The residential solar industry has a customer acquisition problem. The cost is too damn high.

It's having industry-changing impacts. Smaller installers are steadily gobbling up market share, while bigger installers re-evaluate their sales strategies.

The latest victim in this paradigm shift is Direct Energy, the largest energy retailer in the U.S. The company finally abandoned its residential solar unit this month, in large part because it was spending so much money on new solar customers. Direct Energy Solar's market share slipped quarter after quarter, dwindling from 1.6 percent of the residential sector in the third quarter of 2013 to 0.6 percent in the first quarter of 2017, according to GTM Research's tracking.

Direct Energy jumped into the residential solar business in 2014 after buying Astrum Solar, the eighth-biggest installer in the U.S., for $54 million.

At that time, Astrum's president hailed Direct Energy's "deep relationships with over 6 million residential customers" and said it "will be a winning combination in the growing U.S. residential solar market."

In fact, just the opposite happened. Astrum was integrated into a sprawling company that didn't know much about selling solar. The expected "synergies" didn't materialize.

Direct Energy Solar's customer acquisition costs were far above the industry average (which, at one-quarter the total cost of a system, are pretty high in the first place). Its heavy focus on Massachusetts and failed attempt to expand into California -- two saturated markets where new customers are harder to come by -- caused costs to balloon.

As it turned out, being a smaller installer with lower overhead costs and a strong referral network was more valuable than having 6 million retail customers.

