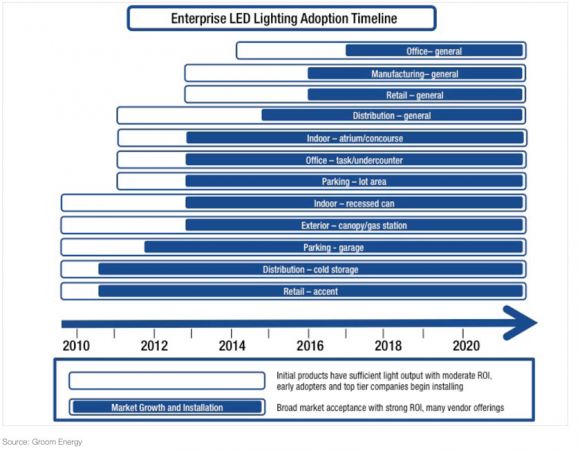

Often the thought process is, “Well, if it’s the last time I’m going to get a bucket truck to go up this pole, I guess I’ll put in video and some sensors,” said Jon Guerster, CEO of Groom Energy, an energy efficiency and sustainability consulting firm. If the financing terms are right for the extra bells and whistles, cities will adopt them, even if they don’t use them right away. When it comes to general retail, however, “I don’t buy it,” he said.

He’s not alone. “It’s a lot of baloney,” Zach Gentry, VP of marketing at Enlighted, a lighting network company, said of many of the applications -- especially for retail -- that were being touted at Lightfair.

That’s not to say Enlighted didn’t have its own pitch for its customer base. Gentry noted that there are applications, such as helping hospitals find their crash carts faster, which they can do cheaper and more accurately with sensors during a lighting upgrade than the hospital could do previously with RFID technology.

Gentry noted that applications around safety and security were plausible selling points. Environmental sensors for specialized environments, such as biotech and food processing, are also attractive for embedded sensors in LEDS, according to Guerster.

Beyond specialized environments, however, there is a question as to whether the end goal can be met through another network. GE just announced a partnership with Qualcomm to allow retailers to pinpoint a shopper’s location when they’re within the store. Using LED networks, they can push messages to shoppers as they move through a store.

Although many of us accept Amazon browsing tracking us around the internet, the idea of a store pushing you messages as you roam through their brick-and-mortar location might be too close to Big Brother. With ubiquitous GPS technology, stores can already push notifications across their apps to customers as they enter parking lots or the store’s front door.

Energy savings still drive the LED invasion

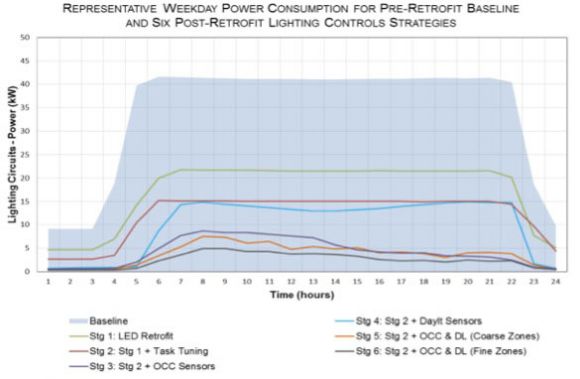

Despite the hype, LEDs are being installed because they save money. Digital Lumens’ Kless said that smart lighting is a Trojan horse, but then went on to cite one example of the increased energy savings that come from leveraging sensors to use LEDs even more efficiently.

Source: Digital Lumens

In a pilot Digital Lumens did with Pacific Gas & Electric, the savings of switching to LEDs were significant, but they were able to cut energy use by 93 percent with more sensoring. For some applications, however, just the savings from basic occupancy sensors may be enough.

For other markets, like grocery stores, the quality of the LEDs is key, so that produce looks fresh and meat doesn’t take on a gray tinge. Guerster said that his customers are looking for broader energy consumption insight from sensors and LED networks, and not necessarily leveraging those sensors for entirely novel applications.

Although the bright, steady light of LEDs has largely been praised for increasing safety in cities, there has also been some pushback as the cold, white light of LEDs washes into some people’s bedrooms and businesses from streetlights. As more cities upgrade to LEDs, the ability to adjust the lights not only due to environmental conditions, but also in response to angry citizens, could become increasingly important.

Enlighted's customers, which include technology and financial firms, are looking for more granular sensor data to drive more efficiency from the lights. Even for mall companies that have dreams of apps that are all enabled by LED networks, “it’s still about power savings,” said David Lancaster, field services manager for Sensity. “There’s just a toe dipping into video nodes. Not a foot, just a toe.”