Passenger cars hog the spotlight when it comes to vehicle electrification.

These EVs get center stage at the auto shows and glitzy launch parties. No one is rolling out the red carpet for the humble electric garbage truck.

But while they may not be as captivating to the public, medium- and heavy-duty electric vehicles stand to produce major environmental benefits. Transportation is currently the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Medium- and heavy-duty vehicles account for nearly 25 percent of U.S. transportation emissions, despite making up only 5 percent of all vehicles on the road.

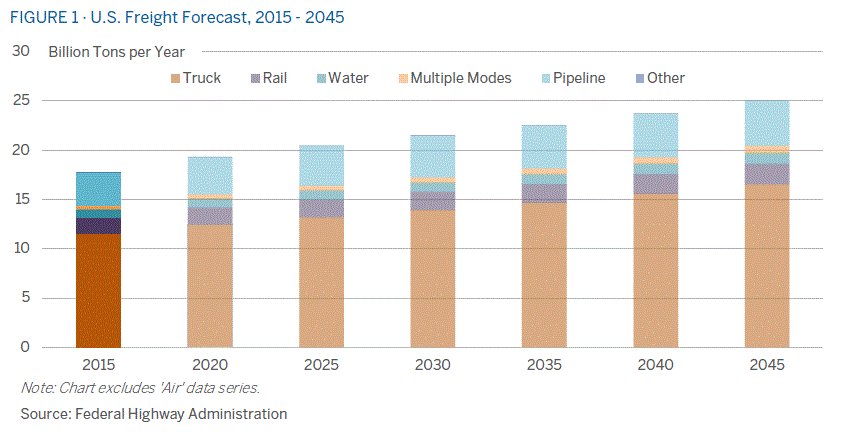

Curbing pollution from trucks and buses will become even more pressing with massive growth in freight deliveries by truck expected in the coming decades. Also, unlike cars, these vehicles operate for up to 40 years, which means that purchasing decisions made today have a long-lasting impact.

Via The Fuse

Electric trucks are coming down the pike, however, to fanfare from key stakeholders.

