From food placement in grocery stores to the way Facebook curates newsfeeds, behavioral science is at the core of corporate strategies to maximize sales and engagement.

As understanding of consumer behavior evolves, energy efficiency companies have also become much more sophisticated in how they target their efforts. The so-called behavioral efficiency approach was pioneered by Opower, which based its business model off a 2004 study showing that consumers are more likely to cut energy consumption based on peer pressure ("normative messages") than in response to environmental or economic messages.

"For the last five years, we've been running the largest behavioral science experiment in the world. And it's working," said Opower CEO Alex Laskey in a TED talk from 2013.

Opower has expanded considerably since it was founded in 2007. But that basic premise -- that consumers will consistently reduce energy when compared to their neighbors -- still guides the company's new products.

However, as utilities look for deeper savings beyond the 2 percent reductions that Opower brings, behavioral cues alone are not enough. Real-time pricing information is becoming an increasingly important supplement for efficiency. Notifying consumers about peak pricing changes was the main reason why Opower's behavioral demand response pilot in Baltimore was effective -- people saw the immediate economic opportunity of reducing consumption.

Given this evolution, what does the latest behavioral science tell us about the effectiveness of simple messaging versus economic incentives?

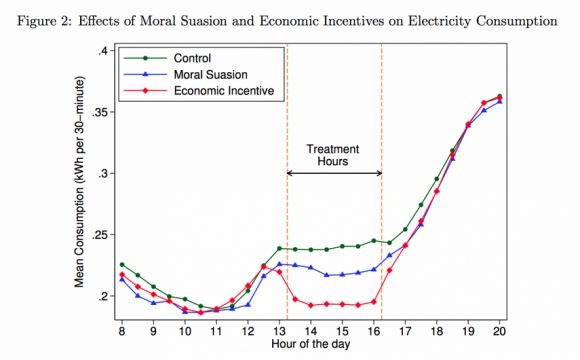

This month, a team of researchers released a study comparing the two different approaches in Japan. They found that moral suasion (i.e., a polite appeal to morality) was an effective way to bring short-term energy savings. However, real-time pricing was a far more effective tool when it came to encouraging long-term changes.

As Japan scrambled to make up for lost nuclear generation after the 2011 Fukushima disaster, energy efficiency turned out to be a very effective tool for closing the gap. In 2012, three researchers from Boston University, Kyoto University and the Graduate Research Institute for Policy Studies started an experiment to explore how consumers were responding to calls to cut electricity consumption.

They gathered nearly 1,700 Japanese homeowners and put them into three groups: a control group that got no messaging; a moral suasion group that was politely asked to cut consumption; and a group that was notified of price surges during peak hours.

Initially, the researchers found that moral suasion worked well. Consumers cut their consumption by more than 8 percent during the first few notifications. But the strategy didn't stick. Consumers quickly stopped responding to the messages, and energy consumption rose to match the control group after three days.

The peak pricing notifications proved far more effective. Consumers with an economic incentive cut energy use between 14 percent and 17 percent. And those savings continued even after those consumers stopped getting notifications about pricing.

'The effect was persistent over repeated interventions. Economic incentives also resulted in a habit formation after we withdrew the treatments," write the researchers.

What does this mean for the way behavioral efficiency programs are designed?

It's not surprising that peak pricing encouraged strong, persistent cuts in energy consumption. Real-world experience in residential and commercial demand response proves it works. However, the study does raise questions about how effective simple behavioral cues are in the long term.

Opower doesn't use moral suasion -- it uses peer pressure. That's an important distinction. According to the 2004 study that helped inform Opower's business model, normative messaging works far better than any other technique.

But this research suggests that behavioral cues alone may not be enough. If utilities and efficiency providers are going to get beyond incremental savings, economic signals will be needed to sustain engagement over time.