Things are moving quickly at the Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, the not-for-profit cooperative power supplier whose members serve more than 1 million people in four Western U.S. states.

Only a year ago, Colorado-headquartered Tri-State was a coal-dependent wholesale electricity provider watching as its members considered withdrawing from its service one by one. Several member co-ops hoped to exit to seek an alternative offering more renewables and cheaper resources, while Tri-State stuck by its contention that a transition was still too expensive.

But last July, the Western co-op announced plans to reform its energy supply plan. After further teasing its forthcoming changes and promising to abandon coal altogether by 2030, the company’s CEO last week pitched a transformed and decarbonized portfolio at the Colorado state capitol, during a press conference attended by Gov. Jared Polis, who’s characterized himself as a clean energy champion.

“We’re not just changing direction; we’re emerging as the leader of the energy transition,” said CEO Duane Highley. “We are favorably positioned to successfully transition to clean resources at the lowest possible cost.”

The marked turnaround shows just how rapidly the energy transition is moving. Plenty of natural-gas plants are still getting built, but the Energy Information Administration last week forecasted that renewables will make up three-quarters of expected U.S. capacity additions in 2020.

Utilities are increasingly jumping onboard. The move from Tri-State, until recently a symbol of the utility transition holdout, suggests more of its slow-moving peers may soon accede to similar pressures.

Tri-State's transition plan

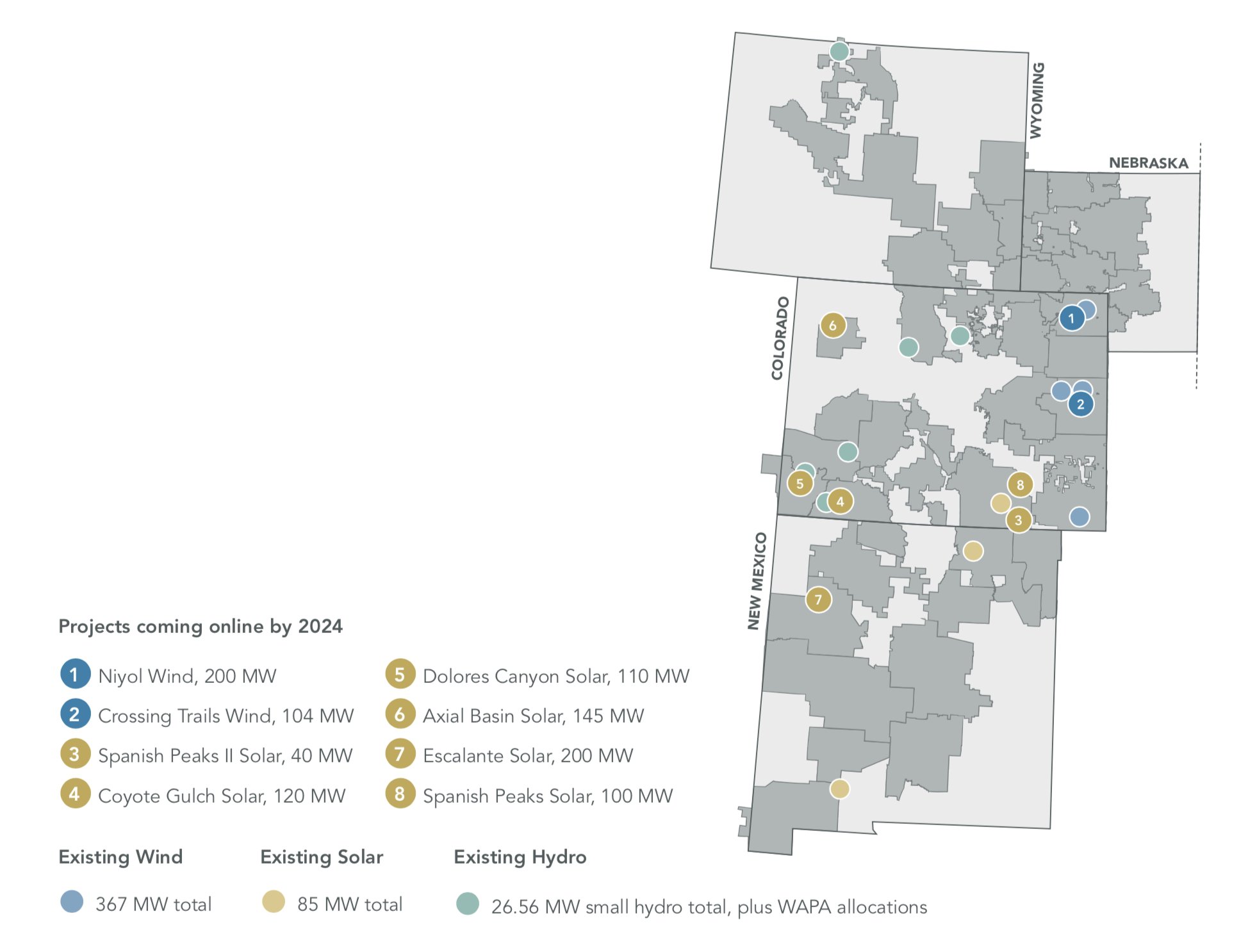

Over the next four years, Tri-State will add more than 1 gigawatt of utility-scale renewable generation to its portfolio. Large-scale solar projects in Colorado and New Mexico will account for 715 megawatts of that total, with the remainder to come from two new wind farms in eastern Colorado.