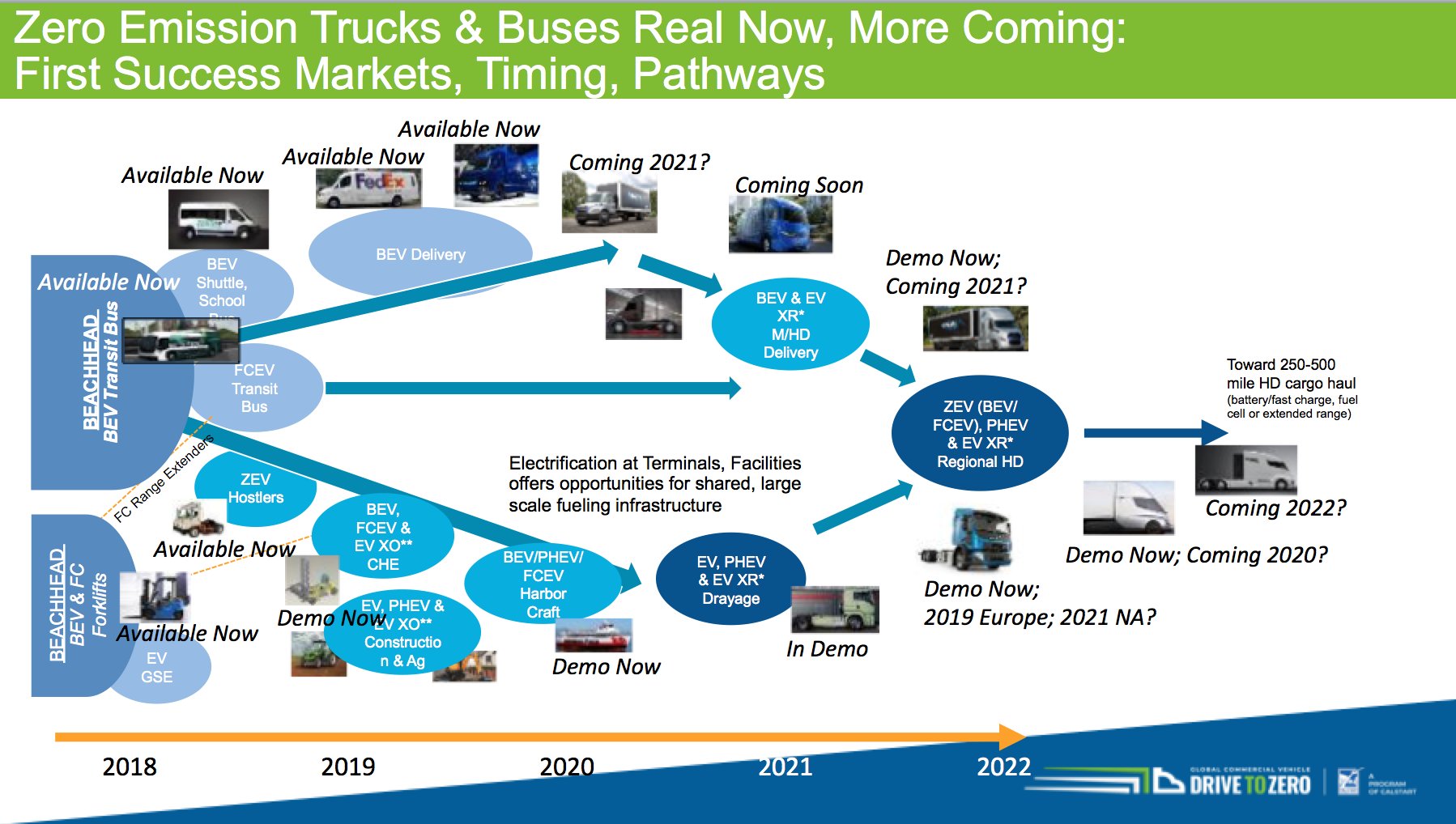

Transportation industry experts have started to coalesce around a roadmap for transitioning medium- and heavy-duty vehicles from petroleum to electricity, based on a combination of factors, including technology availability, fleet needs, policy measures and cost of ownership. A panel of analysts and manufacturers at last month’s EV Roadmap conference in Portland, Oregon agreed that the first phase of growth would be in electric transit buses and urban delivery trucks, with other vehicle models to follow in the coming years.

“You’ve heard tremendous alignment around this exciting space,” said Bill Van Amburg, executive vice president of Calstart, a technology-neutral transportation consortium and nonprofit.

“I’ve been working on this myself for well over a quarter of a century, and I think we’re at the most exciting time for the reality of this technology to start penetration,” he said. “But it’s critical that we do this in the right place at the right time with the right vehicles.”

Other members of the panel, including representatives from Cummins, BYD, Daimler Trucks North America and the Union of Concerned Scientists echoed Van Amburg’s remarks.

“If we had this panel five years ago, we wouldn’t have had Cummins, Daimler and BYD all on the same panel,” Van Amburg said. “The technology has definitely improved and the OEMs definitely see that in urban applications they can deliver something their customers will really like. I think that’s a tremendous breakthrough.”

Phase 1: Transit buses and delivery trucks

“We think there will be phased adoption,” said Julie Furber, vice president of electrified power at Cummins, a century-old engine maker.

The first phase, which is already underway, will see the increasing electrification of transit and school buses, she said. Urban delivery trucks and some commercial marine vehicles are also primed to make the switch, driven largely by air-quality issues in cities.

Those market sectors are also capable of using EV technology as it exists today, said Furber. That typically means the vehicles have a set route where they “return to base” regularly, which creates an opportunity to charge.

They also tend to operate for a total range of under 100 miles per day, so that battery size isn’t a barrier. Finally, the total cost of ownership tends to be lower or there are subsidies available to make the electric platform economically compelling.

Transit buses in particular are leading the way in medium- and heavy-duty vehicle electrification, said Van Amburg.

“The transit bus marketplace is the first core success market where the technology can do the job, meets the duty cycle, and there’s an emerging business model and production capacity,” he said.

Source: Calstart

Samantha Houston with the Union of Concerned Scientists noted that these buses represent a huge opportunity to slash greenhouse gas emissions. She pointed to a 2018 UCS study that found that no matter where it is in the country, a battery electric school bus is 26 percent to 87 percent better in terms of emissions than its diesel counterpart.

As a testament to these benefits and an improving business case, California committed to making all newly purchased buses carbon-free by 2029, as well as to phasing out all diesel and natural-gas buses by 2040.

But despite these early wins, there’s a long way to go before the entire sector gets on board.

