Remember when everyone talked about grid parity?

The term had a mystic connotation. It implied a specific moment in time when renewables would suddenly become cheaper than coal and natural gas -- and the notion that when the cost crossover occurred, the electricity system would be transformed into a low-carbon paradise.

The term has fallen out of favor for a couple of reasons.

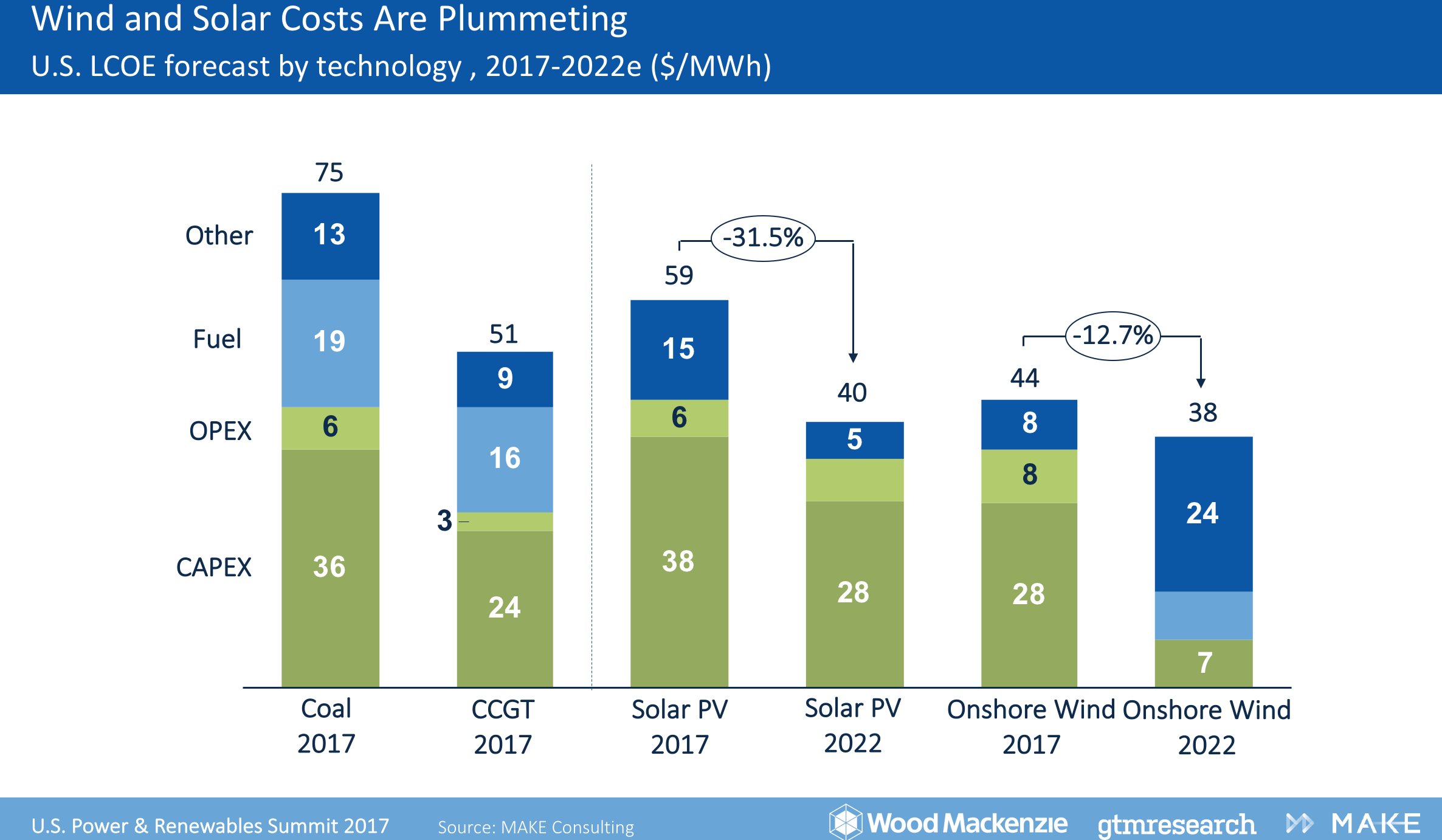

The most obvious one: wind and solar are basically the cheapest resources around. We're already at parity in most regions. That's why America is pretty much only building wind, solar and natural gas these days.

