California’s 2020 goal of generating a third of its power from renewables will be more complicated than just building enough solar power plants, utility-scale wind projects, and geothermal facilities.

Renewable energy, much of it variable, must be delivered to and integrated in the state’s transmission system. Responsibility for 80 percent of the state’s power falls to the California Independent System Operator Corporation (the ISO). The ISO has to meet the goals set by the state’s political leaders, its energy commission, and the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) while adhering to regulation by federal and regional authorities that focus on grid reliability.

Decision-makers at the ISO are preparing for the big changes necessary to achieve the 33 percent renewables goal without forgetting their experience in the 2000 and 2001 energy crisis, when multiple outages cost the state $40 billion to $45 billion and the sitting governor was recalled.

“I was Director of Grid Operations, so I was in the control room pretty much for the duration,” said ISO Executive Advisor for Operations James McIntosh. “Renewable energy had nothing to do with that.”

But there are parallels between those events and what could be coming.

"The challenges that we had were many,” McIntosh explained. “Demand was outpacing supply, dry winters caused low hydro conditions, natural gas prices were skyrocketing and market abuse mitigation was not at the level it is today.” But what could be in store for California, reminiscent of that time, he added, was the fact that “there was a capacity shortage as the result of 33 plants going off-line for emissions standards upgrades required by California’s air quality authorities.”

McIntosh said he has no doubt that “we have the technology and the means to make the policy goals happen, and the ISO is working hard to prepare for successful achievement of important environmental goals. But there are going to be challenges as we get to increased penetration levels of wind and solar.”

“At all levels of the ISO,” McIntosh said, there is attention to the state’s readiness to apply the newest grid dynamics to cope with wind and solar variability and the fact that, without energy storage, there is no way to use their off-peak capacity to meet peak demand.”

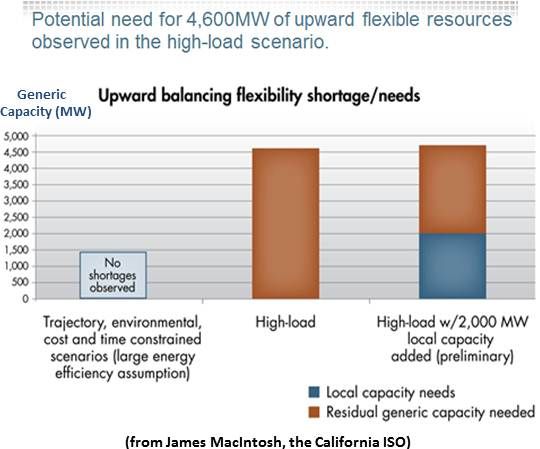

But, once again, imposed mandates could induce a capacity shortage. “Probably the biggest challenge is maintaining the ramping capability and ancillary services capability,” McIntosh said, because the state has mandated that, as of 2017, power plants using coastal and estuary waters for cooling be retrofitted, repowered or retired. This “once-through cooling mandate” affects 11 natural gas plants accounting for up to 12,000 megawatts of capacity on the ISO grid by 2020.

Determined not to let history repeat itself, the ISO has asked the Federal Energy Commission (FERC) for a waiver on the retirement of Calpine’s eleven-year-old gas-fired Sutter Energy Center. “We’re trying to keep the grid reliable by keeping this supply source available to us,” McIntosh explained. “We’re kind of putting a stake in the ground and saying we need this plant to be there to handle the risk of the once-through cooling plants going away.”

Federal (FERC) and state (CPUC) regulators are tussling over the Sutter plant waiver, said Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies Executive Director V. John White. “The good news is that the ISO is thinking about more than natural gas,” he added.

“The problem is the CPUC is looking at resource adequacy as just keeping the lights on,” White explained. But the challenge is very different now. “As variability is introduced on the generation side, we need more gas -- but as capacity. We want to pay for it to be available but not to run.”

McIntosh had a similar take. California’s combined-cycle gas-fired plants, which do not use controversial water sources for cooling, will become progressively more important for grid reliability. As the penetration of variable renewables grows, he said, they will be vital for ramping and other forms of flexibility.

Uncertainty is accentuated, he added, by the unknowns associated with integrating distributed renewables and the coming plug-in vehicle fleet.

“What the ISO is concerned about is time,” White explained. Without resource planning, there may not be adequate replacements for the plants that must be closed by 2017. The CPUC, he added, should design its Resource Adequacy program, which determines what generation the state will need, with a five-year planning perspective instead of its present “one-year snapshot.”

A broader perspective was also McIntosh’s prescription. “It’s not just one thing that has to happen” to achieve the 33 percent renewables target,” he explained. “It’s a number of things. And a lot of players will have important roles in making this happen.”

“We want to keep the grid reliable, address the policy issues, and do it at the least cost. Every time we make a decision, we think about all those things,” McIntosh said. But, he added, “There will be a cost. Nobody said it would be free.” The job of the ISO, he said, “is to make sure we keep that cost as low as we possibly can.”