Taken together, the installations will increase renewable electricity provided to Tri-State’s 43 electric co-op members to 50 percent by 2024, up from about 31 percent in 2019.

Source: Tri-State

Meanwhile, Tri-State plans to retire all of its coal assets by 2030; in 2019 coal accounted for about half of the co-op’s generation.

Those efforts will put the co-op in line with two state policies passed in 2019: Colorado’s HB 19-1261, mandating the state cut emissions 90 percent from 2005 levels by midcentury, and New Mexico’s SB 19-489, which requires zero-carbon electricity by midcentury. Tri-State’s co-op members serve mostly rural customers, in those two states as well as Nebraska and Wyoming, neither of which have renewable portfolio standards.

Some members still considering leaving

While Tri-State’s most recent shifts have won applause from policymakers and environmentalists alike — the Colorado Sierra Club said the move means Tri-State is finally catching up to other Southwestern utilities — the road to get there wasn’t smooth.

Around the same time the co-op was working up plans to reform its energy plan, two members, United Power and La Plata Electric, began investigating how much it would cost to withdraw from Tri-State. Two other members had already been granted exits. Meanwhile, Tri-State was pledging to close some coal plants and add renewables to its portfolio.

“Tri-State is a cooperative that is owned and governed by our members, and our members desire a cleaner, more flexible and more competitive power supply,” Lee Boughey, a Tri-State spokesperson, told GTM. “The changes that transformed Tri-State…are responsive to our members’ needs.”

Despite the changes, La Plata and United are moving forward with their inquiry about exit charges — though United has hinted at the possibility that it will choose to stay.

Serving 43 members and 1 million customers spread out over rural areas means navigating a tangle of diverging motivations and policy objectives. Regulators in the states it serves had jurisdiction over Tri-State's rates and wholesale contracts until recently; in September, Tri-State added a natural-gas supplier to its stable of members, pushing it under the jurisdiction of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Those dynamics, along with pressure from members, compelled Tri-State to build more flexibility into its new energy plan. Members agreed last year to allow co-ops to generate more than 5 percent of their generation locally and get another 2 percent from community solar. A coalition of members is currently at work on more flexibility options, called partial requirements contracts, that will allow more local generation. Tri-State expects those recommendations to be presented to the board for a vote in April.

Tri-State stands among a rapidly growing list of U.S. utilities with ambitious transformation plans for the coming decades. Duke Energy plans to hit net-zero emissions in 2050; Missouri’s Ameren seeks to reach emissions cuts of 80 percent by that same year. In the West, Xcel Energy will cut emissions 80 percent by 2030 and Public Service Company of New Mexico will cease coal generation by 2031 and go emissions-free by 2040.

Tri-State’s goals now rank among the more aggressive utility plans. By 2030, Tri-State’s moves will result in a 90 percent reduction in carbon emissions for the co-op’s generation facilities in Colorado and a 70 percent decrease in carbon emissions for its wholesale electricity sales in the state.

Boughey said the co-op would cut all coal emissions in New Mexico by 2020; a new state law there mandates zero-carbon electricity by 2050.

Lingering role for natural gas

Many utilities settled on their new goals outside the purview of state policy, citing improved economics. Tri-State notes that its new plan means flat or lower electricity rates for members. But Tri-State’s commitments are undoubtedly linked to requirements in half the states it serves. Similar pressures have compelled coal exits for utilities such as Avista and PacifiCorp, companies with customers in Washington and California, which have 100 percent carbon-free targets.

Forced or voluntary, those commitments evince a greater embrace of climate action on the part of utilities than in the past. But it’s worth noting that most of these plans are geared toward the long term and leave flexibility for companies to determine the speed of the transition. Overall, the transition Tri-State has committed to is slower than the hypothetical pace studied in an analysis Rocky Mountain Institute conducted in 2018, which found that Tri-State could see significant savings if it exits coal by 2026. At the time of that analysis' release, Tri-State told GTM it was already taking advantage of low costs for renewables to deliver reliable and affordable power.

Tri-State’s reluctance to embrace such drastic change appears to have dissolved. But the co-op is still holding onto some traditional baseload resources; Boughey said natural gas remains part of Tri-State’s energy mix. Though Tri-State has no specific plans to add more — and it accounted for just 3 percent of its energy in 2018 — Boughey said the phaseout of coal has encouraged natural-gas purchases.

“As we’ve been reducing the coal that we use, we’ve been increasing the natural-gas portion of our portfolio as well as the market purchases in our portfolio,” said Boughey.

Right now, the company isn’t committing to leaving natural gas behind. Boughey said Tri-State will file resource plans later in 2020, which will determine plans for any added generation going forward.

While natural-gas emissions are lower than those of coal, the reluctance to leave gas altogether pokes at a lingering tension in the energy transition.