It's impossible to see how that trend gets reversed, given where costs are headed.

As Dan Shreve, a partner at MAKE Consulting, put it at our recent Power & Renewables Summit: "There's still more to come."

"When we start talking about renewables reshaping the power market, it really does boil down to the fact that renewables have become so much more competitive versus traditional fossil fuel generation sources in the United States," said Shreve. (Lucky you: Squares get to watch every single panel discussion from that conference for free.)

Target achieved? Well, not exactly. This brings us to the second reason that the metric of grid parity isn't used very often: It's a moving target. It's kind of a meaningless term.

Yes, costs continue to slide downward. But wind and solar aren't developed in a vacuum. As ever-cheaper but variable renewables hit the grid, they depress wholesale prices -- making each incremental unit of non-dispatchable wind and solar less valuable to the system. Coal, nuclear and natural-gas plants are under severe financial pressure as a result. But renewable energy projects will feel the same pressure.

Consequently, attention is shifting from grid parity to market design.

Now that wind and solar are past the point of no return, how do we design a system to maximize the value of those resources? Low generation cost is just one factor to consider. Suddenly, flexibility and dispatchability are becoming far more important, particularly in states like California and Hawaii, where grids are already saturated with renewables.

Perhaps we should be using another term: grid disruption.

The coming disruption of power markets is now a central focus for GTM. In collaboration with our parent company, Wood Mackenzie, and our sister company, MAKE Consulting, we're grappling with the tough questions about market design in a world with 20 percent, 50 percent or 80 percent renewable energy.

Wind and solar are not yet at 10 percent generation in the U.S. (solar is around 2 percent; wind is around 7 percent) and they're already changing power market dynamics in major ways.

"We think that renewable energy and power markets are on this inexorable collision course," said GTM's Shayle Kann, outlining those changes at the summit earlier this month.

"That can be a good thing or a bad thing," mused Kann.

California is the nexus of this collision.

Neither good nor bad....just different

Referring to California's solar surge, one attendee at the summit called the state a "science experiment."

California certainly offers a unique case study on how PV is reshaping wholesale markets here in the U.S. -- literally reshaping them.

