Never-fail military microgrids are breaking new ground in distributed energy management. Now one of them is getting connected to the grid at large.

That’s the news from Fort Bliss, Texas, where the U.S. Army and Lockheed Martin cut the symbolic ribbon Thursday on the first Department of Defense grid-tied microgrid. The project, started in 2010, uses renewable energy (a 120-kilowatt solar array) and energy storage (a 300-kilowatt battery system), as well as the base’s existing backup generators, and ties it into a miniature grid via Lockheed’s Intelligent Microgrid Control System.

It’s not the first DOD project to combine on-site power resources like solar, batteries and backup generators into a self-sustaining, islanded grid unit -- in other words, a microgrid. In fact, the military is leading the charge in microgrids, given its need for fail-safe, always-on electricity supply, particularly when the bigger grid blacks out, no matter what the cost.

But Fort Bliss is the first Army microgrid project to hook itself up to the utility grid, which opens a new realm of possibilities, as well as challenges, for the system. That’s because, while the Fort Bliss microgrid is helping the Army meet its carbon footprint reduction and efficiency goals, its core purpose -- or “tactical utility,” as Fort Bliss spokesman Major Joe Buccino said in Thursday’s release, “is its ability to allow us to operate off the grid.”

“We are entering an age of emerging threats and cyberwarfare,” Buccino said. “We are assuming an unacceptable measure of risk at fixed installations of extended power loss in the event of an attack on the fragile electric grid." In other words, energy security comes first when it comes to the Army and the utility working together.

Microgrids: Islanded Today, Dynamic Tomorrow?

While the Army hasn’t disclosed how much power Fort Bliss uses, it’s no doubt much greater than the relatively small amounts coming from its 120-kilowatt solar system. While the Army is investing billions into solar and other renewable energy projects and recently announced a plan to build a 20-megawatt, $120 million solar PV plant at Fort Bliss in partnership with local utility El Paso Electric, its microgrid is still mostly powered by backup generators.

Likewise, the 300-kilowatt energy storage system is likely too small to back up the Army’s Brigade Combat Team complex where it’s installed, though the partners do say it’s “critical in lowering cost and maintaining a steady stream of energy,” as well as being able to respond to periods of high energy demand and cost to shave the base’s needs.

So-called “islanded” microgrids, or those built just to power themselves independently of the grid, are still a vital asset for their owners. The Food and Drug Administration’s White Oak research facility in Maryland kept itself running during Hurricane Sandy with its always-on microgrid system built by Honeywell, for example.

Data centers, hospitals, airports and other critical sites often have backup generators and uninterruptible power systems that can do the trick of a microgrid during emergencies. Likewise, in developing countries like India, Brazil and South Africa, where grid power is unreliable and blackouts are a daily occurrence, many businesses have their own power supplies.

But most of these systems aren’t set up to interact with the grid when it’s still running. That’s too bad -- because the real benefits of microgrids to the grid aren’t simply tied to how much power they can supply themselves. More important is how they could interact with the grid as a dynamic resource, to do things like ease congestion, reduce peak demand or respond to grid emergencies.

That’s the potential that has many industry watchers predicting a surge in microgrid investment, though those predictions have a lot of variation in them, with forecasts ranging from $19 billion to $40 billion by 2020. Pike Research estimates there are 400 projects globally, but that includes plans that are still only on paper at this point.

GTM Research sees more short-term opportunity for islanded microgrids, or those that aren’t built to interact with the grid. But in the longer term, “dynamic islanding will provide the biggest opportunity” for these systems to justify themselves on economic terms.

Building economically feasible, grid-interactive microgrids is harder than it sounds, however, with both technical and regulatory hurdles to overcome. Still, we’ve seen a few projects aimed at making it happen. The Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) has built a $14 million microgrid, including renewables and flow batteries, with S&C Electric Co., for example. The University of California at San Diego has built a cutting-edge microgrid that supplies 90 percent of the campus’s power needs, and is being integrated into a larger microgrid project with utility San Diego Gas & Electric.

The Military Leading the Microgrid Charge

Breaking down the barriers between microgrids and utilities could open up a new world of opportunities for backup power systems to earn money when they’re not being used for emergencies -- in other words, almost all the time. The technical challenges of tying all these local grid assets together is the realm of big players like General Electric, ABB, Siemens, SAIC, Schneider Electric, Boeing, Honeywell and Lockheed, as well as smaller specialty technology firms such as Spirae, Integral Analytics and Power Analytics (formerly EDSA).

In the meantime, there’s a push into technology that helps connect microgrid capabilities to the demands of grid operations and energy markets, with players including the aforementioned giants, as well as startups like Blue Pillar, Viridity Energy, Powerit Solutions, Enbala and many others.

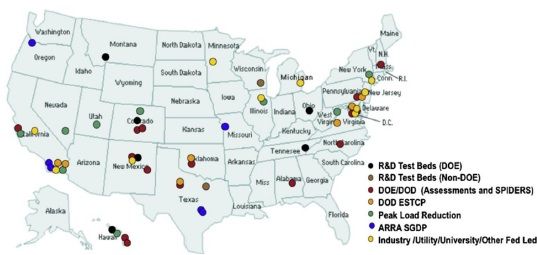

But the biggest driver of microgrids into the real world may well be the U.S. military. GTM Research has collected some data from DOD’s microgrid programs, which include interest and “prioritization” of research and development into inverters and switching, control and protection technologies, as well as the system design, integration and economic analysis tools that make them useful to their owners.

DOD and the Department of Energy are also working on standardizing the technologies that go into microgrids, via the Smart Power Infrastructure Demonstration for Energy Reliability and Security (SPIDERS) projects underway at Fort Carson, Colo. and at Pearl Harbor-Hickam Air Force Base and Camp Smith in Hawaii. Military microgrid developers include SAIC, Lockheed Martin, Power Analytics (formerly EDSA) and General Electric, which is already in a big microgrid project with the U.S. Marine Corps.

Jim Gribschaw, director of energy programs at Lockheed Martin, noted in Thursday’s release that DOD’s work could lay the technical and regulatory ground work for moving microgrid technologies for hospitals, universities, commercial businesses and industrial sites, to name a few potential customers of the “energy-efficient and secure future” it’s promising out of the technology.

GTM Research predicts that North America will be the earliest adopter of microgrid technologies, with resiliency, reliability and regulatory factors seen as key drivers. One key development is the new IEEE 1547.4 standard released in 2011, which covers the design and integration of microgrids into electrical power systems in a way that wasn’t permitted by previous standards.

At the same time, microgrids are popping up around the globe. The EU MORE MICROGRIDS Project has eight pilots underway led by a consortium of vendors, power distribution utilities and research teams from 12 European nations, and Japanese firms and organizations have nine microgrid projects ranging from 300 kilowatts in Albuquerque, New Mexico to 50 megawatts for the Miyako Island Microgrid, to name two noteworthy examples.