Coal plant retirements have become regular news in the United States. In Europe, more than half of all coal plants are now cash flow negative. In India, two-thirds of coal-fired power plants are more expensive than new renewable energy projects.

Regulatory efforts to cut pollution and stiff market competition from renewables and natural gas have tipped coal generation into a structural decline. However, the global coal fleet still has a lot of life left in it.

A significant additional amount of existing coal capacity must come offline in order to cost-effectively meet the Paris Agreement objective of holding global warming below 2 degrees Celsius, according to Managing the Coal Capital Transition, a new report by the Rocky Mountain Institute. In order for those retirements to occur, the authors argue that stakeholders need to gain a greater appreciation of the financial challenges that coal plant owners face.

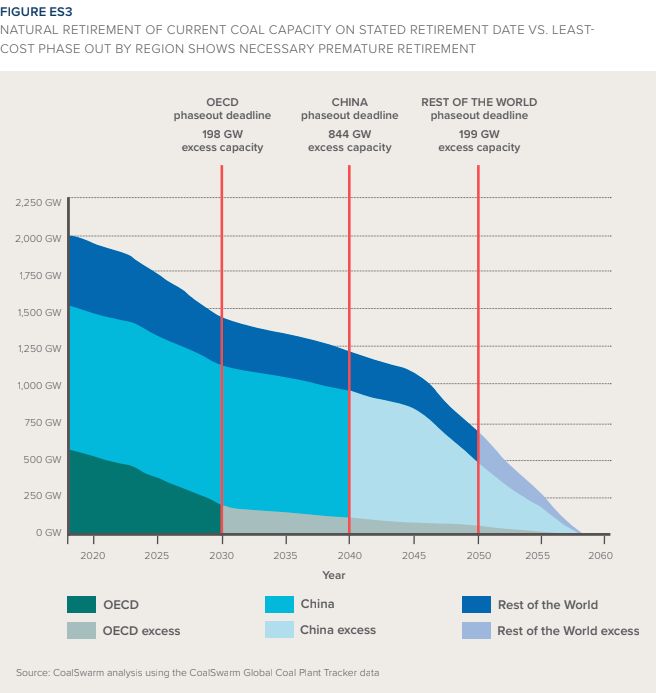

Based on the actual technical lifetimes of the existing coal fleet, keeping temperatures below 2 degrees would require retiring 198 gigawatts of coal in the OECD, 844 gigawatts of coal in China, and 199 gigawatts of coal in the rest of the world. “This holds the potential to strand hundreds of billions of dollars of value globally,” the report states.

The environmental community has put a lot of effort into stopping new coal plants from getting built, said Paul Bodnar, RMI’s managing director of sustainable finance and an author of the report. But while these efforts play a necessary role in curbing future greenhouse gas emissions, they are not sufficient.

The RMI study found that the existing global coal fleet is so large that even if it expired naturally, the power sector would still be far from meeting the Paris climate mitigation goals. Plus, the economic trends pushing coal out of the system in liberalized electricity markets are not necessarily going to determine the outcome in regulated or state-owned electricity markets, like China’s.

“Free-market economics are driving a decline in coal, but it's not driving it fast enough to stay on path for 2 degrees,” said Bodnar. “Therefore, you have to take a good hard look at the global [coal] fleet and say, ‘OK, what is it going to take to accelerate capital turnover?’ Which is what this is really about.”

Adversarial approaches aren't working

A coal asset owner’s financial woes may not seem like an issue that activists and policymakers focused on meeting global climate goals need to concern themselves with. Environmental advocates are engaged on the issue of adjustment costs for labor and communities associated with layoffs, but this problem-solving approach is rarely applied to the coal capital transition.

Bodnar argues that a nuanced understanding of the asset owner’s financial position can shed light on their likely business strategies and political positions, and help other parties position the owner for an amenable exit strategy. Without this understanding, advocates risk slowing down progress, he said.

The potential for major capital losses fuels asset owner opposition to accelerating the energy transition. From their perspective, lobbying against climate and clean energy policy is an “economically rational response to prospective stranding,” the report states. As a result, the energy transition is happening in fits and starts in regions around the world, when the process could be much smoother.

Adversarial approaches to coal plant retirements simply are not working, according to Bodnar. “It isn't working for asset owners, because coal is going down; it isn't working for environmental advocates, because it's not happening fast enough in their perspective; and it's not working from the point of view of policymakers, because they live in fear of these important incumbent constituencies mobilizing to vote them out of office, or quash other climate policies in a drive to minimize the financial effect of early retirement on their balance sheets,” he said.