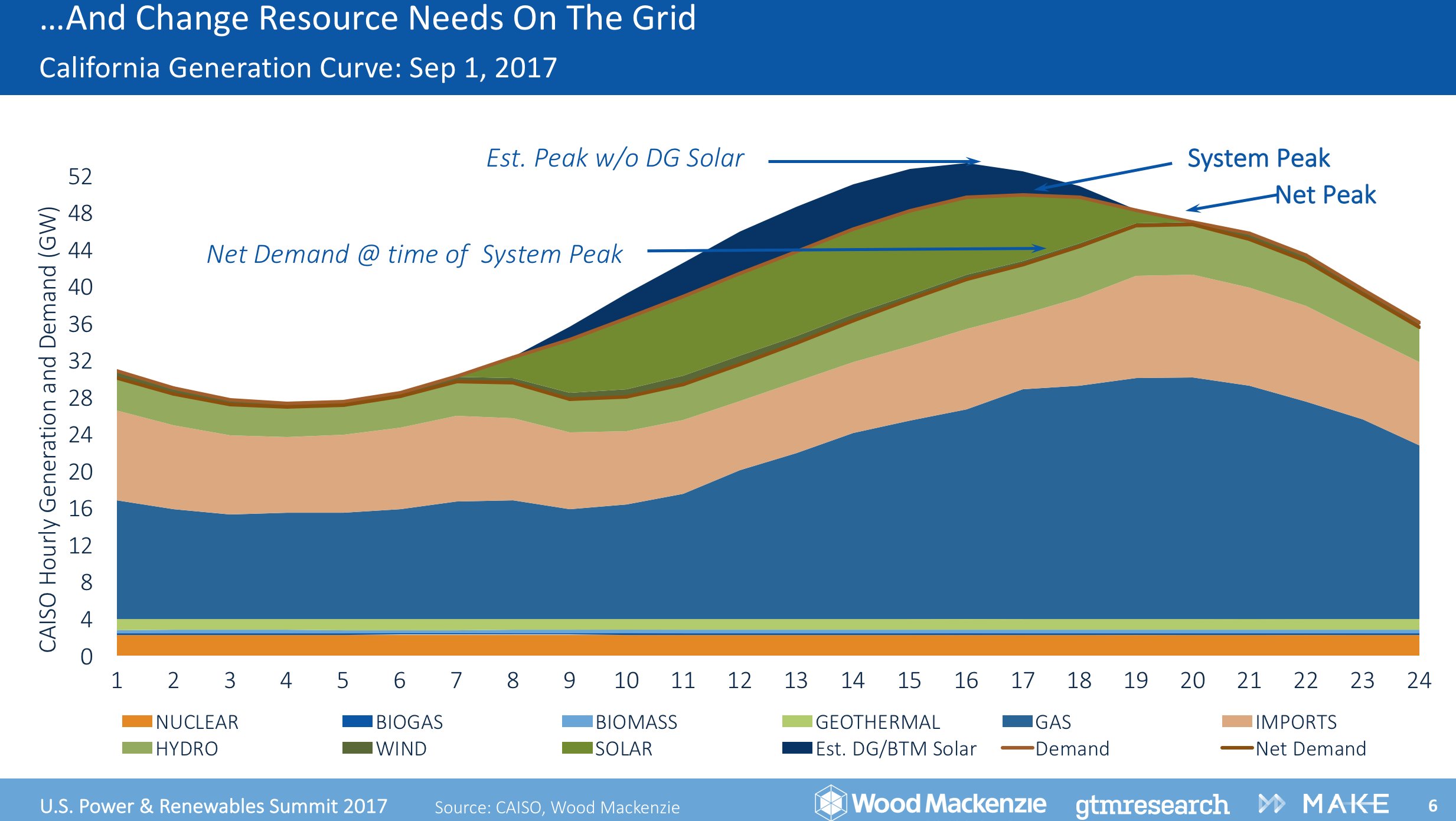

Prajit Ghosh, head of power and renewables research at Wood Mackenzie, put up a slide illustrating California's generation curve from September 1 of this year. That day featured the highest peak demand of 2017.

Notice anything? Solar suppresses the normal afternoon/evening peak. But when multiple gigawatts of PV capacity starts dropping off in the late afternoon, the net peak jumps up at 8 p.m.

In steps natural gas.

What does that mean exactly?

"What that means from a system planning standpoint is that you're thinking about 8 p.m. and not 4 p.m.," said Ghosh. "Now what happened at 8 p.m.? We know there wasn't a lot of solar and wind available in that timeframe."

Here's what happened: The system operator dispatched 11 gigawatts of imports and 26 gigawatts of gas. "That's what kept the lights on in California."

But Ghosh brought up a much more pressing question. If gas plants get priced out of wholesale markets because of super-cheap wind and solar (which is starting to happen), what happens to the system's ability to handle all that wind and solar?

"Now you think about a future where you get more and more renewables in the system. As power prices keep falling, it's harder and harder to keep these gas plants around. So suddenly you might be in this situation where a lot of these gas plants are not around."

Batteries are one option to replace gas, of course. Utilities around the country are increasingly turning to battery storage as a competitive alternative to gas peaker plants, albeit in limited amounts. But it would take exponentially more investment in storage to make up for lost natural gas in California, said Ghosh.

"You'd need billions and billions of dollars of investment in battery storage just to solve the issue," said Ghosh. "This is what power markets need to think of -- how much solar do you need? How much solar and storage do you need? How much gas do you need?"

With California barreling toward a 50 percent renewable grid, those are not theoretical questions. They are existential.

