Chalk up another set of data points in favor of wind power’s cost-effectiveness against its mainline competitors of coal and hydropower, from both sides of the Atlantic.

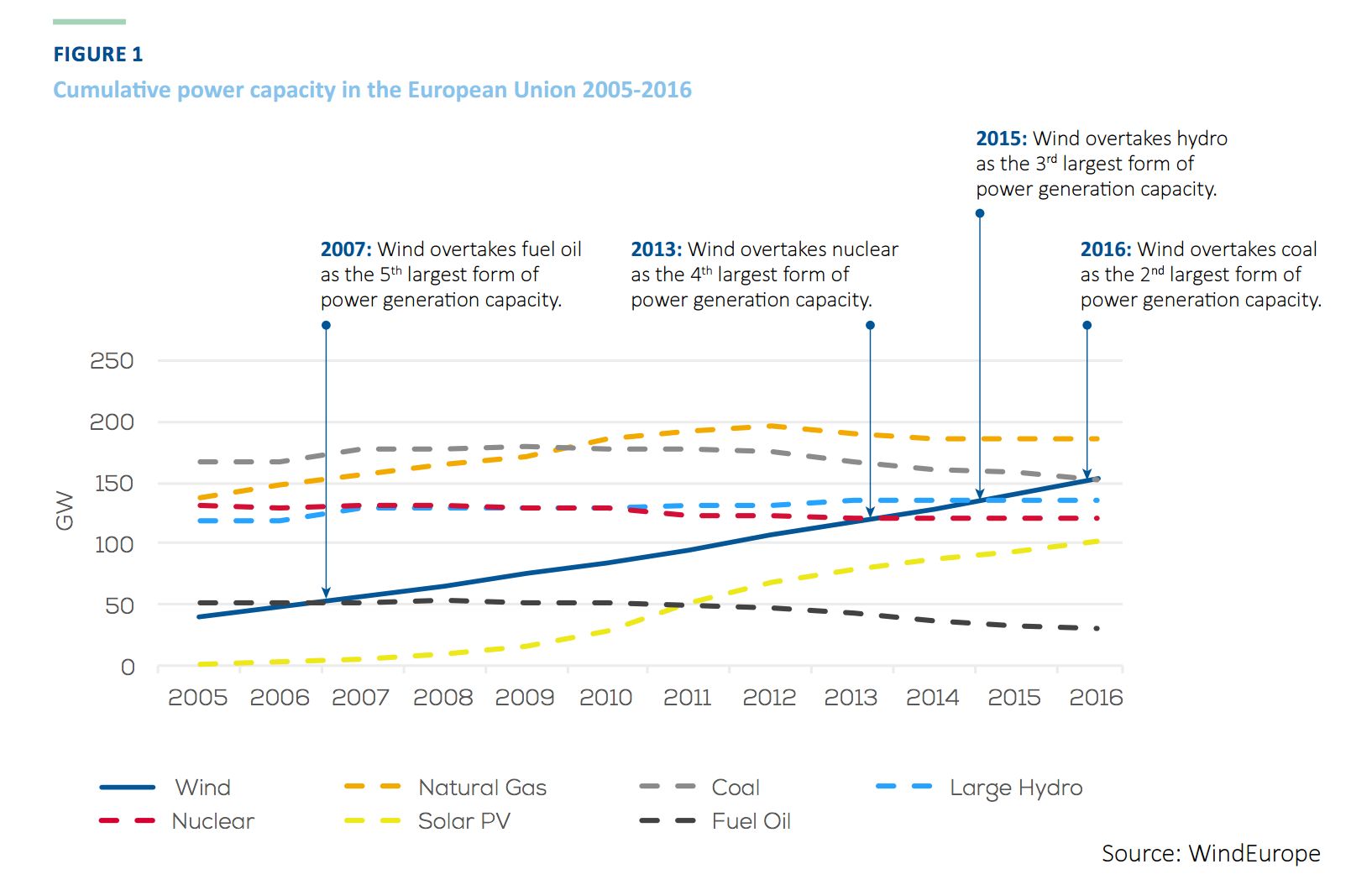

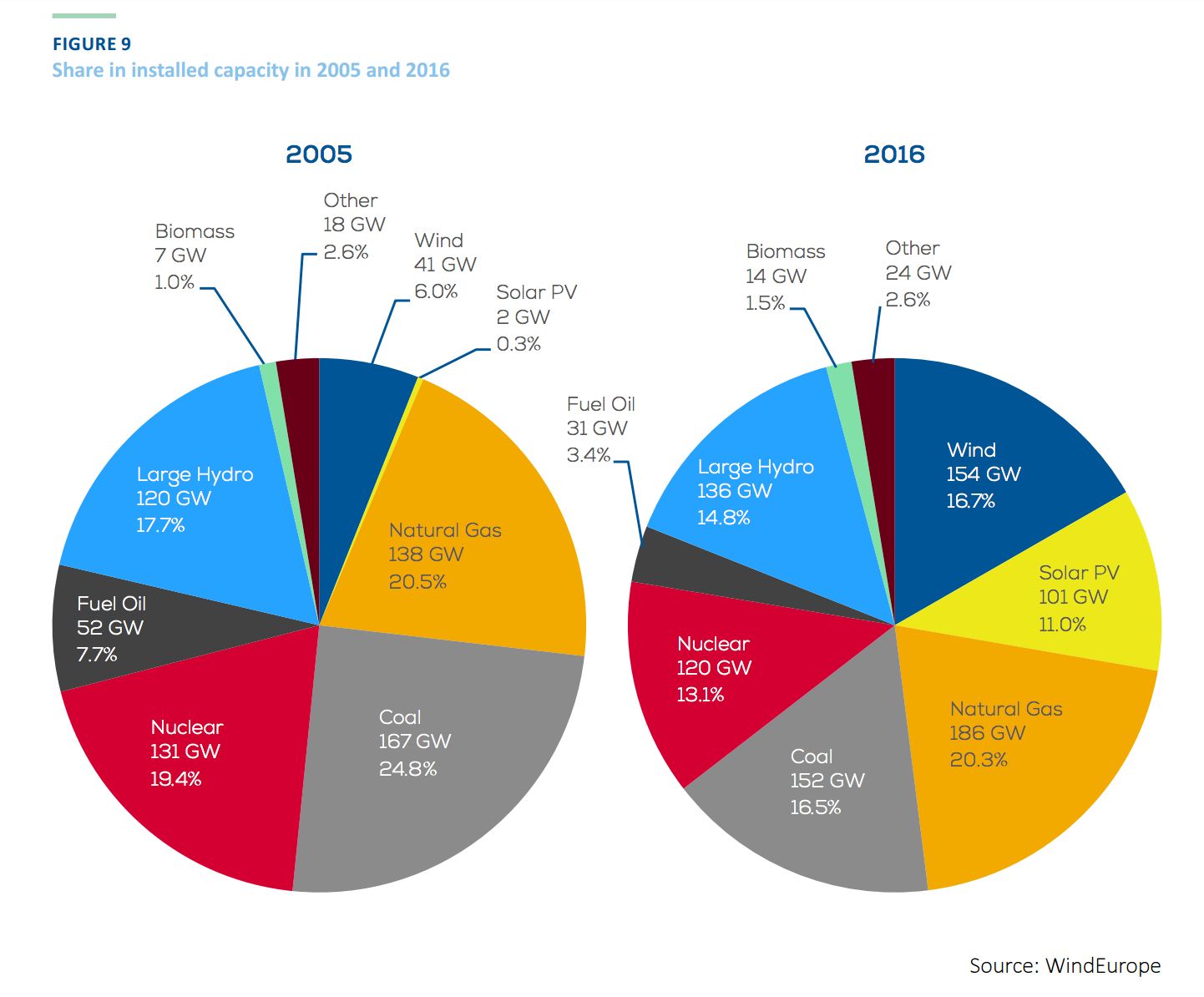

Last week, Europe’s wind power association WindEurope released its 2016 annual report showing that the continent’s wind turbines, which had already overtaken fuel oil, nuclear power and hydroelectricity in terms of installed capacity, have now overtaken coal to become the second-largest resource behind natural gas.

