The California Public Utilities Commission has approved the biggest-ever utility investment into EV charging — $738 million for the state’s three big investor-owned utilities to raise from ratepayers and put toward infrastructure and rebates, plus an additional $29.5 million for program evaluation.

The decision, part of the CPUC’s mandate under the state’s broad-reaching clean energy bill, SB 350, is a major step toward aligning the utility sector with meeting the state’s goal of deploying 5 million EVs by 2030, and slashing the transportation sector’s 40 percent share of Golden State greenhouse gas emissions.

But how is it going to work? The decision passed by the CPUC last week (PDF) settles many key policy and funding decisions for good, at least in terms of the first big wave of utility spending for medium- and heavy-duty EVs. But many of its primary policy levers, such as new time-of-use EV charging rates meant to align fleet owners’ incentives with the needs of the state’s power grid, are still to be worked out. Other factors, such as how utilities might someday get to own and rate-base EV chargers, as well as the supporting infrastructure, remain open to a potentially contentious debate in the months ahead.

And of course, whether customers will make the shift to electric buses, trucks, forklifts, and other fleet vehicles en masse, and where they end up being located on the grid, is largely outside of utility control. That leaves much of the execution of the plan open to adjustment in the years ahead.

Here’s our outline of the CPUC’s 165-page document (plus appendices), noting the key changes from utility proposals to final approved programs. This column also highlights important innovations in rate design, like SCE’s waiver of demand charges for the first five years — a big deal for projects that can be crippled by high demand charges — and the interesting opportunity before SDG&E to work with ratepayer advocacy groups to test utility ownership of residential EV chargers under a performance-based model.

From utility proposals to final product, a re-emphasis on the poverty-pollution nexus

The first thing to note in the CPUC’s new decision is that, while it retains parts of the plans originally submitted by Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric, it also makes major changes. The most glaring shift was reducing total spending from the more than $1 billion they collectively initially requested.

The CPUC denied SDG&E’s medium- and heavy-duty vehicle charging proposal, for instance, and dashed its hopes for owning residential EV chargers themselves — at least for now, which we'll cover at the end of the article. To date, utilities have been allowed to own everything except the charging infrastructure.

Regulators also reduced rebate rates for SCE and PG&E, and corrected a $100 million overcharge in SCE’s proposal — a whopping accounting mistake caused by a miscalculation of cabling costs, no longer reflected in SCE’s $356 million total figure.

But the biggest change was shifting the bulk of spending to Southern California, home to the bulk of the state’s “disadvantaged communities.” This term, as defined by the California Energy Commission, applies to communities that share a preponderance of low-income residents and exposure to high levels of air pollution. Under the CPUC’s final decision, each utility has to spend at least 25 percent of their funds in them.

As the power supplier to the West Coast’s premiere shipping and logistics hub, and the heart of California smog country, SCE has 45 percent of the state’s disadvantaged communities, and 30 percent of its entire customer base qualifies for "DAC" status under the CPUC’s formula. As a result, CPUC’s decision shifted the majority of spending to SCE, while also requiring that it spend the highest proportion of the three utilities — 40 percent — in disadvantaged communities.

Infrastructure is king, but rebates lead the customer charge

Katie Sloan, SCE principal manager of innovation, development and controls, highlighted the DAC part of the program during a press conference this week on the “Charge-Ready Transport” plan. Over the next five years, SCE hopes to see 870 customer charging sites installed, supporting about 8,500 medium- and heavy-duty EVs.

The 40 percent DAC goal will likely involve spending a good portion of the $200 million or so SCE has earmarked for grid infrastructure improvements in the targeted region, she said. The bulk of spending for all three utilities is tied up in spending on “service connection and supply infrastructure to support EV charging.”

As defined by the CPUC, this infrastructure spending involves everything from the distribution circuit to the stub of the EVSE itself, including equipment on the utility side such as transformers and cabling, as well as customer-side improvements such as electrical panels, conduits and wiring.

But as of today, SCE is uncertain just where and how it will be spending that money, Sloan noted. “It will be very customer-specific and depend on how many vehicles they’re adopting, and how often and at what times of the day they’ll be charging.”

