Unlike fellow grid operators at the California ISO, Electric Reliability Council of Texas and PJM in the mid-Atlantic, the New York Independent System Operator doesn’t have any batteries in its system -- at least, not yet.

As of today, its energy storage participant list is limited to two big, 1,160-megawatt pumped hydro stations near Niagara Falls, and the 20-megawatt Beacon Power flywheel project, spinning away in the grid operator’s frequency regulation market. But with a statewide energy storage mandate now officially a New York policy, NYISO is under the gun to create a model that will admit large-scale batteries into its operations.

New York’s Reforming the Energy Vision (REV) initiative has added distributed energy resources (DERs) and renewable integration to NYISO’s framework. And under one of the last orders issued by the Obama-era Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) last year, NYISO and other grid operators are under pressure to remove the barriers preventing energy storage and DERs from playing in their markets, and quickly -- although in grid operator parlance, quickly can still mean a few years.

On Monday, NYISO released its State of Storage report, a multi-phase, multi-year approach to meeting these pressing obligations to open its markets to energy storage. It’s a high-level review of an exceedingly complicated process, one that’s still just starting to take on the longer-range challenges of managing New York’s aggressive clean energy and distributed energy goals.

But there’s still a lot of new information to delve into, including guidance on how much new solar and wind power New York would need to see before it taps out its existing supply of frequency regulation and ancillary services. There’s also the concept of a future “energy storage resource offer curve” that would allow batteries to buy power at low prices and sell it at high prices in 15-minute intervals, to help match batteries' operating flexibility with real-time market needs.

Today’s market structures are a long way from realizing this more flexible use of energy storage. Like the rest of the country’s grid operators, NYISO has only started to create the models that take advantage of energy storage’s unique characteristics, while setting a fair playing field against other resources in the mix.

Still, as Mike DeSoccio, NYISO’s senior manager of market design, said at a Monday press conference: “We are aware of storage resources today that are looking to participate, and we expect there will be more of them as they become more cost-effective and as policies evolve.”

