Back in May, we covered California’s integrated resource plan, the state’s effort to maintain a reliable grid as it expands its share of renewable energy over the coming decade. But as we noted at the time, the California Public Utilities Commission has been pushing for its IRP to address some shorter-term grid reliability issues as well — namely, the possibility that closing down natural-gas-fired power plants over the next few years could leave the grid without the resources it needs to meet its peak demands.

Late last month, the CPUC issued a ruling (PDF) that officially opens a “procurement track” for its IRP proceeding that proposes several options to address that need. One option is likely to be welcomed by the state’s clean energy developers and environmental advocates — but two more are likely to draw significant opposition.

The first — and preferred — option is a new, 2,000-megawatt procurement of “peak capacity” resources for California by mid-2021 by the state’s load-serving entities, or LSEs — a group that includes investor-owned utilities Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric, as well as the community-choice aggregators (CCAs) that are taking up an increasing share of the state’s utility customer base. A procurement of this size could be a welcome development for solar industry groups that have pushed for new rules to boost the state’s utility-scale renewable energy market — if it allows for solar-plus-storage and other carbon-free resources.

But the ruling also proposes several alternative options likely to draw fire from clean energy advocates. One is to keep a number of once-through-cooling natural-gas plants on California's coast open past their scheduled closing date of 2021 — a big problem for those pushing for California to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible, as well as for the coastal communities that host these polluting power plants. Another is to order Southern California Edison to solicit 500 megawatts of capacity from “existing resources that are without a contract past 2021,” most likely a natural-gas-fired power plant.

Before these options can be fully considered, however, the CPUC is asking for “comments on options for potential solutions, if parties agree that reliability challenges are possible or likely.” That’s an important point, because there’s significant uncertainty and disagreement among parties on whether natural-gas retirements, combined with the continued growth of solar resources, are actually leading to near-term reliability problems.

And as we’ve noted, there’s a brewing power struggle between the CPUC and CCAs over the IRP, centered on the fact that CCAs are taking up an ever-increasing share of the state’s utility customer base, and thus, an increasing responsibility for procuring the resources needed to keep the grid stable. CalCCA, the group representing CCAs in the state, has already asked for, and received, an extension to the July 15 deadline for comments on the procurement track, as well as to provide the data behind its analysis.

Defining the terms of a potential reliability challenge

Determining whether or not California is facing a near-term reliability problem requires assessing the ability of both in-state generation resources and out-of-state energy imports to supply the state’s demand for electricity. It also requires complex calculations to determine how this mix of resources fits into a grid that’s been altered significantly by the growth of solar power as a major resource, which is driving the state’s problematic “duck curve” supply-demand imbalance.

This issue has come to a head in the past year or so, as grid operator CAISO and the CPUC have been reworking the state’s rules for resource adequacy, or RA — the capacity needed to keep the grid running when demand threatens to outstrip supply. This RA capacity was traditionally needed during hot summer afternoons, when air conditioning electricity usage hits its peak. But with solar’s growth, these peaks are increasingly shifting into the evening hours, as solar power fades away and people come home from work and turn on household HVAC, appliances and consumer electronics.

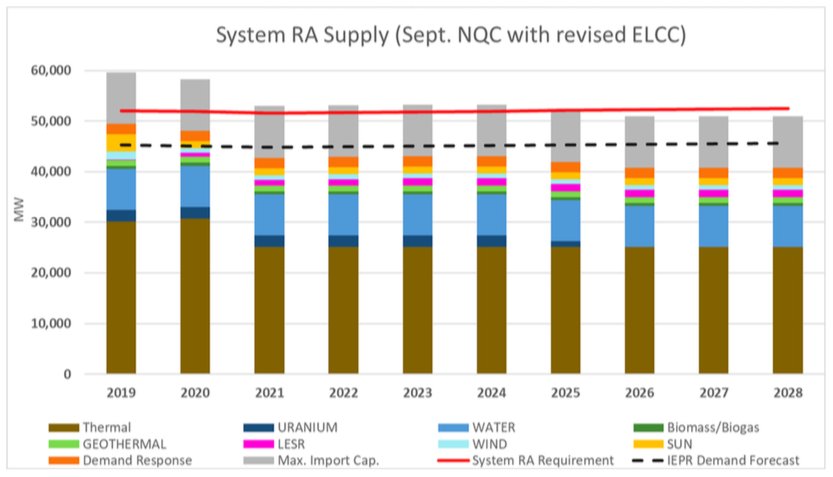

To determine a solar farm’s contribution to meeting these peak needs, the CPUC uses a calculation called effective load carrying capacity. In simple terms, ELCC seeks to determine what share of a solar farm’s total generation capacity will be pumping out electricity at the times when the state’s grid needs it the most. Under the CPUC’s proposed decision on RA, these ELCC factors are set to be reduced significantly during the months of August and September for both solar and wind power resources.

Specifically, for August, solar PV and solar thermal’s ELCC will fall from 41 percent to 29 percent and wind power’s ELCC will fall from 26.5 percent to 21 percent, and for September, solar values will fall from 33.4 percent to 14 percent and wind values will fall from 26.5 percent to 15 percent. In fact, the impact of California’s growing solar resources is projected to shift the state’s overall peak from August to September, when days are shorter and solar resource doesn’t provide as much benefit to the grid, according to the California Energy Commission's most recent Integrated Energy Policy Report.