Wind power accounted for 51 percent of all of Europe’s new capacity last year, at 12.5 gigawatts -- about 11 gigawatts onshore and about 1.5 gigawatts offshore.

This new capacity brings wind’s share of Europe’s total capacity to 153.7 gigawatts -- 141.1 gigawatts onshore and 12.6 gigawatts offshore -- or just about 17 percent of the EU’s total energy capacity.

Germany continued to lead the European Union in wind power installations, with France and Benelux placing second, and the Nordics, U.K. and Ireland tying for third. In terms of installed wind capacity as a share of total energy consumed over the year, Lithuania led the EU at 16 percent, followed by Ireland at 13 percent and Germany at 10 percent.

The rise of wind as a major grid supplier isn’t new to Europe -- countries like Denmark have been dealing with it for years now. An ample supply of flexible hydropower in Scandinavia has helped northern Europe balance the intermittency of this wind resource, though not without its occasional hiccups. On the broader scale, however, wind power has joined with solar power to eat away at the profitability of conventional resources such as gas-fired power plants.

Meanwhile, back in the United States, the American Wind Energy Association's fourth-quarter 2016 report celebrated the country’s first offshore wind project, and the milestone of wind beating out hydroelectric resources as the country’s top green resource.

Wind power now provides 82.2 gigawatts of installed capacity in the U.S., just edging out hydropower’s 80 gigawatts, AWEA noted. This imbalance is partly due to a drought-driven downturn in hydroelectric generation.

But it’s a milestone nonetheless, given that wind turbines can be brought on-line so much faster than new dams.

It’s important to note, however, that wind power’s nameplate capacity isn’t the best way to measure its share in keeping the grid humming. Measured in terms of capacity factor -- the ratio of a generator’s annual power production to nameplate capacity -- wind power’s best performance is in the 34 percent range, while hydroelectric power stands at about 40 percent.

But as drought and environmental action impede hydro’s ability to perform, and as wind power technologies eke out single-digit gains in generation efficiency, those standings are set to reverse in the next two to six years, according to this analysis from Wood Group. Demand response is already being tapped in ways that support wind capacity and cushion unpredictability, and energy storage could begin to do the same thing, if it can compete on cost and efficiency terms.

State by state, Texas maintained its monster lead to break the 20-gigawatt barrier last year, with Oklahoma, Iowa, Kansas and North Dakota also adding significant amounts of wind capacity. Nationwide, the fourth quarter of 2016 saw 6.5 gigawatts of new wind capacity brought on-line -- the second-strongest quarter on record -- helping to bolster an otherwise slow year.

Meanwhile, the 30-megawatt Block Island wind farm marks the country’s first foray into large-scale offshore wind, though it’s set to be dwarfed by the larger projects being planned for the mid-Atlantic coast.

New York's first offshore wind push will be a 90-megawatt project 30 miles southeast of Montauk, to be delivered to the Long Island Power Authority, and New York state has identified a much larger region, roughly equidistant to Long Island and the Jersey Shore, that could add up to as much as 800 megawatts of capacity.

As for U.S. wind versus coal, the Trump administration’s vows to revitalize the increasingly uncompetitive U.S. coal industry is coinciding with market forces that could make coal more cost-competitive in the short term. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported this week that rising natural-gas prices should lead to an increase in coal-fired electricity over the next two years. Even so, last year’s coal production was the second-lowest on record since 1978, the EIA reported in its short-term energy outlook.