General Electric’s latest turbine release reaffirms the wind industry’s leading trend: the bigger the turbine, the better.

On Tuesday the company unveiled its 4.8-megawatt turbine, with a rotor diameter of 158 meters, the length of a Boeing 747. The turbine will be among the largest on the market, but likely not for long.

“This is a much larger turbine than what’s typically out there,” said Aaron Barr, a senior consultant with MAKE Consulting. “This new class of 4-megawatt turbines has really just hit the market over the last year-and-a-half, and they’re so new that very few of them have been prototyped to date, but every turbine manufacturer is rushing toward this space.”

The play by GE could make the manufacturer more competitive in the European market, where limited and expensive space for wind farms means bigger turbines are advantageous.

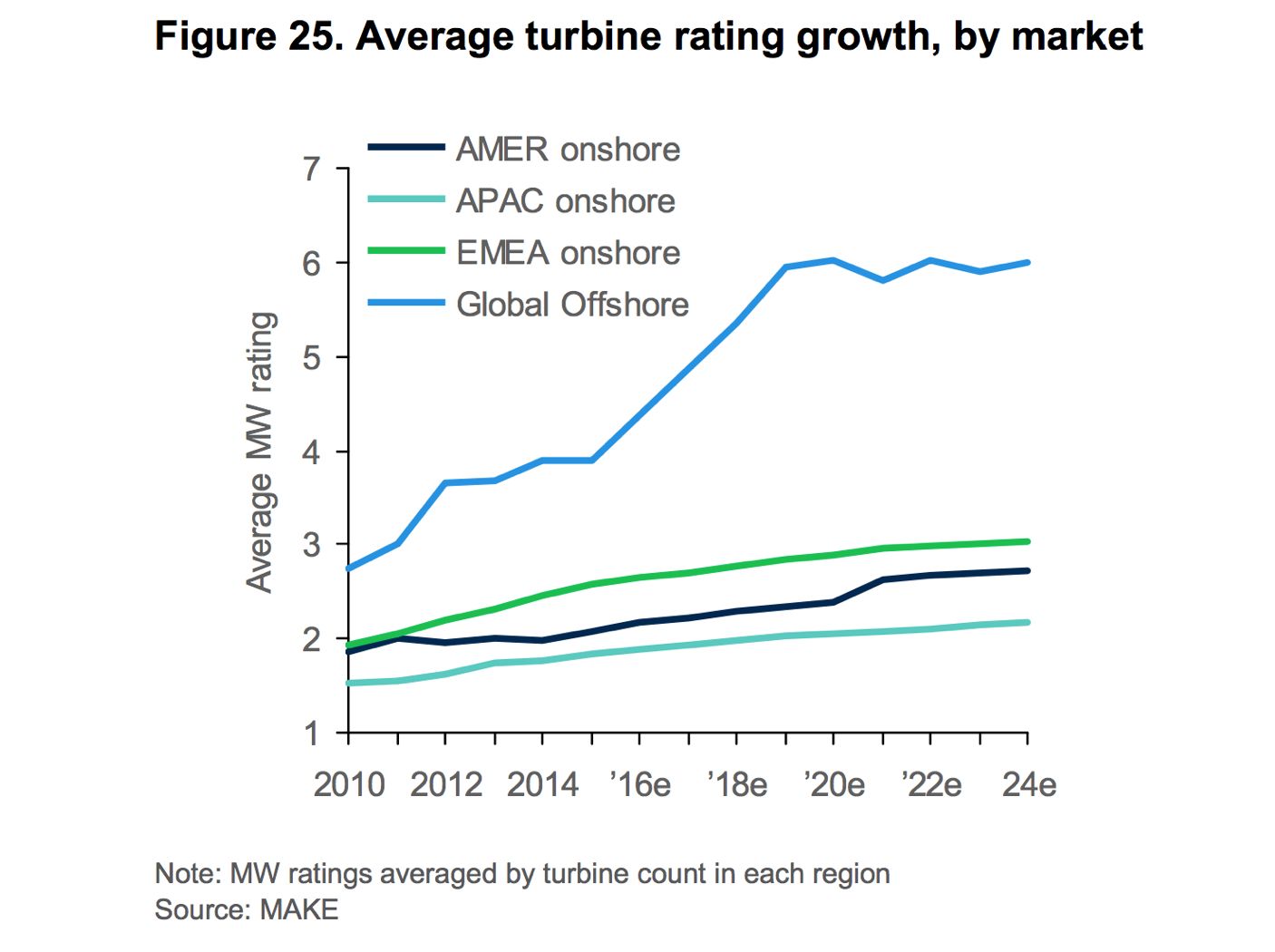

As shown in the chart below from MAKE's global trends report, the European market’s average turbine is expected to climb past 3 megawatts by 2024.

“The European market is quickly racing toward this 4-megawatt installment,” said Barr. “This move to introduce the new larger turbine size is clearly aimed at trying to increase their market share in the European market.”

According to MAKE, GE ranked second in the world for onshore wind in 2016, with 12.7 percent market share. But GE held only 8 percent of market share in Europe, coming in sixth place. Barr said about 80 to 90 percent of GE’s current onshore installs are in the 2-megawatt class. With this innovation, the company could change that.