This near-halving of solar’s value for meeting an LSE’s RA requirement for these two months could significantly “impact the overall supply available to LSEs to count toward their resource adequacy requirements,” the CPUC ruling notes. Even the 1,900 megawatts of solar and 300 megawatts of wind set to come online from now until 2021 will only supply about 300 megawatts of RA under these new factors, it noted.

It’s likely that CCAs will experience the greatest burden from these changes, given that they’ve focused almost exclusively on procuring renewable energy resources to serve their needs, and simultaneously struggled to procure their RA requirements under short-term contracts due to supply constraints.

The CPUC’s procurement track ruling also addresses the issue of out-of-state imported electricity for resource adequacy, using a measurement from CAISO called maximum import capability CAISO uses its recent data for actual electricity imports into the state, along with future estimates, to determine how much it can expect to be able to rely on out-of-state resources in years to come — today, largely Northwest hydropower through the Pacific DC Intertie, along with the potential for a growing share of renewable energy from Arizona, Nevada and states farther east.

California’s reliance on imports for RA is growing, from about 3,600 megawatts or 7 percent of system needs in 2017, to about 4,000 megawatts or 8 percent of system needs last year, the CPUC ruling states.

By 2021, this reliance on imports could grow to 8,800 megawatts of maximum import capability to meet its needs, absent other actions, according to this CPUC graphic of its RA supply in September, based on net qualifying capacity with the proposed revisions to ELCC in place.

“Given historical data on imported resource adequacy used to meet system peak requirements, the proposed adoption of the revised ELCC factors, and the [Integrated Energy Policy Report] peak load forecast shifting from an August peak to a September peak, we are growing increasingly concerned with the ability of the bilateral markets to transact and meet 2021 resource adequacy requirements, given such limited in-state supply,” the CPUC’s procurement track ruling concludes. “There is also the possibility that additional units may mothball and/or retire, exacerbating the tightness of in-state supply.”

The pros and cons of CPUC’s proposed solutions

Of the potential solutions identified by the CPUC’s ruling, the proposal for a 2,000-megawatt procurement of “new peak capacity” to come online by 2021 has gotten the most support from California’s energy industry stakeholders.

“I think this is potentially a pretty big deal,” Sean Gallagher, vice president of state affairs for the Solar Energy Industries Association, noted in an interview last week. “We’ve been arguing that the PUC should order some renewable procurement for about the past two years.”

That argument included a clean energy bill introduced, but not passed into law, by the state legislature last year that would have called for 2,500 megawatts of wind and solar procurement over the next four years. Given the potential boost that a 2,000-megawatt procurement could bring to California solar development, “you’re likely to see our comments more broadly supportive of additional procurement,” Gallagher said.

There’s a catch in the procurement track’s procurement proposal, however — it calls not for renewables in general, but for “new peak capacity” to meet its specific RA needs.

“I think that it would be useful to get a clearer understanding from the PUC about what they mean by peak capacity,” Gallagher said, something likely to be taken up as the procurement track moves through comments and workshops in the coming months.

But in terms of what types of resources are expected to meet that definition, “it’s likely that most of the procurement that will come from this will primarily be renewable procurement,” and more specifically, “primarily solar-plus-storage.” As evidence, Gallagher pointed to some of the massive solar-storage projects being announced in Arizona, Nevada and, most recently, in California by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which have been designed specifically to store and shift solar production from its midday peaks to later hours when the energy is needed.

The Natural Resources Defense Council also generally “supports the concept of a Procurement Track to actualize the clean energy plans developed through the IRP proceeding,” Mohit Chhabra, senior scientist with the NRDC’s climate and clean energy program, wrote in an email this week.

But it does not support the ruling’s proposals to extend the lives of natural gas plants in California, unless it’s done as a “last resort.” Instead, “first, the Commission should try to solve any potential reliability issues through (1) better utilization of available Northwest hydropower, (2) demand response and energy efficiency, and (3) new solar-plus-storage contracts such as the recent LADWP contract with 8Minutenergy,” he wrote.

Chhabra also highlighted the possibility that the CPUC’s calculation of how much of the state’s RA needs can be met by energy imports may be too low, since it “relies on an assumption that past years’ imports are an indicator of future import potential for resource adequacy. Instead of making this simplistic assumption, the Commission should determine the total import potential available for resource adequacy.”

This point brings up a broader issue that CalCCA has raised with the CPUC’s IRP procurement track ruling: the fact that it didn’t include the data behind its analysis. CalCCA’s filing with the CPUC (PDF) notes that “the Ruling only summarizes the analysis and provides limited comments on assumptions,” and asks that the CPUC amend the ruling by adding the data sources, inputs, assumptions and calculation methodologies that led to its conclusions.

UPDATE: In an email sent to CalCCA in advance of a formal ruling next week, a CPUC adminstrative law judge denied the group's motion seeking more data. The email noted that the ruling "contains all of the information necessary for parties to be responsive," and that the methodology used "was simple math, adding together net qualifying capacity information that is already cited and described in the Ruling."