A lot of U.S. utilities are unprepared for the rapid increase in electric vehicles coming onto their grid systems.

According to a recent report from the Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA), many utilities risk being overrun by new peak demand due to a large concentration of EVs, unless they move quickly to update their system, rates and demand management programs.

"Further, many utilities do not want to just serve this new load — they want to take advantage of EVs as a distributed energy resource (DER) with the ability to modulate charge (i.e., managed charging), or even dispatch energy back into the grid (i.e., vehicle-to-grid)," SEPA noted. "Utilities need to understand and leverage distributed energy assets, including EVs, as grid assets to allow for greater penetration of renewable energy — among many other benefits."

In the third and final segment of this series, we look at the benefits of well-designed utility EV policies, the risks of inaction, and some of the policies utilities are already pursuing.

(Click here to read Part 1 and Part 2.)

EVs won't destroy the grid, but will create grid challenges

If utilities don’t respond to EVs at all, they could soon have a problem on their hands. Whether or not they supply the charging infrastructure, utilities have to have enough electric generation available to power the EVs, and a grid system strong enough to handle them.

According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, electricity consumption from EVs could grow from a few terawatt-hours per year in 2017 to around 118 terawatt-hours per year 2030. The sheer increase in electricity demand from e-mobility isn’t expected to be that big of an issue, but managing that increase could be.

A recent report by McKinsey states, “while the uptake in EV sales is unlikely to cause a significant increase in total power demand, it will likely reshape the electricity load curve.” The most pronounced effect will be an increase in evening peak loads, as people plug in their EVs after work. At a system level, this will have a relatively small impact, but at a local level the impact could be significant because the regional spread of EVs will vary, with a concentration in suburban areas.