FirstEnergy’s request for an emergency bailout from the U.S. government for its failing coal and nuclear plants, and the Trump administration’s response, represent prime examples of how the prospect of stranded assets can play out on the policymaking stage.

Despite these efforts, coal generation continues to retire at a rapid pace across the U.S., thanks in part to the success of environmental movements, such as the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign. The problem, said Bodnar, is that these campaigns require huge amounts of time and money. Furthermore, the stakes are much higher abroad where the coal fleet is much younger and owners have more to lose.

The "Asset Position Framework"

So the first step in easing the coal transition is to understand the asset owner’s perspective. That may sound obvious, but Bodnar claims it’s a relatively new concept as an element of climate action.

“Understanding that perspective — just that — is super powerful for regulators and environmental advocates,” said Bodnar. “That allows you to tailor a set of policy solutions that really address proactively this capital loss program, just the same way as people have really started taking seriously the issue of impacts on workers and communities.”

To inform those policy discussions, the RMI report offers an Asset Position Framework with several tactical policy options that vary based on the asset’s current standing. RMI classifies assets into four categories: continuing operator, short-term opportunity, exit opportunity, and wait and see.

In simple terms, a coal-fired asset’s current position is determined by its revenues less its operating expenses, including debt service. Looking further into the future, calculating financial performance includes inputs such as operating expenses and the need for upgrades. In liberalized electricity markets an asset’s financial performance is measured based on shareholder returns. In regulated markets the benchmark is value to ratepayers, particularly in relation to other forms of power generation. Financial performance can also be evaluated based on the owner’s broader portfolio of power generation assets.

The Asset Position Framework categorizes an asset owner’s likely response based on its financial position. Depending on that position, the report describes six potential options from the asset owner’s perspective:

- Continue operations with capital expenditures. Continue operation of plant and make capital expenditures as they are necessary; asset stays on balance sheet, profit and expenses per normal operation

- Continue operations without capital expenditures. Continue operation of plant but avoid large capital requirements; asset stays on balance sheet, profit and expenses per normal operation

- Sell. Make minimal changes to plant and equipment; remove asset from balance sheet; inflows from sale

- Convert. Redeploy existing equipment as feasible and convert facility to natural-gas- or biomass-fired generation; write off equipment that cannot be reused and change asset on balance sheet

- Idle/mothball. Cease plant operations but maintain equipment to potentially restore service in the future; keep asset on balance sheet but forgo operating revenues

- Decommission. Fully cease plant operations and tear down to brownfield; write off any outstanding balance or negotiate with regulators for some level of continued recovery

Bodnar noted there is an interesting wrinkle with respect to the “sell” option. In some cases, companies that own both coal mining and coal power assets are perfectly aware that their business is in trouble and want to get out, but they need to make the business look appealing in order to do that.

“The need to sell the asset to someone else requires keeping up the front that everything's going to be OK,” he said. “Because otherwise, who's going to buy it?”

So if an owner’s only option is to sell, company leadership could be well aware of coal’s decline but vehemently defend the industry in public in order to try and make a graceful exit.

