ExxonMobil reported its third-quarter earnings Friday at $6.2 billion, a 57 percent increase over the same period last year. According to the oil and gas company, its cash flow from operating activities is the highest it has been since Q3 2014.

But that healthy financial report belies challenges many analysts say are coming for companies that rely on fossil fuels. At Greentech Media, we often cover how oil and gas majors are confronting — or avoiding — a future changed by the energy transition. Exxon is among the U.S. companies somewhat sheltered from pressures to move toward a more sustainable business model. But that protection may not last. A recent report from Goldman Sachs adds another voice to the chorus pushing oil and gas majors toward a strategic transition.

The report argues that becoming “broader, cleaner energy providers” (what Goldman describes as “Big Energy”) can yield greater returns and a new source of value for majors. Though “Big Oil” companies account for just 10 to 15 percent of global power-sector emissions, reorienting those companies could also result in carbon emissions reductions of over 20 percent in that sector. Plus, the bank notes, transitioning is essential to shield majors from a similar plight to that faced by companies now being impacted by the downfall of coal.

“We believe that it is very important for Big Oils to lay out a strategy toward becoming Big Energy…in order to avoid the divestments and de-rating that the coal sector has experienced over the past five years,” reads the report.

Challenges for fossil fuels

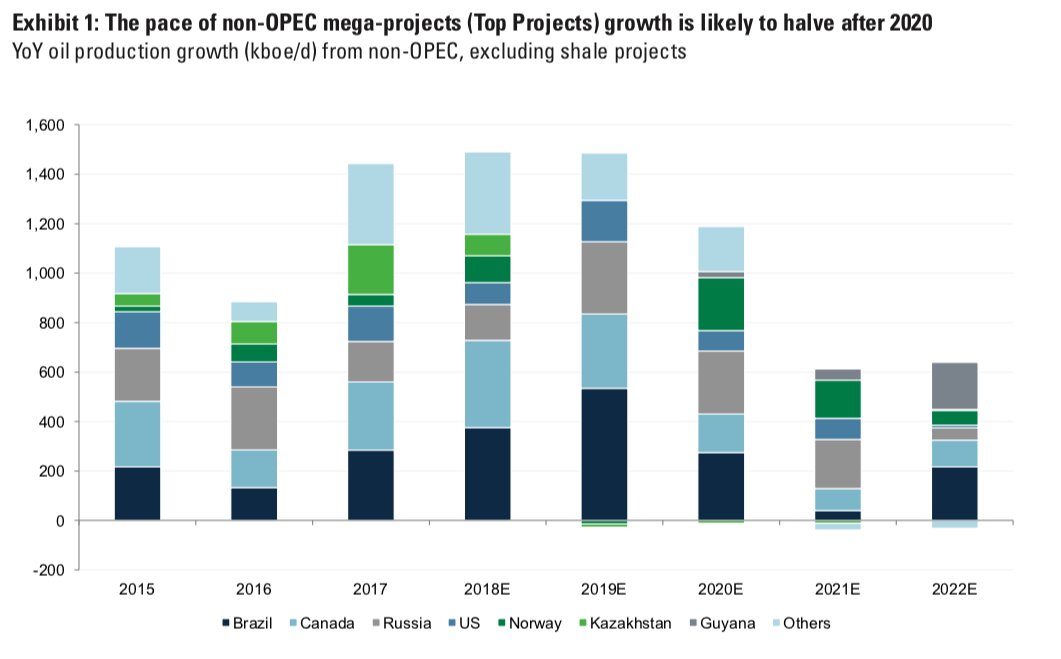

Two trends buttress Goldman’s argument: a coming drop in oil projects from non-Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the high growth potential of renewable energy.