Beyond covering the cost of infrastructure up to the chargers, SCE is also spending much of the $52 million earmarked for rebates on DACs, Sloan said. Customers in the approved zones can get almost half of the cost of the EVSE itself, between $5,000 and $15,000, covered by rebates, as long as they aren’t a Fortune 1,000 company, Sloan noted.

That exclusion is in keeping with CPUC’s goal of making sure utilities spend their money only on customers that couldn’t otherwise afford the shift to electrifying their medium- or heavy-duty fleet. Participants also have to buy at least two EVs or convert two fossil-fuel-fired vehicles to electric to earn the incentive.

SCE’s program will also target 25 percent of its spending to ports, warehouses and other logistics centers, and offer the same incentives available to DACs to customers serving electric school buses or transit buses — a prime target for electrification.

“We’re going to have a lot of different things to balance as we put together this program and select customers for participation, hitting the targets for sites and vehicles that the public utilities commission has laid out, and also maintaining our budget,” Sloan said. “That said, we do want to help transform the electric vehicle industry, and that includes making sure customers of all types can participate.”

New rate design: No to demand charges, yes to TOU pricing

Many of the changes incorporated into the CPUC’s final decision were suggested by the "joint parties," a group including Plug-In America, The Greenlining Institute, the Coalition of California Utility Employees, the Sierra Club, the Environmental Defense Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Council.

In terms of aligning the CPUC’s final decision with the group’s goals, “we got most everything we asked for, including the big [Southern California] Edison budget increase,” Max Baumhefner, the NRDC senior attorney who led the group’s efforts, said in an interview last week.

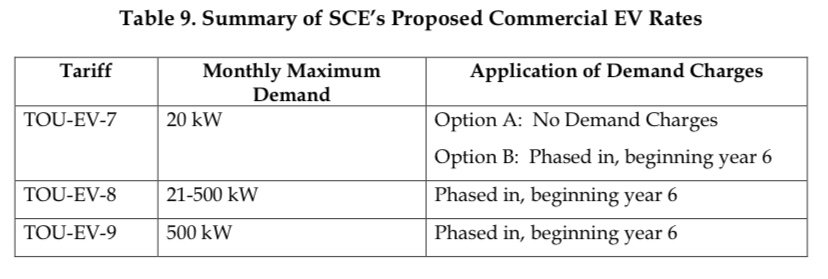

SCE’s plan is also worth following because it could set precedents for how the state’s other utilities design their charging rates, he noted. That’s because SCE’s TOU-EV-7, TOU-EV-8, and TOU-EV-9 rates are the only medium- and heavy-duty rates provisionally approved under the CPUC’s decision, he said. SDG&E’s program was denied, while the CPUC asked PG&E to revise its initially proposed rates and come back in the next few months.

SCE has 90 days to submit its new tariffs to the CPUC, but its proposed rates offer a glimpse into how they’re being designed to incentivize charging during “super-off-peak" hours or at times of high solar power generation, and disincentivize charging during late afternoon and early evening peaks.

And in a unique twist that may well become part of the medium- and heavy-duty charging rates of its fellow utilities, SCE’s program will waive all demand charges — one of the key factors that can blow the cost of hosting a high-speed EV charging system out of the water.

“One of the things we found with early adopters in our service areas, particularly transit buses, was one of the barriers was that when they put load on their systems, they were getting very high demand charges,” SCE’s Sloan said in this week’s conference call. Demand charges are the portion of a customer's bill that accounts for their maximum peak electricity usage, rather than how much they consume over time, as a way to pass on the costs of building and maintaining the grid infrastructure required to meet those peaks.

But today's demand-charge mechanisms are extremely punitive to additional loads like multiple high-voltage EV chargers, which can easily spike a site's usage to twice or more its usual peak when they're all running at once.

“In order to help mitigate that, for the first five years, we do not include demand charges at all. And over the next five years, we fully introduce the demand charges” at a gradual rate of increase, she said.