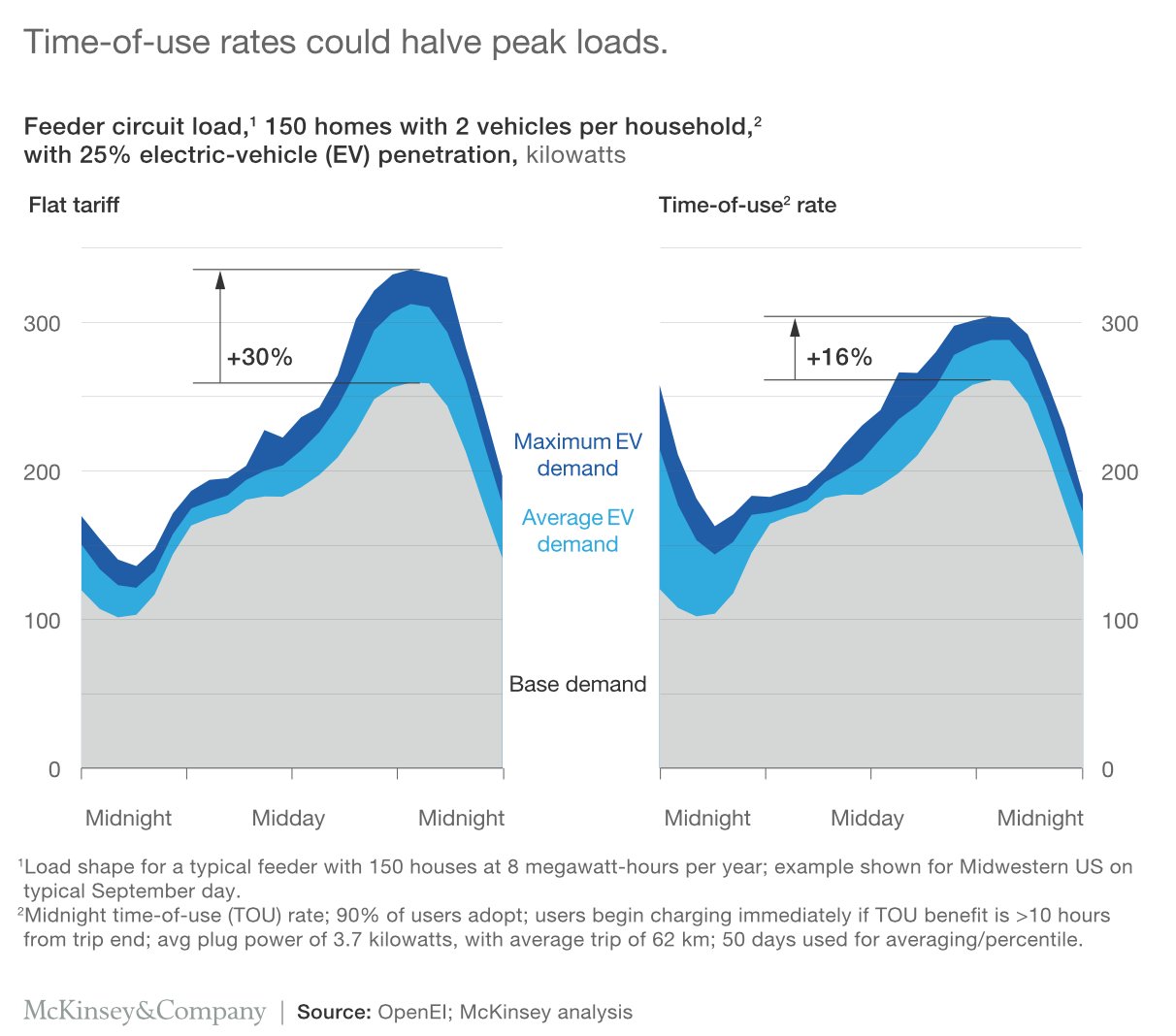

Using Germany as an example, McKinsey found that a typical residential feeder circuit of 150 homes at 25 percent local EV penetration, would see local peak load increase by approximately 30 percent. Beyond peak-load increases, the highly volatile and spiky load profiles of public fast-charging stations will require additional system balancing.

“Unmanaged, substation peak-load increases from EV-charging power demand will eventually push local transformers beyond their capacity, requiring upgrades,” the report states. “Without corrective action, we estimate that the cumulative grid-investment need could exceed several hundred euros per EV.”

Time-of-use electricity tariffs are one solution utilities can implement. TOU rates reflect the higher cost of providing electricity during periods of peak demand, and conversely, the lower cost of service during off-peak periods. This can save EV owners money, and reduce peak demand, which reduces the need for peak-demand related capital expenditures and saves money for everyone.

But these programs have to be monitored, because they could result in “timer peaks,” according to McKinsey, which occur when many people set their EVs to start charging at the same time. If deployed well, however, TOU rates could halve peak loads.

Another option is to co-locate an energy-storage unit with the stressed transformer to charge during times of low demand. The storage unit then discharges at times of peak demand, thus reducing the peak load. Using energy storage to smooth load profiles makes a lot of sense, but it is far from mainstream.

Using smart charging to shift EV loads is also a solution. “Early insights into the charging behavior and the driving and parking patterns of EV owners suggest that for a significant share of the time that EVs remain connected to the grid, they are not actively charging,” the McKinsey report states. “This situation creates the potential to shift the charging load and thereby optimize charging times and speeds from a system perspective, thus making charging smart.”

Vehicle-to-grid systems — which not only shift the power demand from EVs but also make it possible for EVs to feed energy back into the grid — represent another valuable tool. However, it’s still early days for this technology.

Whatever approach a utility decides to take, it will have to go through a policymaking process in collaboration with utility regulators and other stakeholders, as discussed in Part Two. Below, we look at actions utilities are already taking.

The biggest EV policy trends (don't include ratemaking)

Time-sensitive EV charging is starting to take off, but it's still very much early days.