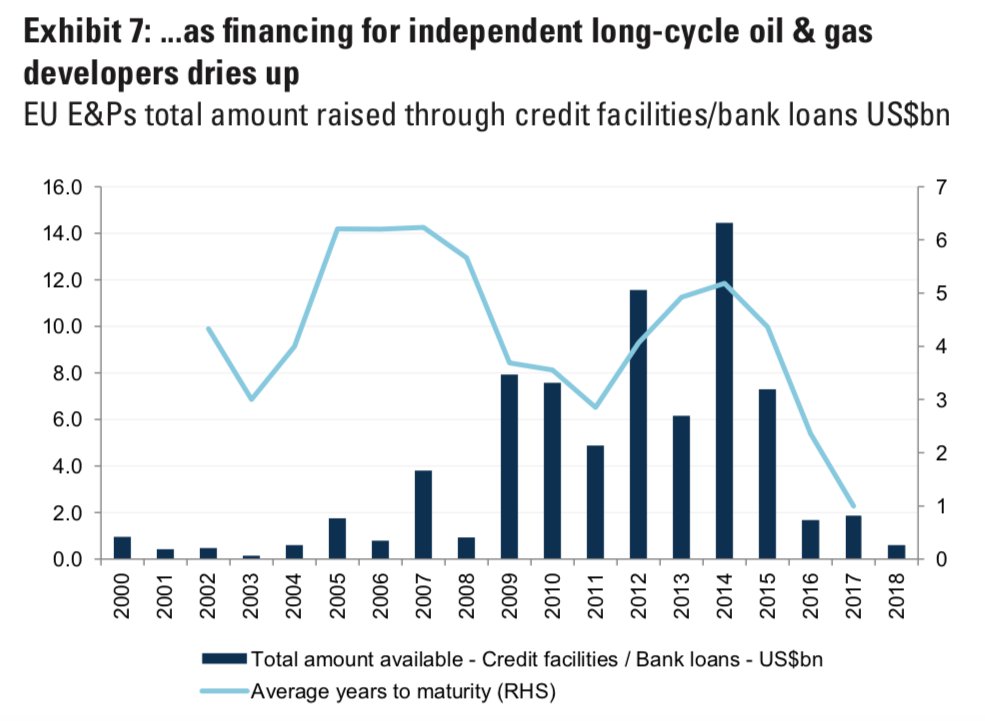

According to Goldman, financing for oil and gas projects is harder to come by than it was 10 years ago, with financial institutions curbing the risk associated with long-lead-time oil and gas projects.

Source: Goldman Sachs

The dwindling availability of finance prompted the majority of companies to stop developing huge projects in 2014. Financing in 2015-2018 was markedly lower than in years past.

Source: Goldman Sachs

The market will feel the effects of those financing changes in 2020, when the number of “mega-projects” in non-OPEC countries declines. Another drop is forecasted to come in 2021. Goldman suggests that will cause delays in financial investment decisions on projects, ultimately bringing a loss of 5.6 million barrels per day of production by 2025.

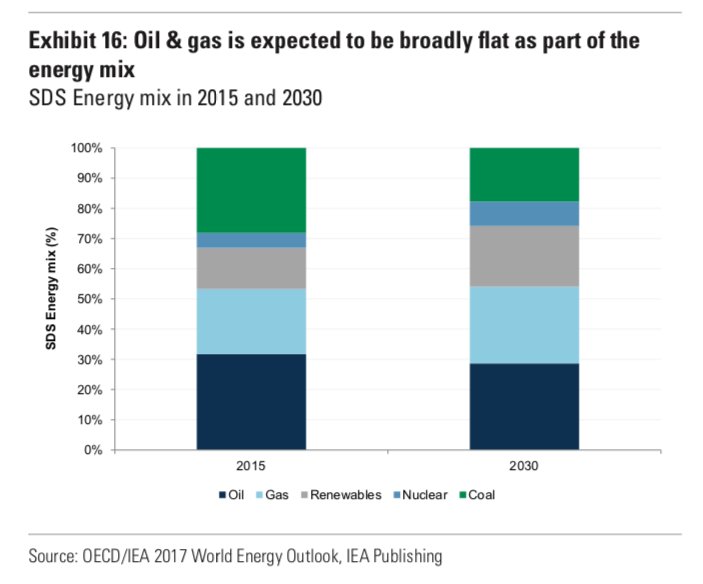

And while oil and gas demand remains steady through 2030 despite those headwinds, renewables demand will also grow by 50 percent.

