After premiering its 2.5-megawatt, 120-meter rotor Brilliant wind turbine in February, GE is now announcing the commercial installation of the first three models that will integrate energy storage capability.

GE's (NYSE:GE) engineering advances have long been moving toward two broad objectives: achieving a more rapid and comprehensive automated response by the turbine’s multiple onboard computer systems to the enormous amounts of data the machine’s network of sensors can deliver, and allowing GE’s centralized operations centers to wirelessly control variables that the turbine’s automated response fails to manage. These variables range from a change in wind or local grid conditions to a lightning strike.

Like many of the best turbines, the GE Brilliant machine’s networking infrastructure and wireless communications allow it to interact with input from its own sensor system and the internet. It can assimilate detailed weather forecasts, grid energy supply-demand needs, and transmission system frequencies and voltages to adjust its operations and increase efficiencies in everything from power electronics to blade positioning.

The new height, rotor length and data analytics makes the Brilliant turbine 25 percent more efficient than its previous 2.5-megawatt machine, according to GE.

Similarly, Vestas promised comparable advances with an even bigger (3.3-megawatt) nameplate capacity and an even larger (126-meter) rotor diameter: “At a low wind site based on certain conditions, choosing a V126-3.3megawatt instead of a V112-3.0 megawatt turbine boosts annual energy production by up to 19.5 percent.”

Siemens (NYSE:SI) said its new 2.3-megawatt, 113-meter rotor turbine is “a result of more than 30 years of research and development” and can “harvest more energy out of moderate wind conditions than anyone thought possible.”

Navigant/BTM Consulting put GE’s market share of the 2012 global wind turbine market at 15.5 percent and the share of perennial leader Vestas at 14 percent. MAKE Consulting put Vestas ahead, 14.6 percent to 13.7 percent. In both studies, Siemens was third by a significant margin.

GE has also announced that three Brilliant turbines will be installed by Invenergy at a Texas wind project by the end of 2013. Each will integrate 50 kilowatt-hours of battery storage, allowing the individual turbines to add a set of three possible functions.

The batteries, situated on a nearby ground pad, are integrated by the turbine’s intelligent operating system. They make three uses of storage, which GE calls applications, available to project operators.

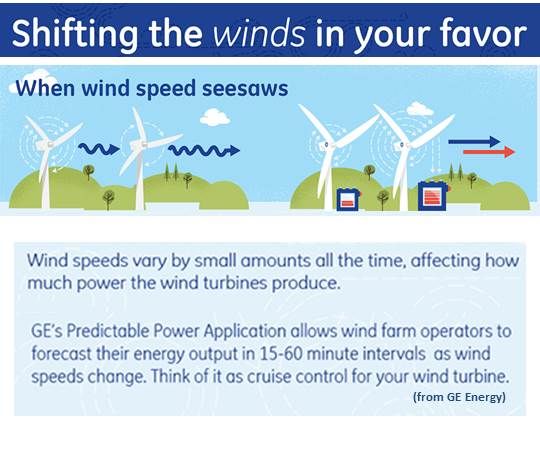

The Invenergy turbines’ storage will be used for the first of the apps, labeled "predictable power" by GE. That is short-term storage to “sure” the delivery of committed output, explained GE Wind Product Line General Manager Keith Longtin. Increased certainty that a wind project will meet contractual obligations makes it more competitive with generation sources that face fewer intermittency challenges.

Stored electricity can also be sold to grid operators like PJM, ERCOT and the California ISO to regulate frequency variations that can disrupt service. Selling into frequency regulation markets adds a revenue stream for a wind developer, Longtin said.

Third, storage allows "ramp control." Electricity generated when the blowing wind allows production but the grid is not buying can be sold when it is needed, Longtin said, increasing developers’ returns on investment.

The Invenergy turbines will use GE Durathon sodium nickel chloride batteries, but the company is “battery-agnostic,” Longtin said. “Each application can require a different amount of storage and/or a different battery chemistry.” Frequency regulation requires a quicker responding power battery. Ramp control is more efficient with an energy battery with more storage capability.

According to Longtin, it is not about the battery, but the ability to assimilate and use data and integrate the storage through the turbine’s existing power electronics to eliminate extraneous costs associated with add-on storage.

“Every application will be a little different, but 25 kilowatt-hours to 50 kilowatt-hours of storage is adequate for any of the three applications,” Longtin said. “The 50 kilowatt-hours will give you predictable power in the range of 30 minutes. If there is a reason for 60 minutes [of storage], it could be doubled.”

The turbine’s converter limits storage to 350 kilowatts which, Longtin said, is difficult to translate into kilowatt-hours because of variables like the amount of energy needed and how fast it is needed. The point is, he said, “we have a customizable solution.”

The Brilliant turbine is a platform to host a suite of applications, Longtin said. Integrating a small amount of battery storage offers applications that allow wind developers better turbine productivity and new revenue streams.

“We are not working on large-scale storage for arbitraging or moving power from night to day,” Longtin said. “Batteries would have to come down to a cost point to us on the order of $200 per kilowatt-hour. It is on the order of $800 per kilowatt-hour to $1,000 per kilowatt-hour today.”