In recent years, corporate demand has accounted for a significant portion of the large-scale solar pipeline: 19 percent of procurement in 2019 and 21 percent in 2018. Only renewable portfolio standards and procurement compelled by economics accounted for more solar purchases in the last couple of years.

Corporate solar demand and pledged emissions reductions have made businesses — alongside states setting 100 percent renewable portfolio standards — the de facto leaders on climate policy in the United States.

Still, the actions those corporations are taking are not nearly ambitious or rapid enough. The U.S. is currently on track to cut emissions 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, leaving the country short of the 26 percent reduction it pledged as part of the Paris Agreement. And the pledges made by participating nations as part of that pact were designed to increase in scale and ambition over time, not decrease.

Though much of the decline in emissions the U.S. is expected to achieve over that timeframe has been effected by sub-national governments and companies, “there’s a gap,” said Andrew Light, a former State Department climate envoy and now a professor at George Mason University, speaking with National Public Radio in September.

Short of a total rework of the U.S. economy, closing that gap will require actions from companies big and small, with solar expected to account for a significant portion of those commitments.

The rise of the corporate renewables buyer

In terms of the scope of corporate renewables procurement, large technology companies have no rival.

Tracking from the Renewable Energy Buyers Alliance shows Facebook procuring the highest capacity of U.S. renewables in 2018 and 2019. In 2017, Google took that title.

Worldwide, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Google signed contracts for the most renewables capacity last year. Google inked more than 2.7 gigawatts of clean energy deals in 2019 — a year when the tech company announced nearly 2 gigawatts of contracts at one time, calling it the largest corporate announcement to date. Trailing Google in 2019 was Facebook, followed by Amazon and then Microsoft.

In solar alone, companies procured nearly 1.3 gigawatts in 2019, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association. Apple and Amazon purchased the most solar last year, while Google, Facebook and data center and cloud company Switch ranked in the top 10 corporate buyers.

Overall, corporate “buyers are reshaping power markets and the business models of energy companies around the world,” said Jonas Rooze, an analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, in January.

In the United States, Google has joined regional transmission organizations and negotiated the creation of a green-source rider program in North Carolina.

But that level of influence is only available to a select few corporate buyers.

Looking down a few notches

Others have worked to come up with solutions that allow companies with smaller footprints to access renewable markets as well.

Renewable energy marketplace LevelTen Energy, for instance, has helped Starbucks procure partial shares from a group of renewables projects and aggregated demand from companies such as Salesforce and Bloomberg, allowing them to sign offtake agreements for a share of just 5 to 10 megawatts of a larger solar project.

Clearloop, a startup launched in 2019 and co-founded by former Tennessee Governor Phil Bredesen, has recently proposed another option: letting companies pay upfront into solar projects, matching generation to their carbon footprint. That treats solar as a carbon offset, a controversial concept but one that both Google and Facebook use in their sustainability goals.

Laura Zapata, one of the company’s founders, says Clearloop advocates for companies to prioritize direct carbon-footprint reductions, with Clearloop offsetting any remainder.

Like LevelTen, Clearloop hopes to target what it views as a persistent issue in corporate renewables: power-purchase agreements and financing are only available to certain companies, and projects are mostly deployed in markets with favorable regulations or policies. Zapata said the solar that Clearloop builds is meant for companies that can’t or won’t sign long-term power-purchase agreements or that don’t want to build in wholesale markets.

“PPAs are good, but they’re not going to be enough for us to decarbonize at scale,” said Zapata. “How can we make it easier for more companies to be able to invest?”