10 policy options

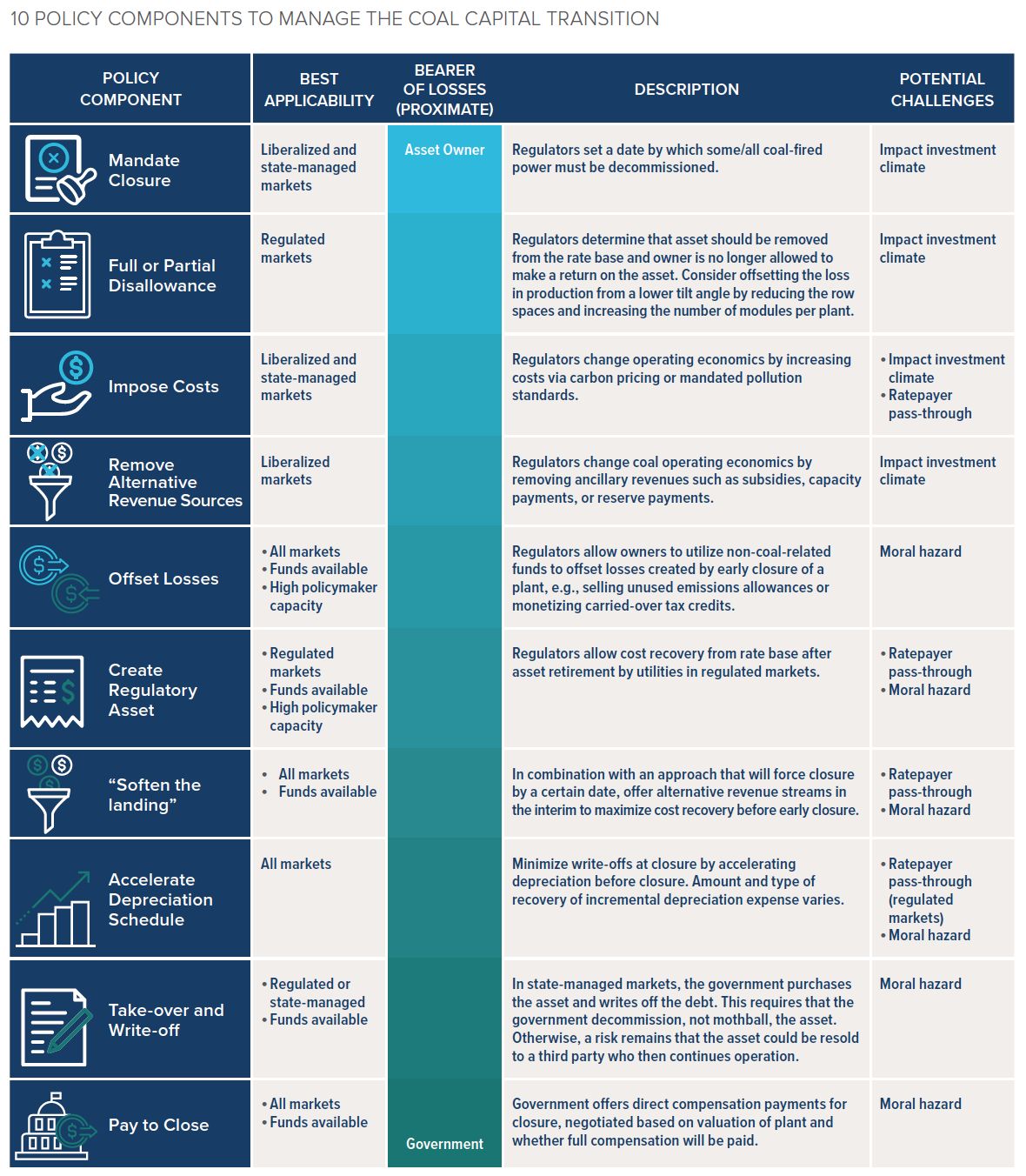

From the policymaker’s perspective, there’s a separate set of options to consider. These options are based on factors such as: the type of power market they’re based in, how much authority they have and the overall investment climate in their jurisdiction. Stemming from that, the RMI report describes 10 policy actions for managing the capital losses from the early retirement of coal-fired generating assets.

Options range from mandating coal plant closures, to removing ancillary revenues from coal plants, to helping offset the asset-owner’s losses, to directly compensating the asset owner for the plant closure.

Some of these policy responses have already been put into action. The Finnish government, for instance, has taken the mandate approach, while the Canadian province of Alberta took a different tack.

In 2015, the Alberta government announced a Climate Leadership Plan that called for all coal-fired electricity to be phased out by 2030. Roughly half of the province’s energy generation comes from coal today. Twelve of the province’s 18 coal-fired generating units were already slated for retirement at the time the plan was announced. To address the remaining six plants, Alberta policymakers offered to give the three asset owners “transition payments” totaling more than $1 billion to ensure the coal units came offline by the 2030 deadline. The bilateral deal, made possible by specific factors in region, represents a success for this kind of solution.

The outcome in Australia was different. In 2011, the government attempted to negotiate the premature closure of several coal plants by offering payments to the owners. But the deal failed when policymakers and asset owners couldn’t agree on the value of the coal assets.

Fighting harder is one way stakeholders can try to speed up the retirement of coal plants, said Bodnar. Removing the roadblocks is another, which he argues is preferable.

“[S]tranding these assets is not and should not be the goal; the loss of value associated with stranded assets is an undesirable consequence that, while to some extent inevitable, should be actively mitigated to ensure that all stakeholders are on board with the direction of the energy transition,” the report concludes. “Instead, policymakers have an opportunity to understand and implement a new toolkit to spur faster energy transition through dialogue rather than adversarial approaches.”