The grid edge is a complex place (and we have the graphic to prove it).

The grid edge is where utilities, consumers and an ecosystem of technologies — from smart thermostats and solar to electric vehicles and energy storage — all intersect and are creating new markets and business models in the process.

Policy is changing too. In many ways, policy is actually making the grid edge transformation possible.

Earlier this week, GTM’s Jeff St. John led a fantastic interactive roundtable discussion for Squared members about the evolution of distributed energy at the edge. As our resident state-level policy wonk, I contributed a list of relevant policy developments. Here is that list, along with some additional insights gleaned from the roundtable discussion.

Different kinds of "grid mod"

First, why do we care about the grid edge?

As Jeff St. John described it, it’s all about “the technology, regulatory and business model innovations aimed at achieving a clean-powered, affordable, reliable and equitably shared grid edge, one that allows distributed energy resources — and more specifically, customer and third-party-owned and operated DERs — to play their optimal role in solving the world’s energy and climate challenges.”

Utilities have been and are making significant investments in the underlying technologies to enable this grid edge transformation. But investments in traditional infrastructure still far outweigh their spending on grid modernization. Some utilities are trying to get approval for traditional investments while passing the plan off as “grid mod.” But so far, regulators aren’t going for it.

In Duke Energy’s case, North Carolina stakeholders pushed to cut billions of dollars in undergrounding investments from the plan, and put greater emphasis on renewables, storage and conservation voltage reduction instead. But even in its trimmed-down version, regulators rejected the grid modernization bid, citing a failure to convincingly justify the costs.

On the other end of the grid investment spectrum, there are non-wires alternatives, or NWAs. These are the projects that allow utilities to invest in — and, importantly, recoup some form of return on investment from — distributed energy resources as an alternative to traditional copper and steel. NWAs are intended to be just as, if not more, reliable than the infrastructure they’re replacing. They’re also viewed as a very important future source of value for DERs.

