U.S. greenhouse gas emissions could fall by a record 11 percent in 2020 due to the COVID-19 crisis, according to new analysis, following last year's decline of about 2.8 percent. But as economic activity resumes, emissions are likely to rebound to pre-pandemic levels.

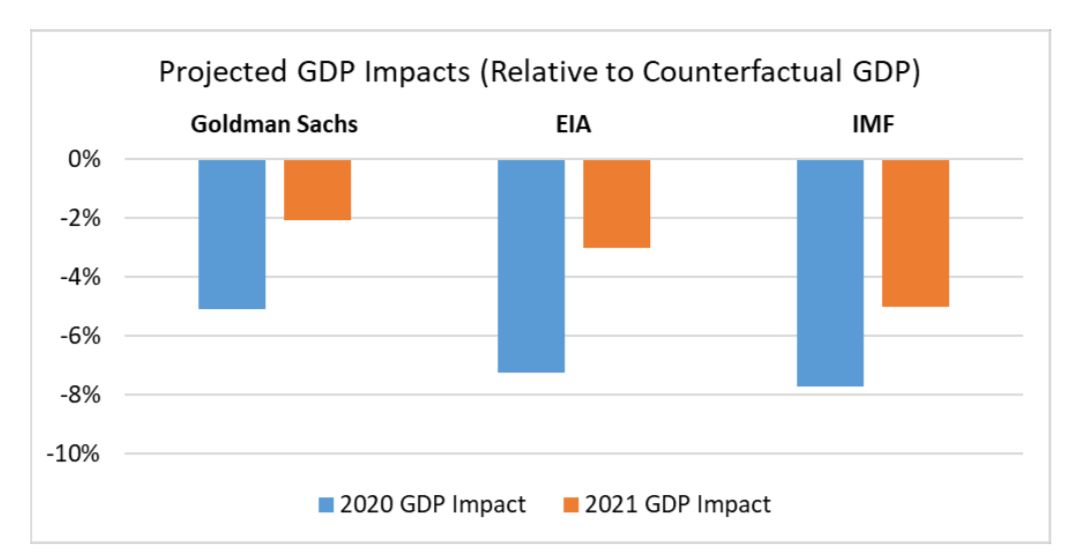

Analyzing estimates of gross domestic product from the Energy Information Administration (EIA), Goldman Sachs and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), energy and climate research organization Energy Innovation found that unprecedented economic contraction in the U.S. may translate to emissions reductions between 7 and 11 percent this year.

Because Goldman Sachs, which presented the most conservative estimate of “GDP shocks” among the group, now appears to be revising its analysis toward greater economic impact, Megan Mahajan, a policy analyst at Energy Innovation who authored the report, said the emissions drop may hew closer to the top end of that spectrum. Depending on how long the crisis lasts, emissions reductions could also exceed that level.

Any cuts are unlikely to last, however.

“One of the biggest unknowns is how energy demand will be impacted with time,” said Mahajan. “The speed of recovery is really going to shape how fast emissions will return to normal.”

EIA: U.S. renewables to overtake coal in 2020

The analysis attributes the biggest decline in 2020 emissions to the transportation sector, as shelter-in-place orders require Americans to stay home and travel less. However, as states reopen, it’s unclear if that trend will hold.

Mahajan acknowledges the trajectory of transportation emissions is “particularly uncertain.” After shutdown orders lift, more residents may use cars rather than public transit in efforts to limit physical contact. Others may avoid travel altogether for extended periods.

The analysis did not model the recent fluctuations in fuel prices. As oil markets crash, it’s undetermined how long those impacts will last and to what extent they will alter electricity prices and generation choices.

“Global oil demand has been doing some strange things lately,” said Mahajan. “Oil prices [and] natural gas prices are going to affect decisions across different sectors on what fuels they’re consuming, particularly in electricity generation.”

The EIA forecasts a 25 percent decline in U.S. coal generation in 2020 driven by low natural gas prices and an overall fall in electricity demand, as some commercial buildings and industrial plants sit idle. Meanwhile, the agency now expects renewable generation to overtake coal for the first time in U.S. history.

Political impetus to decarbonize?

The political response to the coronavirus crisis could also shape emissions trends. Though Energy Innovation expects emissions to rebound as the threat of the coronavirus recedes, clean energy advocates and environmental activists have proposed renewables-focused policies that could extend the environmental impacts of global shutdown orders while boosting the economy.

Fatih Birol, executive director at the International Energy Agency, has said “the historic decline in global emissions is absolutely nothing to cheer,” because of the death and economic downturn associated with the cuts. But he’s also urged countries to put clean energy “at the heart of stimulus plans,” to place the world on track for climate action as economies restart. In April, IEA released research showing an expected 8 percent decline in global emissions in 2020.

Renewables trade groups such as the Solar Energy Industries Association and the American Wind Energy Association have pushed for U.S. lawmakers to include wind and solar tax credit extensions in future stimulus packages. In March, academics and policy experts published a proposal for a $2 trillion “green stimulus” that would continue until U.S. unemployment sinks below 3.5 percent (it neared 15 percent in April) and the economy reaches full decarbonization.

So far, those efforts have been met with minimal support from U.S. lawmakers. While planning a bailout for the oil industry, Republicans have rebuffed any inclusion of support for clean energy in stimulus legislation. This week Democrats unveiled a new $3 trillion stimulus plan without provisions for clean energy technologies.

After the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, the Obama administration included $90 billion in clean energy incentives in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. But emissions still rebounded globally from 2009 to 2010 as countries restarted economies reliant on fossil fuels. EIA has already forecasted a 5 percent increase in U.S. emissions in 2021, while cautioning that estimate may change based on numerous factors.

“If the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis is anything to go by, we are likely to soon see a sharp rebound in emissions as economic conditions improve,” said IEA’s Birol in an April statement. “But governments can learn from that experience.”

Coronavirus may have little lasting impact

Energy Innovation forecasts emissions rebounding after the sharp decline in 2020 and returning to pre-COVID-19 levels “well before 2030,” with little lasting impact on cumulative emissions by midcentury, when scientists say the globe must reach net-zero emissions to stave off the worst impacts of climate change.

Despite the uncertainty, Energy Innovation's analysis gives rough shape to the upper and lower bounds of what U.S. emissions reductions may look like this year and in the near future. Much relies on what happens next.