A new model for a unique resource

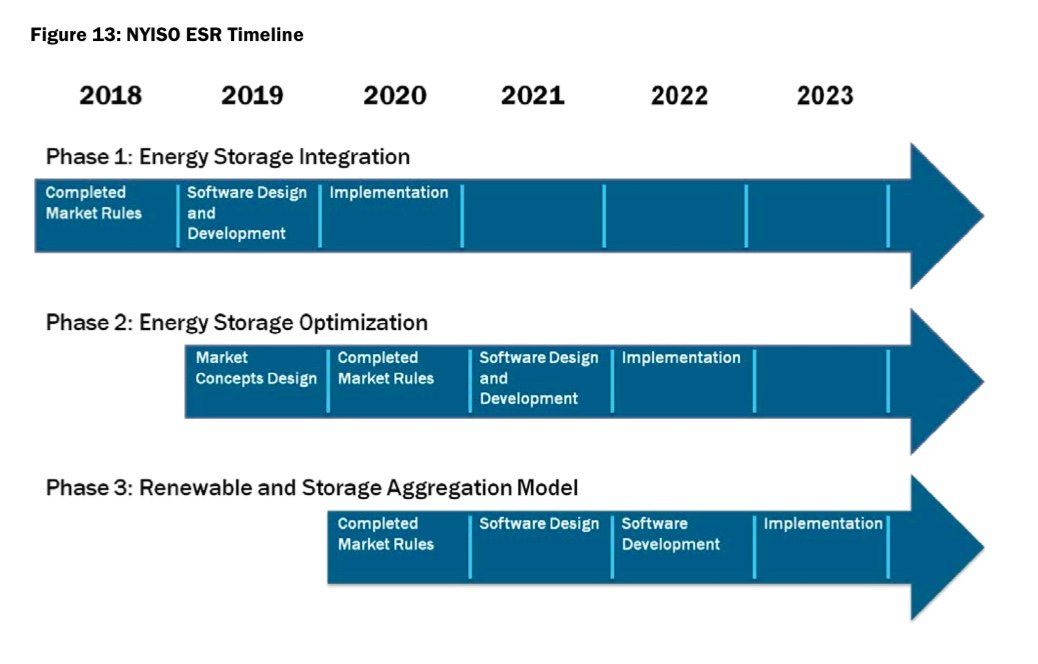

NYISO’s first phase, dubbed the “Energy Storage Integration Phase,” will run through 2020, with the goal of identifying “parameters important to include in an energy storage resource offer.” The chief challenge here is to create a new model for a resource that’s unlike any other now in use on the grid.

Energy storage offers both advantages and disadvantages compared to generation or demand-side resources. On the plus side, it is a fast-responding resource that can both inject and absorb real electricity. On the minus side, it doesn’t actually generate its own electricity, and has limitations to how long, and how often, it can serve at its nameplate capacity.

These characteristics don’t necessarily fit well into NYISO’s existing structures. These include day-ahead and real-time markets for energy, regulation services, and operating reserves, as well as a capacity market that recently made the switch from year-round to summer and winter auctions.

Today, energy storage resources can take part in those markets under NYISO’s limited energy storage resource (LESR) and energy limited resource (ELR) programs, as well as existing demand response programs, primarily its demand-side ancillary services program (DSASP) and its installed capacity special case resource (SCR) program.

In some ways, NYISO has been a trendsetter in these fields. For example, it was the first ISO to allow storage to serve in frequency regulation services in 2009, although that market opportunity was quickly supplanted by PJM’s frequency regulation market, which became the country’s biggest energy storage opportunity before crashing last year and this year.

But NYISO”s “current models, like ELRs, LESRs, DSASP, and SCRs, do not fully capture the services that storage can offer to the market,” NYISO’s white paper notes. Largely that’s because these models were built for generators that add energy to the grid, or demand response that subtracts load, not energy storage, which can do both, albeit within significant operating constraints.

One of the problems with these programs is that they require minimum amounts of power for multi-hour commitments that may be hard for most battery technologies to serve. LESRs and ELRs, for example, must provide at least 1 megawatt for at least 4 consecutive hours each day, which works for pumped hydro or flow batteries, but pushes the envelope for today’s lithium-ion batteries.

NYISO intends to remove some of these barriers in its new market participation models, by creating structures for resources as small as 100 kilowatts in size, either as part of standalone energy storage resources or as part of a collection of DERs. But one of its most interesting changes involves a new structure for giving storage the flexibility to charge and discharge as quickly as prices change on the grid.

“Currently there is no market model in New York that would allow ESRs to change from producers to consumers intra-hour,” the paper notes. That’s a problem for resources that have to buy electricity before they can sell it back, and “obtain the greatest value from buying energy in low-cost intervals and reselling it during high-priced intervals.”