Goldman suggests majors take advantage of that growth, rather than ignoring it, to avoid the fate of companies now coping with the demise of coal. As the energy transition continues, clean energy will account for a larger and larger portion of the power supply.

In 2017, Goldman notes, the number of institutions divested from coal neared 1,000. Just four years before, divestments hadn’t passed the 200 mark.

Source: Goldman Sachs

The type and size of companies walking away from coal varies. Goldman points to financial institutions such as JPMorgan Chase and HSBC, which said they “will stop providing financing for new coal-fired power plants as part of...efforts to support a transition to a low-carbon economy.”

Financing challenges indicate oil and gas could face a similar future. European banks, which traditionally had been the top choice for large oil and gas projects, decreased their exposure to that industry since 2014. French bank Credit Agricole, for instance, reduced its exposure from 16 percent in 2014 to 5 percent in an effort to “exclude the financing of the least energy efficient and most environmentally hazardous hydrocarbons.”

Transitioning to “Big Energy”

Goldman presents its “Big Energy” reorientation as an alternative that allows majors to avoid the business challenges associated with falling interest in fossil fuels.

Though the bank finds that gas demand will grow by 19 percent through 2030, renewable energy demand grows even more markedly during that time frame: 50 percent.

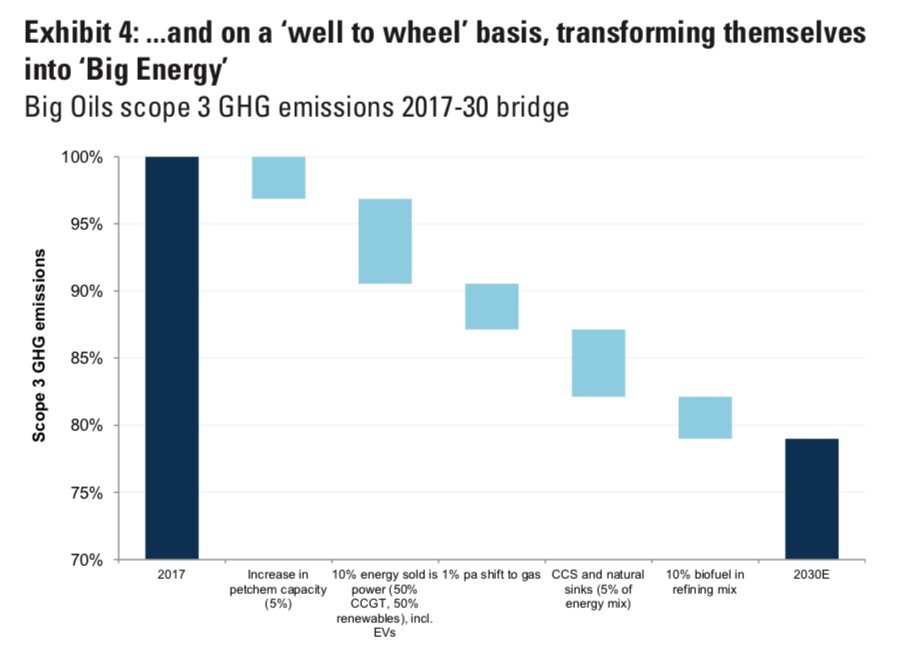

Oil majors could drive a transition toward cleaner energy, and the related decrease in emissions, by converting 10 percent of their energy sold to electricity split between combined-cycle gas turbines and renewables.

Source: Goldman Sachs

“We believe the coming decade will see [Big Oils] integrating vertically in gas and power, leveraging their brand and trading capabilities to acquire gas and power customers,” write the Goldman analysts.