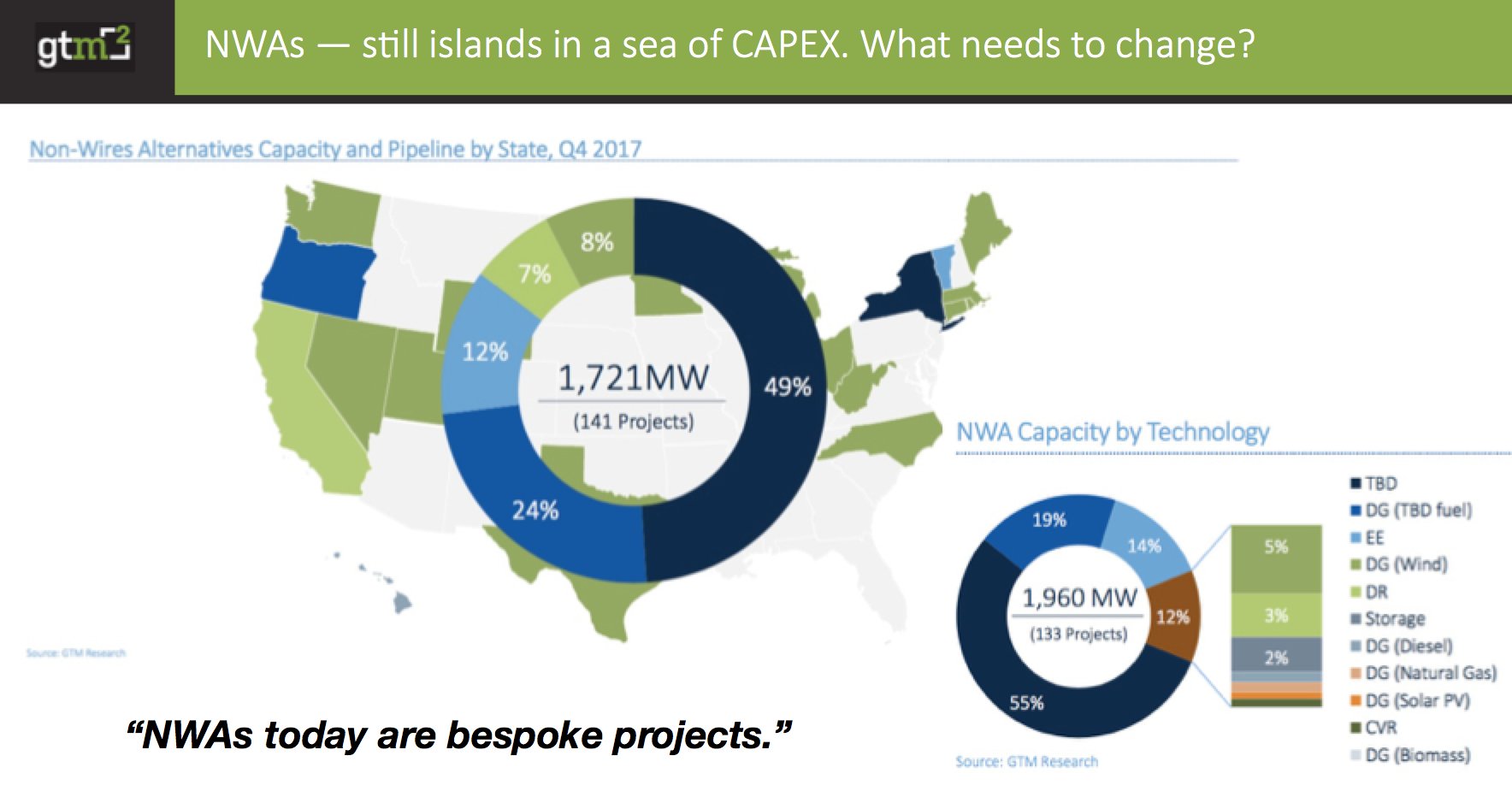

However, as Jeff St. John discussed, NWAs are really only happening in a handful of states. And of the 141 projects tracked by GTM Research, half of them are in New York.

A rundown of non-wires alternative programs

Arguably the most widely known project is Con Ed’s Brooklyn-Queens Demand Management initiative, which is deferring $1 billion in substation upgrades with roughly half that much spending in efficiency, demand response and some distributed energy storage.

Vermont was one of the first states to open the NWA market when regulators allowed Green Mountain Power to offer its customers monthly payment plans for Nest thermostats, Tesla Powerwall batteries, smart water heaters, and grid-responsive EV chargers to help it shave peak loads and defer capacity costs.

In California, NWAs mostly consist either of batteries utilities have installed under the state’s energy storage mandate, or DERs gathered to solve emergencies that might not have been solvable with a “wires” solution. For instance, Southern California Edison contracted for 50 megawatts of batteries and 50 megawatts of Nest thermostat-enabled demand response in a matter of months to help cover for the loss of the Aliso Canyon natural-gas storage facility last year.

There’s also the 125 megawatts of DERs that SCE has contracted for its Preferred Resources Pilot — a program that has faced long delays and was nearly canceled, until California regulators rescued it at the last minute. As Jeff St. John wrote in a recent article, the PRP projects are “aimed at bridging the gap between experimental and full-scale rollout of distributed energy resources as a grid resource.”

Oregon is another state of note, where the federal Bonneville Power Administration launched one of the first NWA projects aimed primarily transmission grid investment deferral.

Back in 2015, National Grid executed on a non-wires alternative project to meet load growth in Rhode Island, in response to a state law requiring distribution utilities to develop cost-effective energy efficiency before constructing expensive new supply. The project was basically an enhanced version of National Grid’s existing energy-efficiency programs, but added demand response on top of them.

New NWA opportunities

In addition to these examples, new NWA opportunities are cropping up across the country. Some are driven by policy changes; others are currently under consideration by regulators.

In January 2017, National Grid partnered with Sunrun to better understand how DERs could be aggregated and used to offer grid services. That partnership expanded in May, when National Grid provided Sunrun approximately $8 million for a share in revenues that arise from new grid services contracts that will be jointly bid prior to June 2019.

In a recent interview, Sunrun CEO Lynn Jurich acknowledged that it’s still early days for the grid services market — largely because regulators are still writing the rules to have utilities consider customer-sited assets. But the fact that National Grid expanded the partnership “gives you some indication that there’s validation, that near-term opportunities for grid services exist,” she said. The two companies have already bid on several grid services contracts, and are expecting to find out if they’ve won in the coming months.

Then there’s New Hampshire, where Liberty Utilities recently asked state regulators to approve a pilot project for 1,000 utility-owned Tesla Powerwalls. Similar to the Green Mountain Power model, Liberty would provide the batteries to customers for a one-time $1,000 fee or a monthly $10 fee. Approximately 300 of the batteries would be installed in homes along a circuit where the utility wants to test the viability of a non-wires alternative to avoid a distribution system infrastructure upgrade.

Interestingly, this is a case where the utility took the initiative to pursue a grid edge solution, and DER provider Sunrun is the party pushing back on the project. They aren’t taking issue with the concept so much as with Liberty’s decision to deploy Tesla products, claiming the pilot basically blocks out competition.