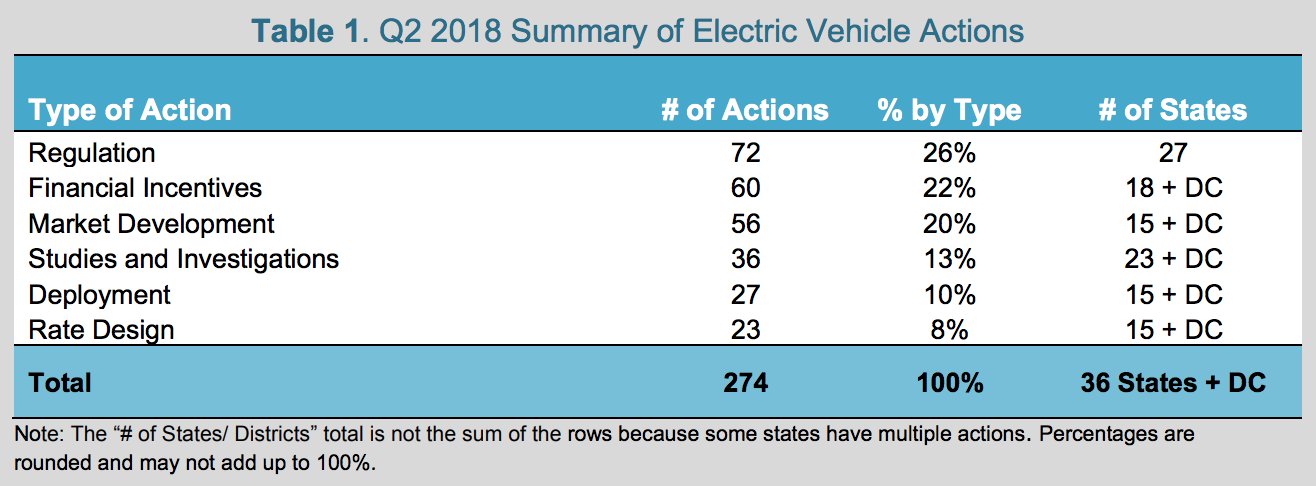

In the second quarter of 2018, 36 states and the District of Columbia took actions related to electric vehicles and charging infrastructure, according to the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center's (NCCETC) Q2 2018 edition of The 50 States of Electric Vehicles report. A total of 274 electric vehicle actions were taken during that period. Seven states — New York, New Jersey, California, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Vermont and Minnesota — accounted for over half of them.

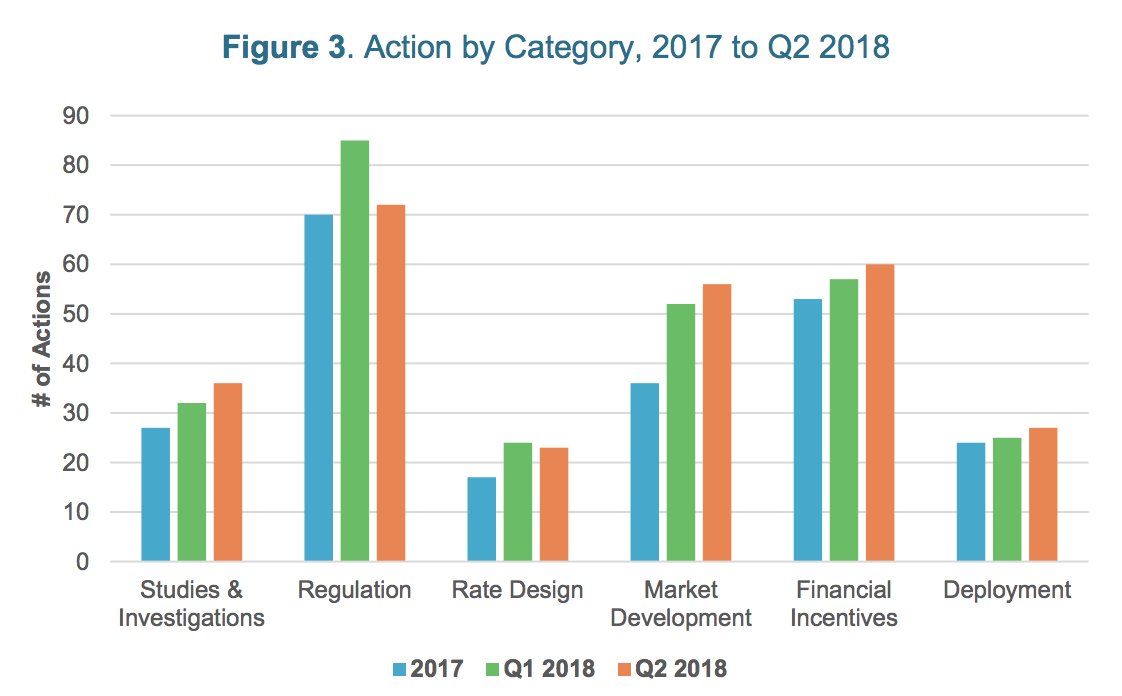

Of the 274 actions last quarter, EV-related rate design changes accounted for just 23 of them. The greatest number of actions taken were labeled as "regulation," which NCCETC defines as "changes to state rules related to electric vehicles, including registration fees, homeowner association limitations, and electricity resale regulations affecting vehicle charging."