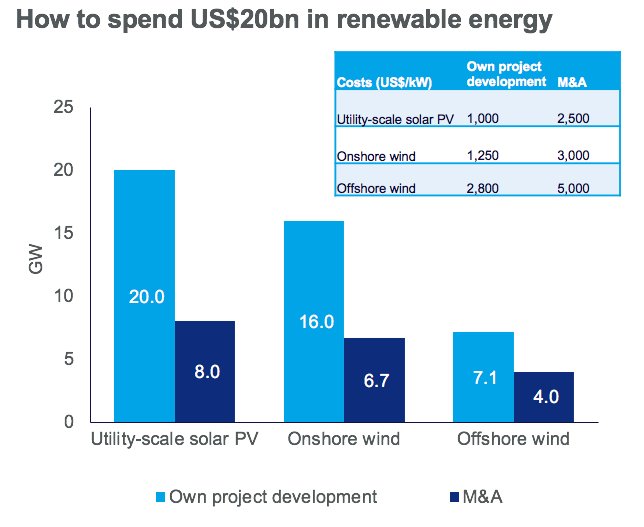

According to Goldman, the investment required for that low carbon transition in the renewables space equates to $9 billion, or just 9 percent of oil and gas majors’ 2019 capital expenditures. Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables calculates that if oil and gas majors want to match their dominance in fossil fuels in clean energy, it would require investment of $20 billion per year.

European majors have already moved toward more renewables investments. Goldman believes that by 2030, those companies will spend 10 percent of their capital expenditures on renewables.

The lower returns that come along with renewables projects could deter majors from those investments. But Goldman argues that the higher returns majors have enjoyed in fossil fuels should offer those companies the funding they need to “re-imagine their business.”

If oil and gas companies invested as much in renewables as they do in oil and gas, it would mean “a massive boost for the market,” according to WoodMac Senior Solar Analyst Tom Heggarty. Even the largest clean energy acquisition to date, Global Infrastructure Partners' purchase of Equis Energy, equates to only a quarter of WoodMac’s forecasted $20 billion, meaning that even smaller investments are a significant boon to solar and wind markets.

Source: Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables

For an oil and gas major to spend the amount WoodMac suggests, it would have to develop 16 gigawatts of onshore wind or up to 20 gigawatts of utility-scale PV. Going the merger and acquisition route, a major would have to buy at most 8 gigawatts of already-developed utility-scale solar.

Where majors can look for major change

The transition will also be easier for some majors than others.

According to Goldman, companies that focus on upstream business — like Equinor and Eni — have less flexibility to cut emissions produced through the consumption of their products, known as “scope 3” emissions.

At the same time, Equinor has framed itself as a leader among majors. It set a carbon dioxide reduction target in 2000 and even changed its name this year to reflect its transition to a “broad energy company.”

Among its peers, the company has the lowest upstream greenhouse gas intensity for operations-related emissions, indicating it’s possible to overcome the challenges associated with its upstream focus.

Goldman forecasts that by 2030, Equinor can reduce its direct and indirect operations-related emissions by 21 percent and emissions from the use of its products by 13 percent. By 2020, the company said it will devote a quarter of its research funds to energy efficiency and new energy solutions.

U.S. majors ExxonMobil and Chevron have followed a different path in the upstream sector. Less governmental pressure plus the exposure to cheap oil has protected those companies and made them more comfortable looking toward the future, according to Valentina Kretzschmar, WoodMac’s director of corporate research. But Goldman also notes that if Exxon drops its involvement with Canadian oil sands, it could reduce greenhouse gas emissions 11 percent from 2017 levels by 2030.

A focus on downstream refining and natural-gas sales, like the businesses of British Petroleum and Shell, allows for more options to cut product-related emissions. Goldman notes that both companies are focusing on expanding their renewable energy businesses, which would cut scope 3 emissions.

Goldman’s report also addresses overarching concerns from majors about transitioning their business. Both Goldman and WoodMac recognize that renewable energy projects mean lower returns than oil and gas. Goldman, though, notes that majors can balance the lower 5 percent returns it projects for renewables projects with higher returns on oil and gas plays as the market gets more competitive.

While Goldman cites future internal rates of return (IRRs) at 16 percent for oil and 17 percent for gas, the “Big Energy” business comes in just behind those markets with a 13 percent IRR.

Goldman also challenges the myth that the lower returns from renewables projects must come with higher investment.

