Community solar has become an increasingly popular way for electric utilities to bring solar to customers.

In 2010, there were only two shared solar projects in existence. Today, 77 utilities administer more than 110 projects across 26 states, accounting for a total capacity of about 106 megawatts, according to a new Deloitte report.

For many customers, going solar is viewed as a cost-effective, environmentally friendly way to buy electricity. A recent Deloitte survey of 1,500 household decision-makers found that 64 percent ranked “increasing the use of solar power” among the top three energy-related issues most important to them in 2015, up from 58 percent in 2014.

But many customers are prevented from installing solar on their own homes due to low credit scores, roof shading or because they don’t own their home. Due to these factors, 77 percent of U.S. residential households are likely ineligible for rooftop solar.

For solar installers, community solar is an opportunity to unlock previously unreachable solar demand. SunEdison launched its first shared solar program in National Grid’s Massachusetts territory last year. SolarCity announced a shared solar program last year, too. And smaller companies like Clean Energy Collective are leading the market with specialized services, such as billing software that serves multiple solar offtakers.

For investor-owned, municipal and co-op utilities, the opportunity that shared solar represents is less clear, but increasingly significant, according to Deloitte’s report, “Unlocking the Value of Community Solar.” Community solar allows utilities to expand their solar generation portfolios to help meet renewable portfolio standards or optimize the grid. It also allows them to bundle products and services to expand their business offerings.

For example, the Minnesota-based co-op Steele-Waseca Cooperative Electric (SWCE) allows customers to buy a portion of a shared solar project at a discounted rate if they also install a new electric water heater. Excess solar power generated during the day is used to create hot water so that homes avoid pulling electricity from the grid at peak times and putting a strain on the system.

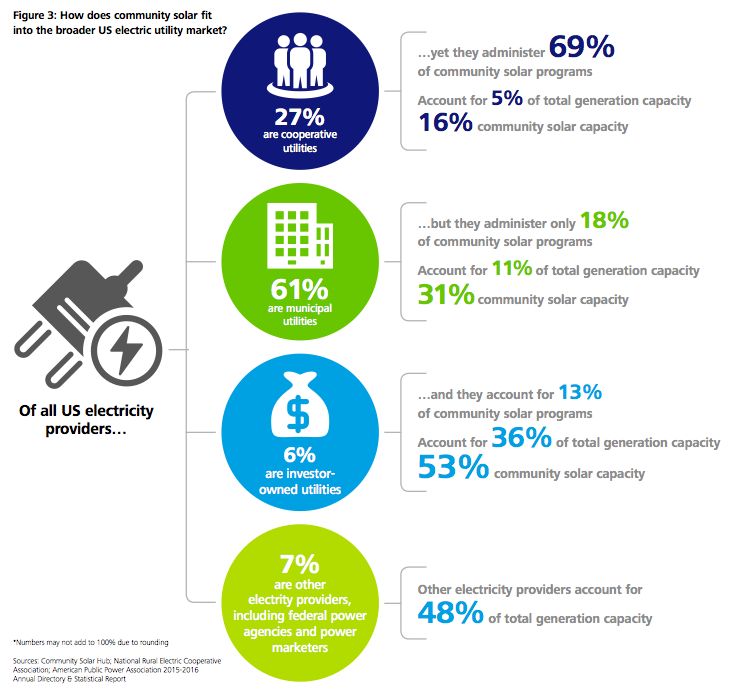

But while opportunities exist, the growth trends vary depending on utility type.

Co-ops represent only 5 percent of the nation’s total electricity capacity, yet they administer 69 percent of community solar programs. The report says this is a testament to strong customer demand for solar, and to co-ops’ ability to deploy solar programs more swiftly than investor-owned utilities. But because the projects tend to be smaller, co-ops account for only 16 percent of shared solar capacity.

A downside for co-ops is that they can’t take advantage of the federal Investment Tax Credit as nonprofit entities. So to capture that incentive, they generally opt for third-party ownership. This is part of the reason why projects tend to be smaller: “For systems under 2 megawatts, the lease buyout structure -- where the co-op initially leases the project from the developer, but has the option to buy the project for fair market value after a certain period of time -- is frequently the best option,” the report states.

Municipal utilities account for 11 percent of electricity capacity, and 18 percent of shared solar programs, representing 31 percent of community solar capacity. These projects are generally made possible by state tax credits and other incentives, such as California’s cap-and-trade reinvestment program -- and by taking advantage of community property.

Investor-owned utilities (IOUs) represent a relatively few shared solar programs, but those with programs have developed them in a big way. IOUs represent 36 percent of total electricity capacity and 13 percent of community solar programs, which amounts to 53 percent of community solar capacity.

There are still a few “kinks in the system” when it comes to IOU-administered programs. For instance, interconnection standards designed for distributed energy resources can be a challenge.

However, regulators in several states are actively working to reduce barriers and create new incentives. According to Deloitte: “As the kinks in the system begin to get ironed out and more resources become available, it’s likely that the role of IOUs in this market will become increasingly significant over the next several years.”

Recent reports, such as the Low-Income Solar Policy Guide and the Interstate Renewable Energy Council’s low-income solar guidelines, have detailed how regulators and policymakers at various levels of government can create successful models for shared solar.

Deloitte created an interactive map to see which states have policies and regulation in place to support shared solar, available here.