The announcement comes on the first day of the HUSUM Wind conference in Hamburg, where MAKE expects other platform announcements from competitors like Nordex and Intercon. All are hoping for a larger slice of the blossoming wind market in Europe.

While GE’s new turbine represents a bold move forward for the manufacturer, it also speaks to larger forces at work in the onshore wind industry that are especially observable in Europe.

As turbines get bigger and blades get longer, turbines can produce more energy at lower costs. An August report from MAKE showed turbine sizes steadily climbing globally.

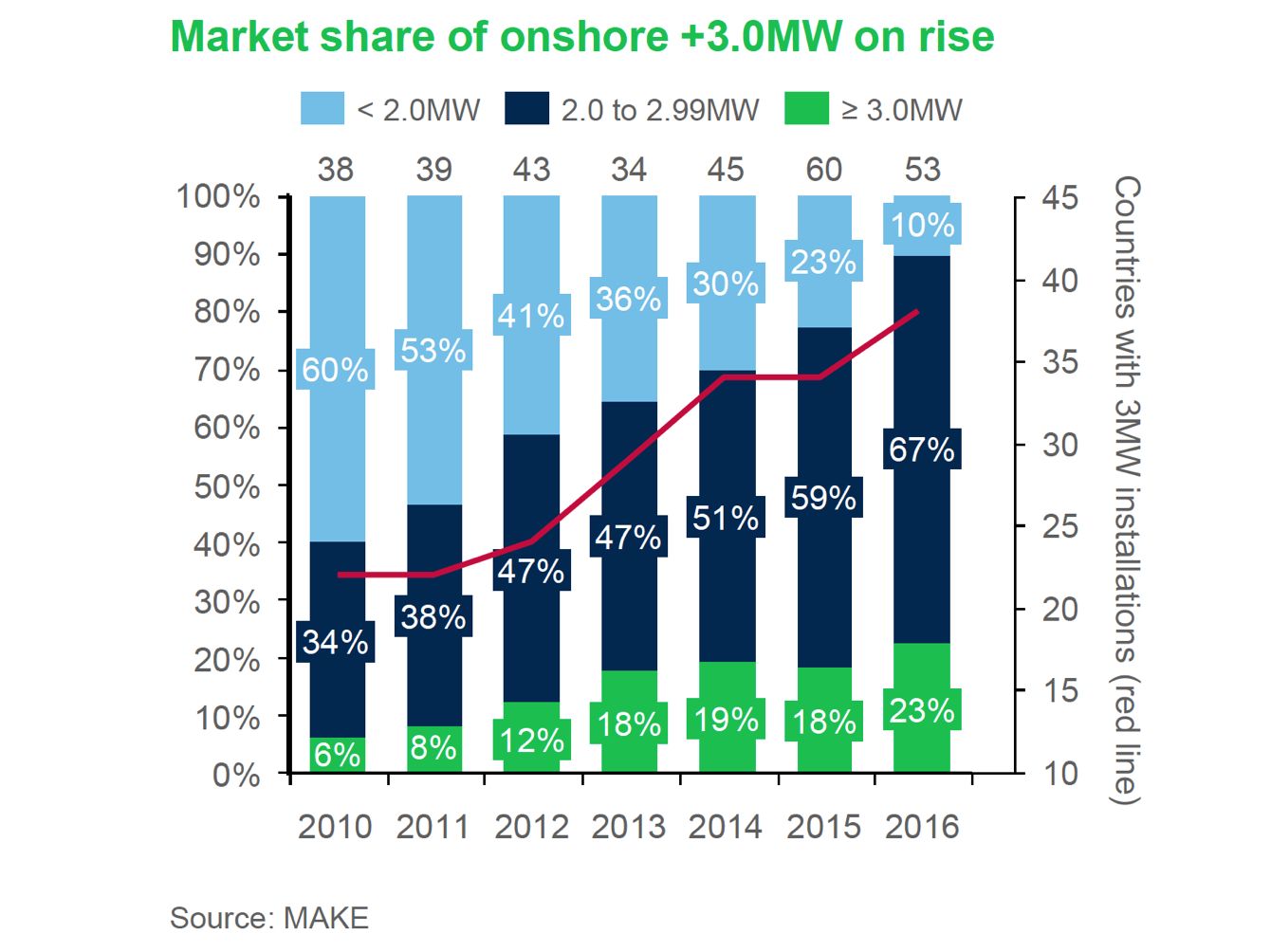

In 2010, 40 percent of onshore turbines were 2 megawatts or more. In 2016, that figure reached 90 percent.

While the growth is more pronounced in Europe, economies of scale mean bigger turbines will also gain in popularity in markets with plentiful, windy space like the United States and Latin America.

According to Barr and several members of GE’s onshore team, the innovations are all geared toward achieving the lowest levelized cost of energy (LCOE). “That’s the whole name of the game,” said Barr. “You want to maximize the output of every turbine. By doing so, they’re able to limit the LCOE and also generate a lot more energy per turbine.”

While GE has not yet disclosed pricing details, the release of this turbine puts LCOE front and center. “The LCOE race never ends, but our mission is to get out front and stay out front,” said Pete McCabe, GE’s president and CEO of onshore wind business. “This technology will do it.”

The company is now making final decisions on design and production logistics (which presents challenges because the blades are so large), as well as European locations for a prototype install. That installation will be complete before the end of next year. The turbine will be on the market for customers by the end of 2019.