Market development, financial incentives, EV studies and charging station deployment have become an increasing priorities for utilities and their regulators over time. Meanwhile, the number of actions related to EV rate design actually dropped last quarter.

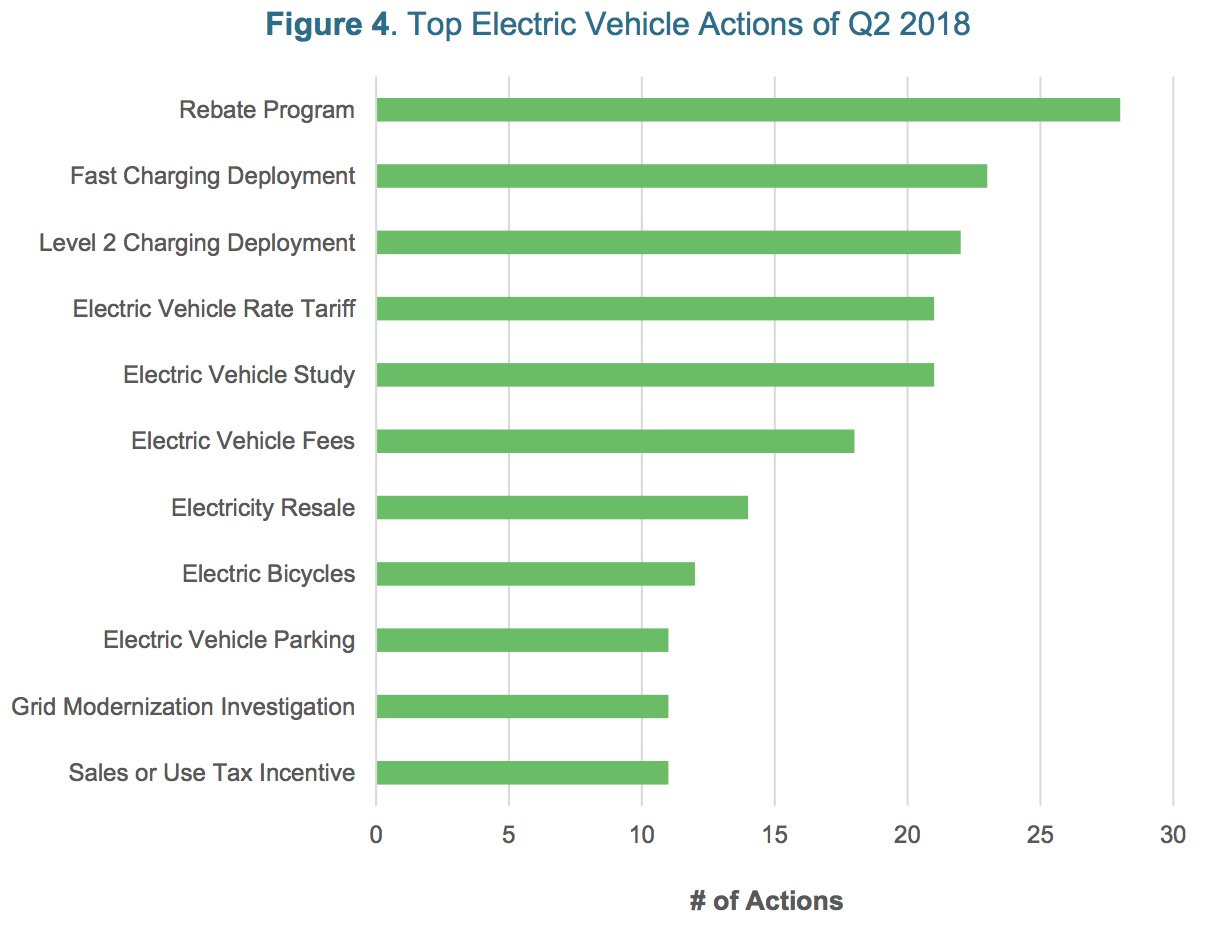

Broken down into more detail, the greatest number of actions in the second quarter of 2018 were related to EV rebate programs, followed by DC fast charging and Level 2 charging station deployment — policy actions addressed in Part One and Part Two of this series.