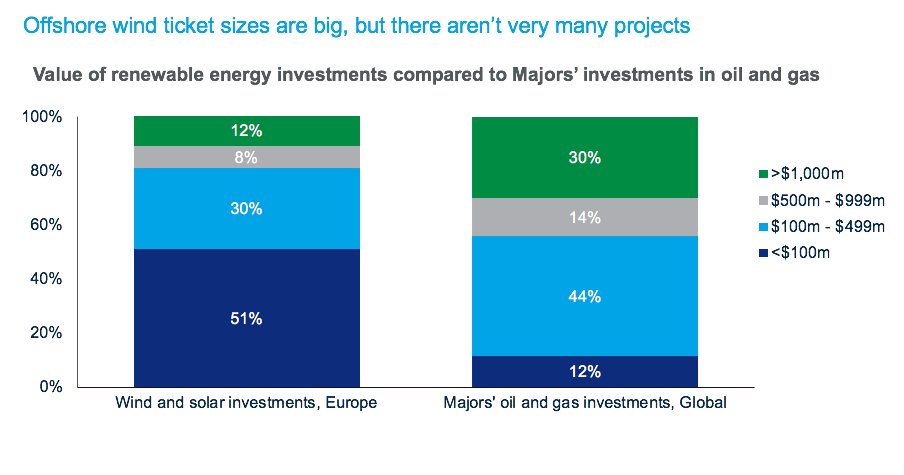

Source: Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables, Prequin

The above chart from WoodMac indicates that oil and gas projects are often significantly more expensive than wind and solar investments in developed markets, such as Europe. The majority of oil and gas investments are between $100 million and $499 million, while European wind and solar investments more often cost less than $100 million.

Majors can also look to mergers and acquisitions to guard against the energy transition. Many have already bought up or invested in clean energy technology companies, hedging their business for when the transition accelerates. Total, for instance, acquired a majority stake in SunPower, Shell acquired a stake in solar developer Silicon Ranch, and BP acquired a stake in solar developer Lightsource.

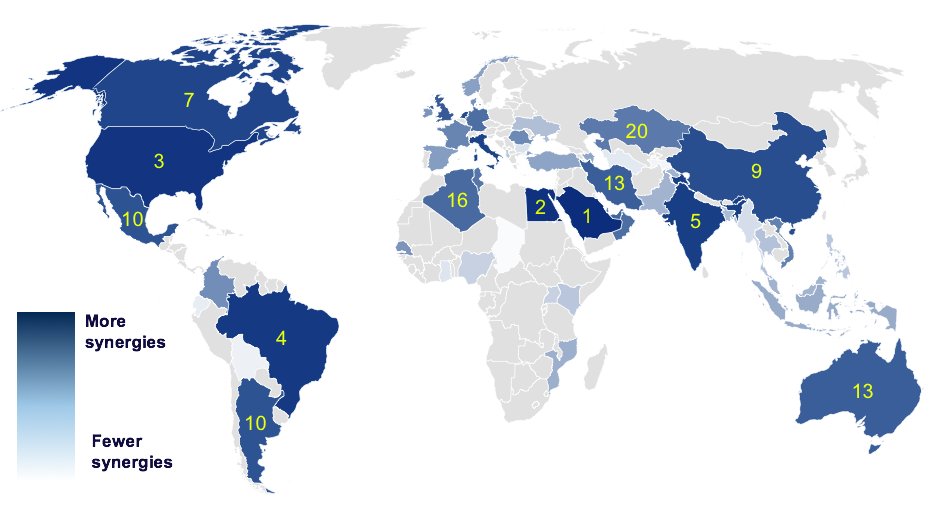

WoodMac also notes that certain regions have lower barriers to entry for majors interested in wind and solar.

Source: Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables

The consulting company sees synergies in areas where majors have already invested significant time and capital to develop their traditional operations, like Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Brazil.

Heggarty at WoodMac said companies will ultimately have to decide when and if the transition fits with their business. According to Goldman, majors should play a significant role in de-carbonization, and transitioning their business offers a way to engage with the changing energy landscape while remaining competitive.

But financial reports like that of Exxon suggest the change may be halting until majors can get a handle on the economic benefits. Kretzschmar says it will take time.

“Diversification into renewables is a difficult business proposition for the majors,” she said. “The key challenge for them is how to create value from these renewable investments. […] It’s a challenge for their CEOs: how to keep their shareholders happy and also make sure the business transitions into the low-carbon future.”