Progress on new grid edge solutions isn’t always linear. In May, New Hampshire regulators pulled back on a plan to develop distributed-generation-only pilot projects designed to identify viable NWAs. A wide range of stakeholders argued that without the inclusion of other distributed energy resources — like energy storage, efficiency and demand response — the study would be unlikely to provide meaningful information.

Regulators agreed, and immediately suspended the implementation of any DG-only NWA pilot programs. Then they launched a study that directs working group members "to evaluate alternative study designs and methodologies to address the potential locational value of DG on the utility distribution system.”

Massachusetts is also getting in on the action. Just this week the Massachusetts House Committee on Ways and Means advanced a bill (HB 4739) that would require utilities to file annual resiliency reports. The reports would include heat maps that show peak energy usage times, congested areas of the distribution grid, and areas vulnerable to outages.

Utilities would have the ability to issue NWA solicitations to meet resiliency needs, including alternatives to transmission and distribution upgrades. Developers would be able to use the heat maps to identify the best locations to propose NWA projects.

Last month, Dayton Power and Light in Ohio reached an agreement with environmental organizations and other stakeholders with respect to its latest rate case. The agreement addresses rates and building out EV charging infrastructure. It also includes a process for developing a non-wires alternative approach to distribution system planning. The plan has been presented to the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, which is expected to make a decision later this summer.

In May, New Jersey passed and signed a major piece of clean energy legislation (A 3723) that modifies energy efficiency programs and boosts the state RPS to 50 percent. It also includes a study to assess whether energy storage technologies can benefit New Jersey's ratepayers by providing backup power, offsetting peak load and offering other opportunities to the state. In addition, the study will address “optimum points of entry into the electric distribution system for distributed energy resources.” This kind foundational work is expected to pave the way for NWA deployments.