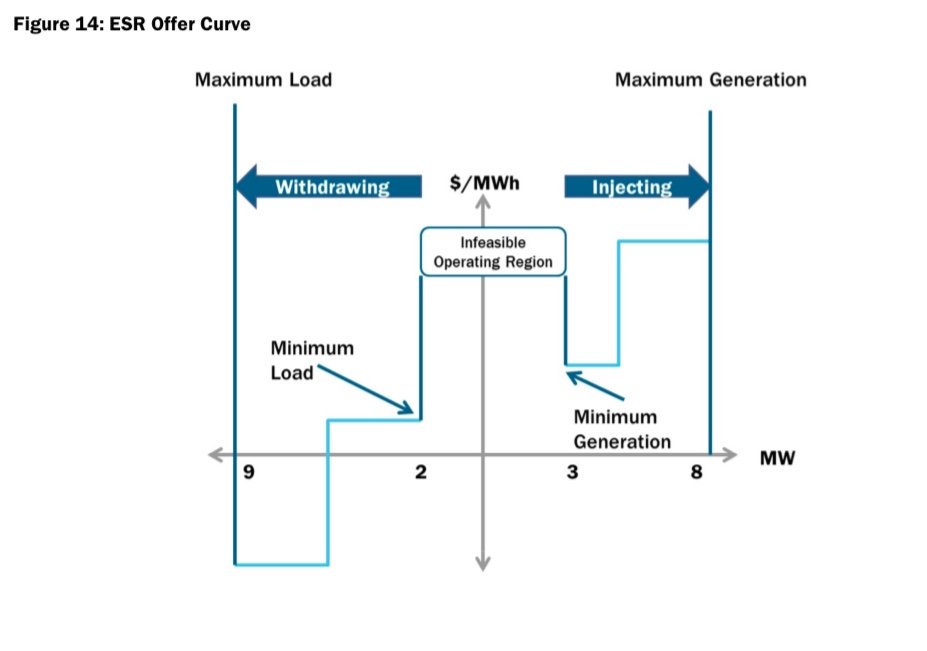

Forcing an energy storage resource to pick whether it’s going to act like a generator or a load from hour to hour would be a misuse of the flexibility inherent in the technology, the paper noted. To solve that problem, NYISO has come up with its ESR offer curve, described as shown in the following chart.

In this model, the storage system would charge (i.e., act like a load) when local marginal prices fall to or below its bid price for buying energy; and inject energy like a generator when local marginal prices meet or exceed its sell offer. These offers would be settled at increments as tight as every 5 minutes, dubbed nodal increments, and dispatched via NYISO’s existing real-time commitment and real-time dispatch software.

More ISO control, renewable integration and next steps

NYISO’s second phase, or “Energy Storage Optimization Phase,” is set to begin in 2019 and run through 2022. The main difference between it and the first phase is that it will add the option for energy storage resources to start allowing the ISO itself to set charge and discharge parameters for its moment-to-moment operations.

The chief benefit of this step would be to allow the grid operator to manage the daily energy constraints that are otherwise left to the storage operator to predict and add to their bids as cost-adders. “In Phase 2, the NYISO hopes NYISO-determined deployment of the ESRs will not only lower generators’ production costs, but also improve market efficiency,” the grid operator noted.

The third phase, set to start in 2020, will study the pairing of energy storage with intermittent renewables -- the use for which storage is most often cited as the “holy grail,” but one which is still very much in the initial stages of planning.

“Several developers and market participants have expressed interest in aggregating storage resources with renewable energy resources to “firm” the variable resources into a controllable, dispatchable unit,” the white paper noted. The NYISO will consider the necessary model, software and tariff changes needed to allow ESR to both firm renewable energy behind the meter and to offer other ancillary services.”