Erik Takayesu, SCE’s director of grid modernization, planning and technology, added that the utility can’t yet provide an estimate of how much new electricity demand will be brought onto its system by the EV fleets encouraged by its program. That’s because this calculation isn’t as simple as multiplying the typical charging load of 8,500 medium-duty EVs; it requires knowing when and where they're all charging. The same load that could blow up distribution transformers and cause systemwide demand emergencies could also soak up excess solar power on California’s grid, or manage its charging cycles to meet local grid needs.

That’s where SCE is relying on its tariffs and rate structures, demand response opportunities, and complementary technologies such as energy storage to encourage more energy usage during the day when there’s excess capacity, and help overall grid efficiency and reliability, he said. “Locally we may have to upgrade or enhance the grid,” depending on size and location of charging installations, he said. But that’s what the program’s infrastructure dollars are for, after all.

“At the end of the five-year period, demand charges are back, but at a lower level than today,” Sloan said. By then, “we expect in the next five years we’ll have more sophisticated tools for consumers to use,” ranging from software to optimize charging and scheduling of fleet vehicles, to energy storage to help smooth the spikes in grid demand to be expected when several EVs are being charged at once.

“We think this is a key feature of our program, and we’re excited to get those rates available,” she said. SCE will start gathering proposals in the next few months, with a goal of implementing them in early 2019.

Up next: A performance-based, utility-owned residential EV charger pilot for SDG&E?

Not all of the spending approved by the CPUC last week is going to medium- and heavy-duty EV infrastructure. PG&E was awarded $22 million to add 234 DC fast-charging stations for passenger vehicles at 52 sites, while SDG&E won approval for $137 million to install up to 60,000 Level 2 chargers, mostly at multi-family residences.

But SDG&E’s plan to extend its ownership of EV charging infrastructure to “own, install, maintain, and operate” up to 90,000 of the chargers themselves was drastically scaled back in the CPUC’s final decision, which eliminated the utility ownership option altogether.

“Many parties believe SDG&E’s proposed EVSE ownership structure does not meet the Commission’s 'balancing test' that evaluates the benefits of utility ownership and EV charging infrastructure against the competitive limitation that may result from that ownership,” it wrote.

Meanwhile, CPUC’s final decision would require SDG&E to maintain the online marketplace and customer support services required to install the chargers, Baumhefner noted. Those costs would be borne as operational expenses that could no longer be counterbalanced by the capital rate of return it would have earned on the chargers it wanted to own.

The CPUC acknowledges that these changes might make the modified plan unpalatable to SDG&E, and revised the decision to make implementation optional. But it also offered the utility an opportunity to take up an alternative proposed by the group that Baumhefner represents — a performance-based incentive mechanism that would reward the utility for investments that proved cost-effective in the broader marketplace, while holding it financially responsible for investments that failed to compete.

The CPUC didn’t incorporate that proposal, but it did “allow SDG&E to meet and confer with parties to develop a companion incentive mechanism,” under terms described in Appendix B of the decision. The appendix asks the utility to submit plans for a “Reasonable Cost Recovery Mechanism,” one that minimizes costs and maximizes benefits, and can garner the support of at least one ratepayer advocacy group involved in the proceeding.

SDG&E would be able to spend up to10 percent of its total authorized budget on the program, but would have to provide evidence of at least 10,000 EVSE units installed before the incentive mechanism would take effect.

In terms of how SDG&E’s performance might be measured, Baumhefner said his group’s proposal looked at factors including success in deploying the promised number of charging stations, meeting goals for deploying in disadvantaged and low-income communities, delivering lower fuel costs relative to gasoline, and pushing EV load to off-peak hours.

Baumhefner noted that work on that alternative mechanism has been put on a fast track. It also has the support of Siemens, Greenlots and Enel’s eMotorWerks — three of four of the EVSE vendors that have filed comments in the decision. ChargePoint, the well-funded startup with charging station networks across the country, filed comments opposing the plan on anti-competitive grounds.

As for the controversial idea of opening utility ownership of chargers themselves, “if you don’t do something innovative and tweak the regulatory framework like that, utilities will always have an incentive to propose steel in the ground, because that’s what they make their money from,” Baumhefner said. “If you want them to do something else, you have to give them a reason to do it.”