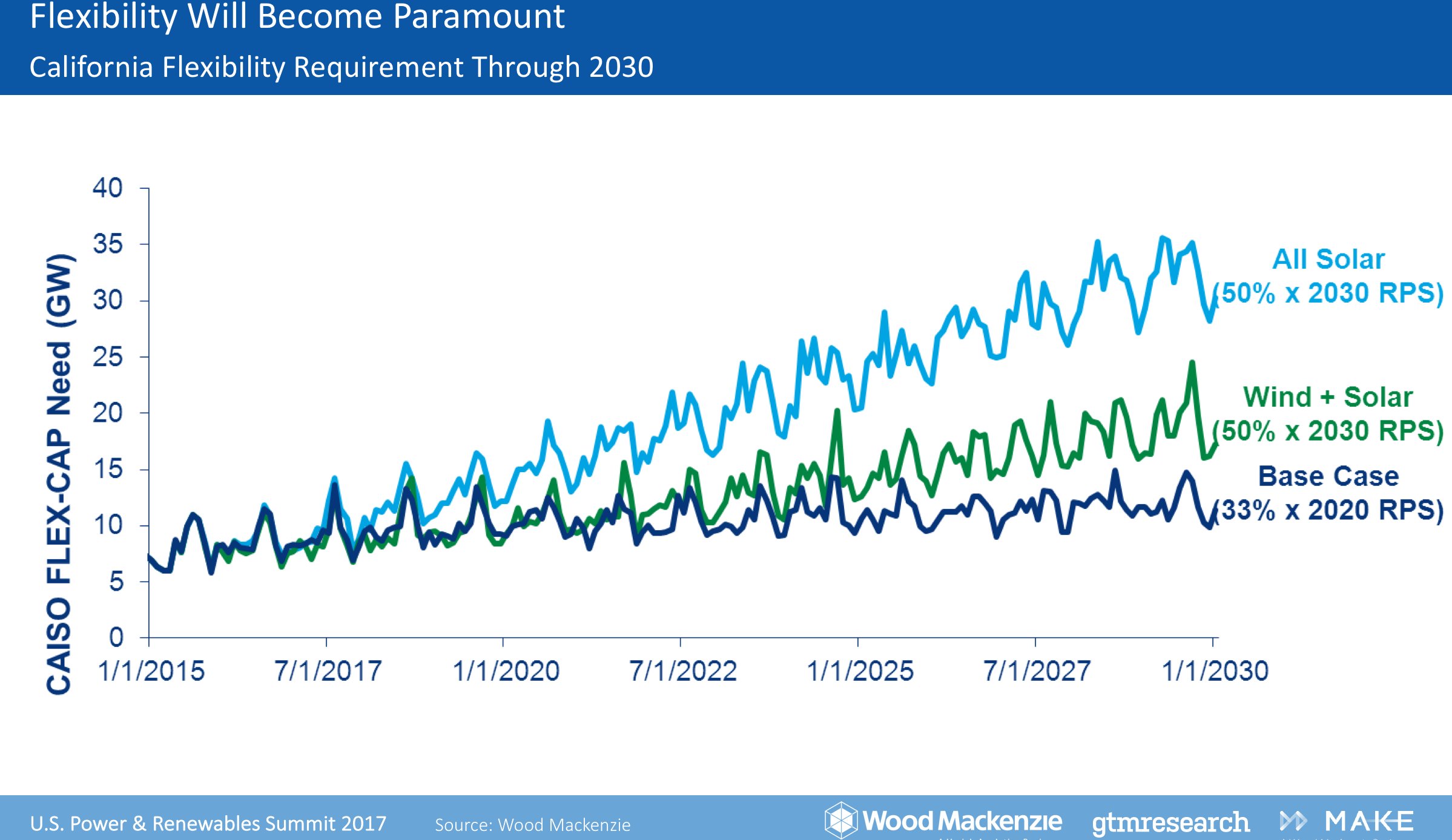

The state's interconnection queue is currently dominated by solar. If all incremental RPS requirements are met with PV, then flexible capacity needs would need to double in order to accommodate all that variable generation.

And if gas plants are priced out of the market, then batteries, demand-side management and regional imports become even more vital.

California is often called a "postcard from the future."