Rustam Kocher, electric mobility ecosystem leader at Daimler Trucks North America, said the company is currently focused on making electric local delivery trucks used primarily for food and beverage products. Daimler has also unveiled a medium-duty truck, the Freightliner eM2, and a long-haul truck, the Freightliner eCascadia.

But in general, these larger-format EVs are still limited by range and affordability, he said.

Daimler is putting electric vehicles in the hands of its customers and inviting them to “co-create with us,” said Kocher. But, he added, “We’re not going to try to force what isn’t there.”

Phase 2: Medium-duty and refuse trucks

Medium-duty and drayage trucks for short-haul transport represent the next widely agreed-upon phase in the advancement of medium- and heavy-duty vehicle electrification.

Local distribution vehicles are starting to hit the market with products like Daimler’s eCascadia and Volvo’s FL Electric, but production has been limited because the business case has yet to be proven, according to Van Amburg.

As these short-distance cargo EVs start to see greater adoption over the next few years, they’ll greatly improve urban air quality by eliminating the diesel particulates these vehicles traditionally produced, he added.

Industry players should target this market segment and seek support from cities because of this tangible health and environmental benefit, Van Amburg said.

Fortunately for those industry players, “the technology works best where the greatest need is,” he said.

Listen to our recent episode of Political Climate on urban air pollution.

Refuse trucks are next on the electrification roadmap, although Furber at Cummins said she expects it will take another five to 10 years for these vehicles to reach scale.

Sam Jammal, senior manager of government relations at BYD North America, was a little more bullish. He pointed out that his company has already deployed electric refuse trucks in Palo Alto and Seattle.

The initial business case is similar to buses, he said, where manufacturers are often selling to city agencies, which have a broader set of concerns than their bottom line and shareholders.

“We see refuse as a real opportunity to move the ball forward,” said Jammal. “We’re hoping to see — like on the transit bus side — the complete electrification of fleets.”

Phase 3: Regional and long-haul vehicles

As the total cost of ownership comes down and battery technology improves, industry experts expect to see regional trucks hit the road. According to Van Amburg, these vehicles are still in the demonstration phase, with the first models expected to preview in the 2021 timeframe.

Furber said these types of vehicles are simply “further out.”

The issue for heavy-duty vehicles is battery density. Greater density is needed to move large, heavy vehicles over long distances. But higher density comes at a higher cost and with additional weight. In the trucking world, additional weight is effectively an additional cost, since it reduces the load the vehicle can carry.

“None of our commercial customers want to lose capacity to haul freight or whatever they’re hauling,” said Daimler’s Kocher.

On the positive side, electric vehicle technology is more readily transferable from one vehicle format to another than is conventional vehicle technology, said Van Amburg. Volvo, for instance, used the same electric motor power electronics and battery pack from its buses for certain trucks and off-road equipment. This feature means that the industry can commercialize more rapidly.

“When you look at what’s going on with buses, it’s really paved the way for trucks; we’re an example of that,” said Jammal.

Today’s “technology developments will pave the way for adoption in sectors that are a bit further out,” echoed Furber.

Source: Cummins

But while technology costs are coming down across the board, “the only reason we can get product into customer hands today is because of incentives,” said Kocher. “We don’t see those cost curves coming together for another few years.”

The wait will be even longer for difficult-to-electrify market segments, such as big rigs.

Houston from the Union of Concerned Scientists cautioned that the industry has no time to waste.

“If we don’t start on heavy-duty now, we will undermine our ability to meet our greenhouse gas targets economy-wide,” she said.

“So the urgency is certainly there, which is why we can’t wait to do light-duty first and then heavy. We have to chase both of these things at the same time. And certainly the communities most affected by the pollution share that same sense of urgency.”

A global effort

All of the panelists agreed that transitioning medium- and heavy-duty vehicles from petroleum to electricity requires clear policy signals, such as incentives to reduce upfront costs, deployment targets and perhaps even urban exclusion zones that restrict usage (a model that has been successful in Europe).

The next big task is to build out charging infrastructure with enough scale and capacity to serve growing electric fleets. That also means working with utilities to ensure that the power grid is prepared to meet the increased demand.

Maintaining a pipeline of technology innovation is important, as is supporting fleet managers through the transition and finding ways to de-risk the investment.

This goes beyond the U.S. It will take a global effort to see electric trucks and buses become truly commonplace, said Van Amburg.

“It will take regions all around the world all working concurrently on the same issues, the same types of vehicles, so we can really start to drive supply-chain volumes and start driving down the price."