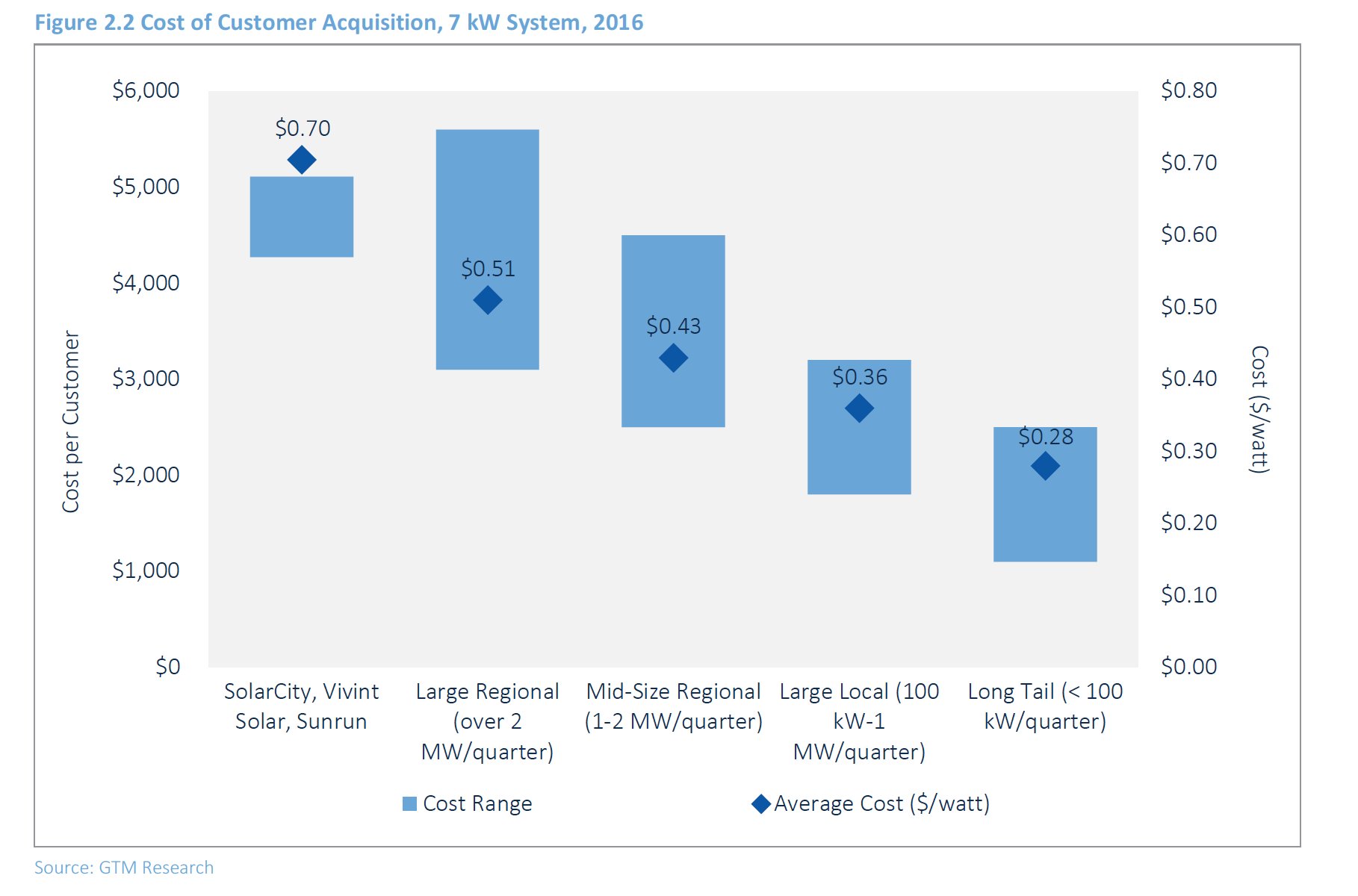

GTM Solar Analyst Allison Mond illustrates this industrywide phenomenon in her latest report on customer acquisition. The top national and regional installers are getting crushed by smaller companies.

Direct Energy's departure from residential is a pretty big deal. It follows NRG's exit from the home solar business in February, after a slew of acquisitions added "layers of management that weren't needed" and forced costs upward.

As NRG Home Solar faltered, its market share followed a similar path to that of Direct Energy. According to GTM Research, NRG's installation volumes fell from 1.9 percent of the total residential market in the first quarter of 2016 to 0.7 percent in the third quarter -- dropping from 11.6 megawatts to 4 megawatts over that period.

So, two of the top retailers in the country showed they were unable to make rooftop solar work.

Three years ago, during the height of the acquisition frenzy, both of these companies talked a big game about becoming national solar brands. They assumed that simply marketing to their network of retail customers would be enough to build a healthy business.

They found out that the hand-to-hand combat of residential solar -- which, along with marketing and advertising, includes referrals, buying leads, bidding platforms, channel partners, door-to-door sales and conversations around the kitchen table -- created a much more complicated sales environment. Add in a bloated sales and management cost structures, and it becomes very hard to compete with more nimble local companies.

There are two things going on here -- one trend that's specific to residential solar, and another with broader implications for large power providers with distributed energy ambitions.

The first is the general rise of "the long tail" in residential solar. We've covered that extensively. Bigger often doesn't mean better.

The second is a potential readjustment of the all-in-one approach to distributed energy services that utilities, competitive power suppliers and other vendors are taking. Recent activity suggests that the ground is shifting a bit.

NRG: After a breathtaking series of company and pipeline acquisitions in an effort to "transform itself from brown to green," NRG is looking to sell off its entire renewables business and become a traditional independent power producer. Investors want to slim the company down and flip projects for quick cash.

Edison Energy: After buying up a group of energy service providers and Altenex, a company that procures large renewable energy deals, Edison International's "new energy future" business is shaking up its executive team and reviewing its approach to the market. The company is losing millions of dollars.

GE's Current: GE paved the way with the "kitchen sink" approach to energy management by bundling smart lighting, solar, EV charging and software/analytics into a package for C&I customers. Late last year, Current initiated a reorganization in order to segment different parts of the business that didn't overlap.

The problems facing each of these companies are unique. However, there is a common theme: Acquiring a bunch of companies all at once and layering in a ton of different energy services doesn't necessarily make for a winning strategy. Sure, these segments are starting to converge, but there are unique challenges facing each of them.

Companies like Direct Energy and NRG realized how complicated and expensive the rooftop solar business can be, even with a large built-in retail customer base. There may be a similar realization coming for others in the C&I space. Like rooftop solar, selling distributed energy services is still hand-to-hand combat -- and no one has yet proven that the all-in-one distributed energy model can work.

The activity underway in this space is dizzying. Utilities across the world are using their unregulated arms to acquire solar, storage, microgrid and energy management firms. (Jeff St. John recently rounded up acquisition activity from Duke, NextEra, Edison International, Enel, Engie and others in a piece from GTM's Grid Edge World Forum.)

But if the tumult in residential solar teaches us something, it's that success through acquisition is very hard in this space.

Utility holding companies may offer up cheaper capital and a sizable customer base, but they also bring bureaucracy and a lack of sector-specific knowledge. Selling rooftop solar or distributed batteries on a project-by-project basis is completely different from selling electrons from the grid to captive customers.

In 2014, two of the biggest energy retailers, Direct Energy and NRG, hyped up their push into residential solar. They expanded too quickly and were soon bogged down by the vagaries of the sector.

Today, we're hearing a lot of the same messaging from power providers buying up distributed energy vendors. Expect similar results.