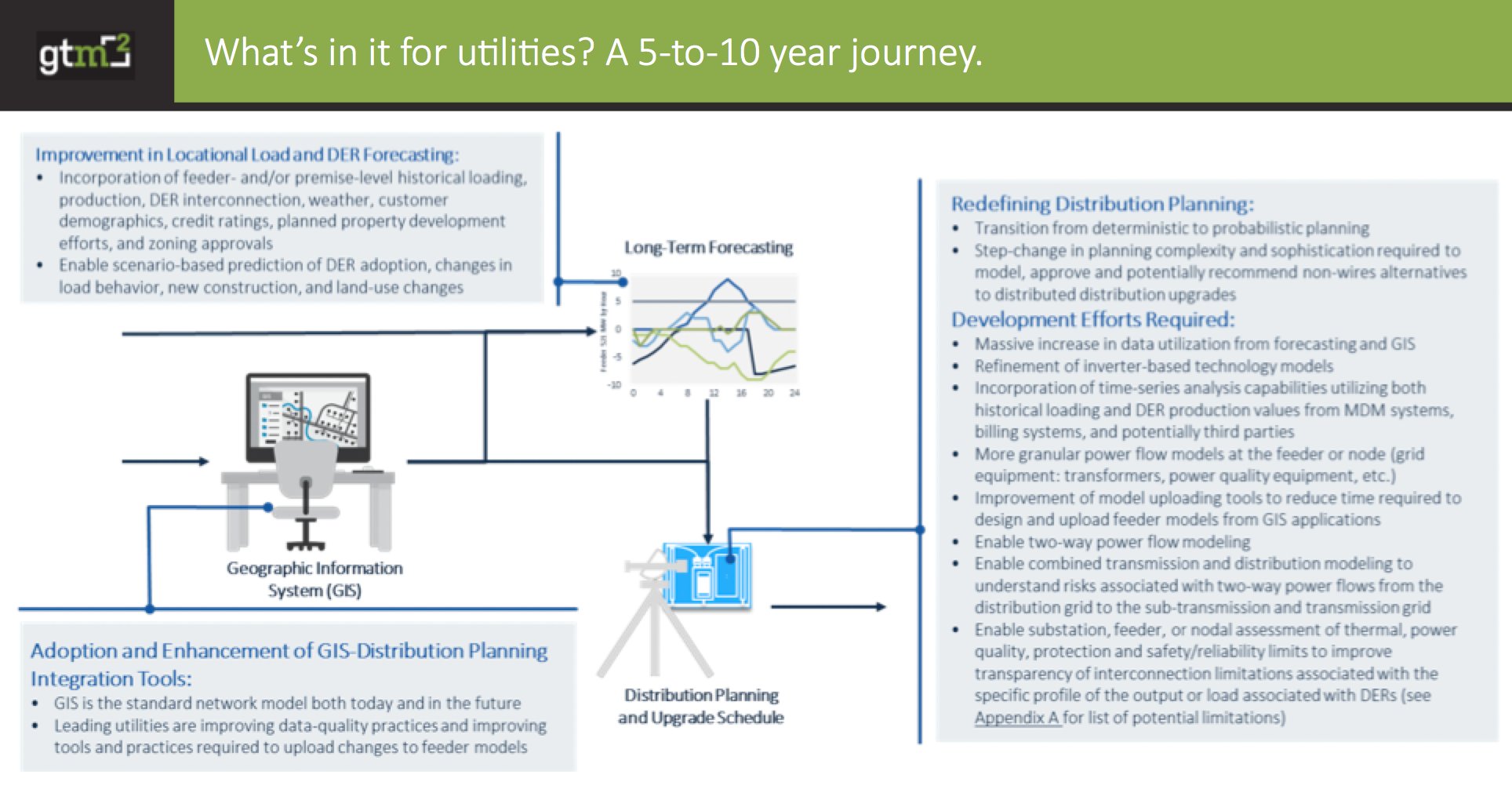

The following slide offers a summary of much of the emphasis of utility and regulator efforts to integrate DERs into future distribution investments. This includes more integration between interconnection services, GIS mapping, distribution planning and long-term forecasting, as well as a broader “redefining of distribution planning.”

Electric vehicles are another technology rapidly transforming the grid edge — and a technology that presents a unique set of risks and opportunities for utilities.

In New York, where policymakers have launched a massive concerted effort to harness the grid edge revolution with the Reforming the Energy Vision initiative, the PSC is currently working through a proceeding that will consider the characteristics of EV charging stations and how they can facilitate EV participation as a distributed energy resource. The docket (18-00561/18-E-0138) launched in April and the PSC held a technical conference July 18 and 19.

EVs have the potential to provide valuable grid services by drawing power from the grid at times when there’s a surplus, and perhaps one day putting power back onto the grid when needed. Most U.S. utilities are not at a point where they’re ready to consider EVs as a grid resource, however.

Most utilities and their regulators are just starting to figure out what role the utility should play in EV infrastructure deployment and how the utility should prepare for the expected influx of EVs on the grid system — let alone use them as grid resources.

According to a recent report from the Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA), many utilities risk being overrun by new peak demand unless they move quickly to adjust their system, rates and demand management programs.

“Our research shows that the situation right now is similar to what we saw with the growth of distributed solar,” Erika Myers, SEPA’s director of research and the report’s lead author, told GTM earlier this year. “If the predictions are correct, many utilities will be caught unprepared, with few ready to take full advantage of this demand by leveraging EVs as a grid asset.”

Utilities are starting to wise up, though. In Pennsylvania, Duquesne Light has proposed an EV ChargeUp Pilot designed to evaluate the grid impacts of EVs and inform distribution-system planning. “This broad initiative includes an evaluation of EV-charging infrastructure, customer rebates, bill credits for customers who register their EVs with Duquesne, and an EV education and outreach component,” according to EQ Research.

Some further-out ideas

In thinking about the intersection of policy and the future of the grid edge, I’ll leave you with three more innovative concepts.

One is Arizona utility commissioner Andy Tobin’s proposal this week to launch a blockchain-specific proceeding. It’s still early days for blockchain deployments in the electricity sector, but it could be transformative — at least according to a group of New York utilities. So it makes sense that utilities and their regulators would want to get ahead of the game. If it moves forward, the Arizona Corporation Commission may become the first state public utility commission in the country to open a docket that is dedicated to understanding blockchain technology in the energy sector.

Another policy-related development to watch is the rise of community-choice aggregators, or CCAs. These local government-run entities often make the case that they’re better positioned to deploy DERs than traditional utilities because they’re inherently more locally focused. Also, a CCA — which is usually established at the city or county level — is roughly the right scale to aggregate and manage a meaningful variety of DERs to provide grid services.

The final development I’ll highlight is legislation introduced in Washington, D.C. that would create a Distributed Energy Resources Authority.The bill would establish an independent authority that has a separate legal existence within the D.C. government. According to Advanced Energy Economy’s PowerSuite, the agency's duties would include the following: “identify policies that may reduce monthly utility bills for consumers; increase the efficiency and reliability of the distribution system, through an independent stakeholder driven planning process; improve distribution system planning for underserved communities; and grow the local energy economy by deploying competitively procured non-wires alternatives solutions to meet the energy needs of the District.”

This novel policy idea could be a game-changer for the deployment of grid edge technologies. However, it hasn’t seen any movement in the D.C. legislature since the spring.