The U.S. electric grid is not crumbling. The regulatory structure that supports it, however, is showing its age. Those are just two of the findings from a new study about the electric grid published by the Massachusetts Institute for Technology.

There are problems with regulation, and therefore with pricing structure. There are also significant issues with rules for building transmission, cybersecurity and general oversight, according to the study’s authors.

And yet, the grid can be fixed, they say -- under the umbrella of federal oversight with clear directives and new pricing schemes.

To meet modern electric needs, the authors argue that the system of paying for power distribution is broken. Less than 100 hours in the year account for 10 percent to 18 percent of capacity needs in North America. And yet the vast majority of electric customers in the U.S. pay a flat fee.

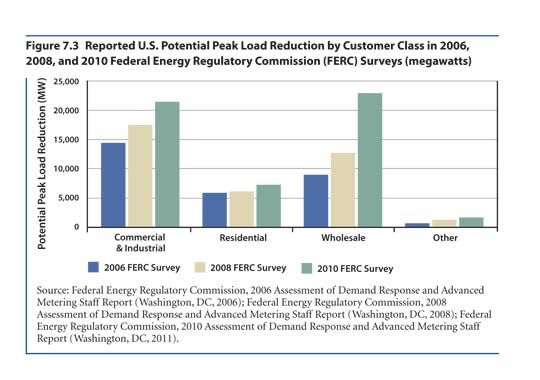

The ratio of peak demand to average demand is only increasing, which requires new ways to pay. The authors estimate that dynamic pricing, which is common for commercial and industrial customers, will become widespread and likely even the default for residential consumers by 2030.

Dynamic pricing requires advanced metering to measure small time intervals. However, even though millions of meters have been installed in the U.S., there is only a small appetite for residential dynamic pricing, and no default dynamic pricing for residents outside of Ontario. As peak continues to increase and legacy meters get to the end of their life, the authors estimate that most utilities will turn to digital meters.

But putting in meters is just one step towards dynamic pricing. There is public outcry that different prices at different times will hurt people -- especially the elderly and the poor. But studies have found that is not necessarily true in well-designed plans, especially because those groups tend to have smaller peaks to begin with.

However, as rates continue to increase to pay for new peaking generation, something will have to give. That something is how the price of electricity is calculated.

Not only do flat rates need to go the way of the dodo, but the authors also argue that fixed network costs should be recovered through non-volumetric charges. Essentially, distribution charges shouldn't be charged per kilowatt-hour. Currently, if someone puts in solar panels, he will save on energy charges and the distribution charge, although the utility still needs to invest in the distribution system, and if there is a lot of distributed generation, the utility may even need to invest more in distribution automation to meet the load on the circuit.

Pricing was only one area of recommendation from the interdisciplinary study. Other recommendations include:

- New legislation should grant FERC enhanced siting authority for major transmission facilities that cross state boundaries or federal lands.

- The federal government should designate a single agency to have responsibility for working with industry and to have the appropriate regulatory authority to enhance cybersecurity preparedness, response, and recovery across the electric power sector, including both bulk power and distribution systems.

- More research is needed, including the development of computational tools that will exploit the potential of new hardware to improve monitoring and control of the bulk power system; methods for wide-area transmission planning; processes for response to and recovery from cyberattacks; and understanding of consumer response to alternative pricing/response automation systems.

- State regulators and others supervising distribution utilities should require utilities to compile and publish standardized metrics of utility cost, reliability, and other dimensions of performance.

The authors pointed to a 2011 EPRI report that estimated that $3.7 billion is needed for grid cybersecurity, a relative drop in the bucket compared to other grid-related investment. Also, a cyber attack is not a matter of if, but when. To meet cybersecurity requirements, new legislation should look towards FERC and the Department of Energy or the Department of Homeland Security to oversee grid security.

Some of the recommendations are already happening. FERC Order. No. 1000 will increase wide area planning of transmission systems; California already has metrics to measure the smart grid plans of its three large, investor-owned utilities, and the DOE is collecting data on stimulus grant projects, including dynamic pricing pilots. But widespread changes will require federal guidance, and in some cases, mandates.

“We are encouraged by recent levels of awareness, concern and, in some key areas, action,” the authors wrote. “But the journey to the electric grid of 2030 has begun, and there will be plenty of surprises along the way. As this study indicates, much can and should be done now to smooth the potentially very bumpy road ahead.”