In this analysis, EV tariffs rank higher on the list of priorities. But the number of electric bicycle actions, for instance, aren't all that far behind, which is somewhat surprising given that electric bikes are likely to have far less impact on the grid than plug-in cars.

The NCCETC report found that three biggest trends in EV activity apparent or emerging in the second quarter of 2018 were: 1) states diverging on the issue of regulatory oversight of electric vehicle charging stations, 2) states and utilities working to expand electric vehicle and charging access to low-income and disadvantaged communities, and 3) electric vehicle activity concentrating in particular states and regions.

The quarter’s five most notable EV actions according to NCCETC are:

- California regulators approving $738 million for electric vehicle infrastructure investments.

- Governor Cuomo announcing up to $250 million for electric vehicle expansion in New York.

- The Public Utilities Commission of Nevada permitting NV Energy to own, operate and rate-base EV charging infrastructure.

- The Vermont State legislature initiating an investigation into electric vehicles and charging.

- Utility regulators in Alabama and New Orleans addressing oversight of electric vehicle charging stations. Regulators in both states determined that electric vehicle charging station owners and operators will not be classified as public utilities, subject to PUC regulation. This issue remains unaddressed in many states, with this issue also under consideration in Q2 2018 in Delaware, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Pennsylvania and Vermont.

Next-level EV regulation

Expanding access to EV charging is one of the first and most important steps in expanding transportation electrification overall, as addressed earlier in this article series. But in order to ensure that EVs are a benefit and not a liability for the grid, utility rates and programs will need to become more sophisticated at the same time.

Several states are already EV regulation to the next level — beyond EV charging infrastructure funding programs to specially designed EV tariffs that leverage plug-in vehicles as resources. Some progressive utilities, like Con Ed, have offered EV time-of-use rates for years, while others, like DTE and CMS in Michigan, are just starting down this path.

Commissioner Dunn in Arizona, for instance, launched a new proceeding into EVs in August that will investigate, among other things, the utilization of rate design to promote charging infrastructure; standardization and interoperability; and future EV opportunities, such as EV rideshare and vehicle-to-home charging. Arizona regulators will host a workshop by November 2018 to begin this investigation.

In New York, utility regulators opened a proceeding in April "to consider the role of electric utilities in providing infrastructure and rate designs to accommodate the needs and electricity demands on electric vehicles and electric vehicle supply equipment," as well as "the characteristics of EV charging stations and how they may facilitate EV participation as a distributed energy resource," according to Advanced Energy Economy's PowerSuite. A working group meeting to discuss rate design principles for EV charging stations in New York is scheduled for September 21.

As noted above, Con Ed already offers New York EV customers rewards for charging at off-peak times. One way in which the new proceeding takes EV ratemaking a step further is by concentrating on appropriate rate structures for DC fast charging and reducing range anxiety. A prominent issue here is that fast-charger operators are often hit with high demand charges when these stations are used, because they create a sudden spike in electricity usage. These painful charges can discourage the build-out of charging equipment, which can discourage potential EV customers. The LBNL EV report referenced in Part 2 addresses the demand charge issue in detail.

In California, meanwhile, BMW is working with Pacific Gas & Electric to optimize EV charging for when wholesale market electricity prices are low and for when there's a surplus of renewable energy, as I recently reported. The pilot was made possible by a California Energy Commission EPIC grant. However, to make this kind of advanced charging application economically sustainable, BMW's Adam Langton said that utility regulators need to step in to help figure out exactly much value this application creates for the utility, so that programs can be rolled out at a much larger scale.

"There's room now to start growing these [types of programs] much, much larger...giving the utilities much more experience with engaging with electric vehicles as a resource," Langton said.

Policymakers, at multiple levels of government, have lots of tools at their disposal when it comes to shaping the EV policy landscape. I've outlined many of those tools and how they're being put to use in this series. Some states, such as California and New York, are on the leading edge of advanced EV regulation, while other states are just starting down this road.

One major takeaway that emerged in reporting this State Bulletin series: Doing nothing is not an option.