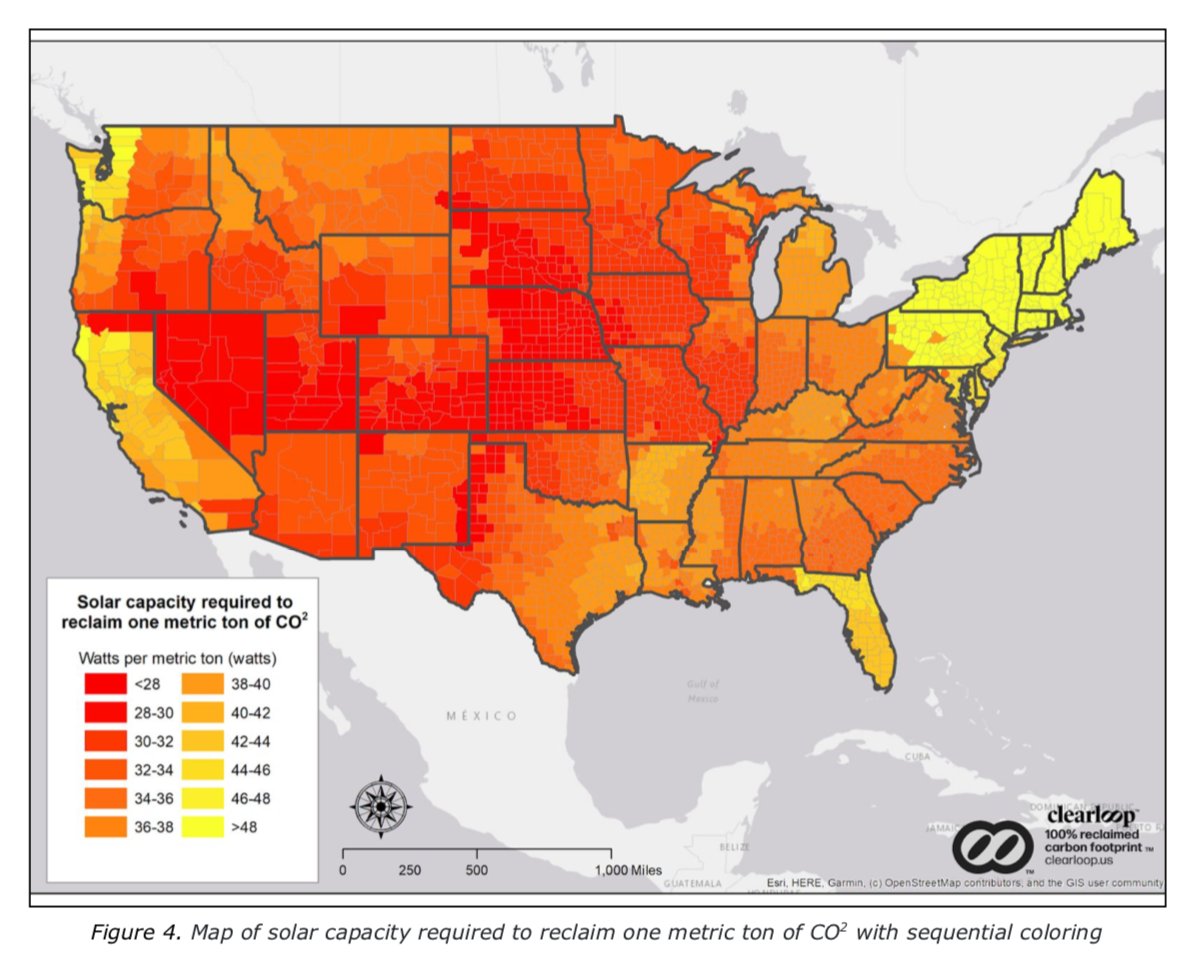

Clearloop is focused on the Southeast and is working on its first 1 MW project with developer Silicon Ranch, which Gov. Bredesen also helped found. Zapata says every solar project in that region has the potential for greater climate impact because the region’s grid relies on higher proportions of fossil fuels than in other areas of the country, such as California or the Northeast.

Virginia and North Carolina have attracted significant corporate solar deals in recent years, as big tech companies work to take advantage of cheap power prices to run their data centers. But those projects have been most available to large players. While Virginia’s Dominion Energy has faced intense pressure to allow corporations to buy more renewables, it has signed specifically tailored solar deals with Facebook (this year Dominion also pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, just before Virginia advanced legislation setting out a 100 percent renewable energy goal). And as noted above, Google was able to coax Duke into setting up a green tariff (last year Duke also committed to zeroing out carbon emissions by midcentury).

If private corporations are to make a bigger impact, Zapata argues that companies will have to think about where they’re installing solar projects to maximize emissions reductions. And smaller companies will also have to play a role, while also coping with the policy strictures that make solar difficult to build in certain geographies.

“There are only so many Googles in the world,” said Colin Smith, a senior solar analyst at Wood Mackenzie. “The growth of demand for renewables from smaller companies that aren’t tech giants is growing fast.”

In the absence of federal climate policy, large companies have significant work ahead, too. Even for renewables buyers with political clout, greening the grid is difficult.

In September, Google pledged to supply all of its electricity with renewables at all times of day and night by 2030. Its progress toward that goal is divided along geographic lines: An analysis of its 2019 electricity consumption showed carbon-free sources accounting for a majority of power running data centers in windy states like Oklahoma, while renewables supplied an average of only 55 percent of power for data centers in Tennessee and just 19 percent in South Carolina.

And though Google has for years zeroed out its Scope 1 and 2 emissions (those that come from its direct activities or purchased energy), the digital behemoth is still tackling Scope 3. That scope, which encompasses indirect emissions associated with its activities such as travel and manufacturing, makes up the great majority of Google's overall emissions. It's the trickiest segment for most corporates to grapple with, but it must be tackled in order to close the emissions gap.