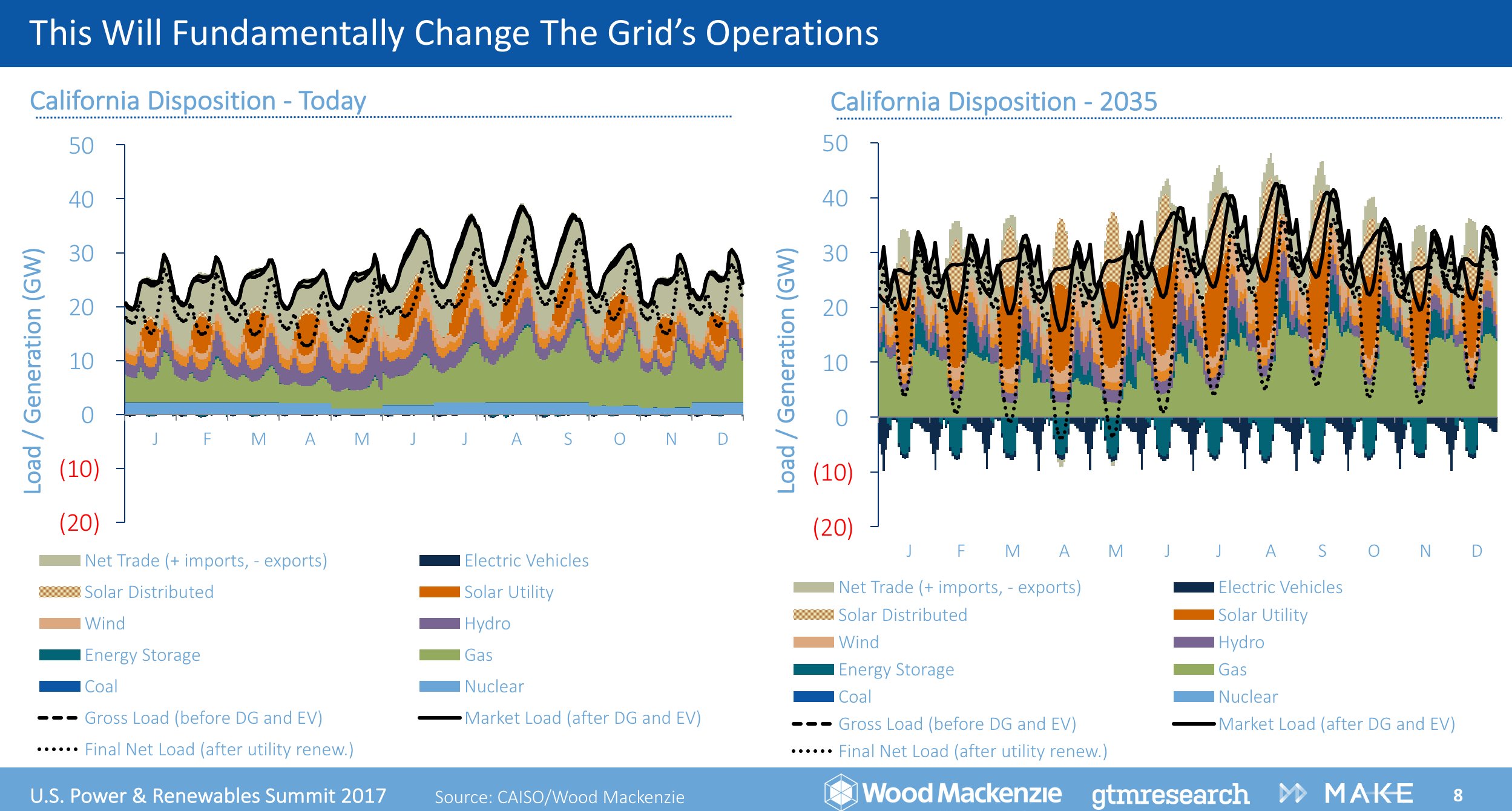

So Ghosh traveled to 2035, wrote a postcard from CAISO's control room, and sent it back for comparison.

The future is recognizable, but very different. "The difference is that a lot more is happening in 2035." There's a lot more wind, solar, electric vehicles; fewer exports and imports; and much greater reliance on storage. Gas is still an important feature of both grids.

"As you get further down this road, it changes the entire generation portfolio," said Ghosh.

Never mind 2035. We're entering a whole new world today.

Renewables are already pushing down wholesale power prices, putting pressure on conventional generators. That will eventually erode the economics of renewables that aren't developed with batteries.

Grid parity is no longer the issue. Grid restructuring -- how we brace markets for a flood of wind and solar, and how we build those projects to become dispatchable -- is the real issue at hand.

"To make it all work, you really have to think about how grid operations will function," said Ghosh.

Listen to us riff about market design on The Interchange podcast. We also feature commentary from Prajit Ghosh and Dan Shreve.