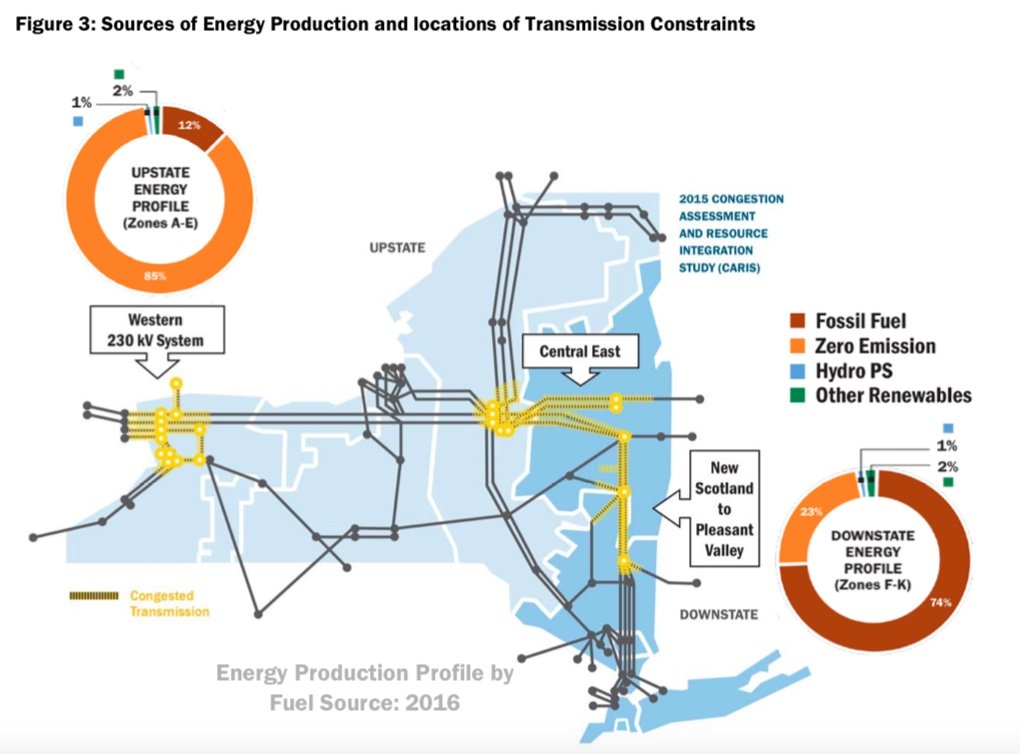

Right now at least, NYISO isn’t anticipating that the state’s growth in wind and solar generation will require a lot more energy storage to help balance grid frequency or manage ramp rates. The white paper projects that existing regulation service requirements will “be sufficient to balance the variability of new wind and solar resources up to the point where solar penetration exceeds 1,500 MW of installed capacity, or installed wind capacity grows to exceed 2,500 MW,” which is well beyond current levels.

But as with other states with aggressive renewable energy and carbon emission reduction goals, New York is moving into uncharted territory in terms of the resources it will need to balance a grid made up increasingly of intermittent resources.

“ESRs, like other fully dispatchable resources, can...respond to economic signals to help manage the variability of intermittent resources,” according to the report. “Absent system constraints like congested transmission, storage could ‘firm’ renewable energy by saving excess production or by supplementing injections during underproduction.”

NYISO is also looking for energy storage that can help it manage its increasingly congested transmission grid, with the preponderance of generation upstate, but most of its load downstate and in New York City. This could be done by storing renewable energy for delivery when the transmission system is less constrained, or by providing downstream storage to serve loads when those constraints are at their peak.

This fundamental imbalance between upstate and downstate is one of the big drivers behind the energy storage mandate passed by the state legislature this summer and signed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo last week. While the mandate still lacks a hard megawatt target, it puts New York in a small club of states that have made energy storage a specific target for policy backing, including California, Oregon and Massachusetts.

At the same time, grid operators like NYISO are duty-bound to remain technology- and vendor-neutral when it comes to setting the rules of its day-ahead and real-time energy, ancillary services and capacity markets.

“What we are trying to do here is to remove barriers to storage to integrate into the marketplace,” said Rana Mukerji, senior vice president of market structures. “The actual penetration levels of technologies will be based on other economic factors -- what’s the price of natural gas, what’s the intermittency in the system that drives price fluctuations, and what are the incentives that storage is getting from the state or public policy initiatives.”

Many of NYISO's longer-range plans for energy storage integration are wrapped up in its plans to integrate distributed energy resources. For example, "it is envisioned that FTM [front-of-meter] storage and DER will function under similar models in the capacity market. Consideration of the capacity market model for FTM or aggregated ESRs will begin in 2018." That's also when NYISO intends to work on how storage included in non-wires alternative projects being built by New York's utilities might play in its wholesale markets at times when they're not being called upon to keep the distribution grid running.

The release of the State of Storage report is just the latest development in a long and complex discussion on how batteries and other storage systems can meet the state's grid reliability needs.