The United Nations has an ambitious goal of bringing sustainable energy to all by 2030. But according to a new report from the International Energy Agency, that effort is not going very well.

Four years into the initiative Safe Energy For All (SE4ALL), the progress is “substantially short” of what will be required to meet the goals by 2030, the report states.

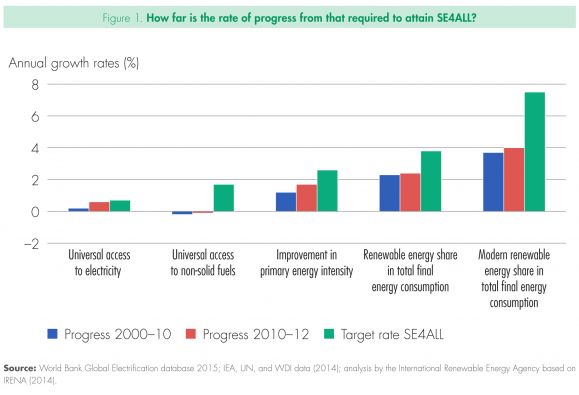

There are three overarching objectives in the framework: providing universal access to modern energy services; doubling the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency; and doubling the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix.

All of the areas are coming up short, but universal access to non-solid fuels has seen the least progress.

Although renewable energy is the fastest-growing portion of new electricity generation in many countries, its rate of growth is still not fast enough to meet the UN goals and unseat legacy sources of generation, primarily coal.

There are positive signs in some areas. From 2010 to 2012, an additional 222 million people gained access to electricity, with about a quarter of the newly electrified households being in India.

The challenges and complexities are immense, the report notes. Sub-Saharan Africa has seen little progress, and electrification has only managed to stay abreast of population growth.

“If we continue electrification at the rate we are going today in Africa, there will be more people without electricity by the end of the decade,” said Anita George, director for energy and extractives global practice at the World Bank, during SunEdison’s Eradicating Darkness event earlier this year.

More importantly, the very meaning of energy access needs to be redefined. In many countries, a grid connection does not guarantee regular electricity service. In some areas that report high rates of electrification, the real figure may only be one-third of that due to frequent blackouts. Delivering reliable service at affordable prices, usually displacing the cost of diesel for generators, will be critical to meet the goals.

In the developed world, progress on energy efficiency is better but still falling short. Stefan Heck, consulting professor at the Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford Law School, said at the SunEdison event that the U.S. wastes enough electricity annually to power the U.K. for seven years.

Even so, the U.S. was one of the top eight countries that exceeded the 2.6 percent reduction in energy intensity. Much of the drop was attributed to heavy industry, with transportation coming in second.

Renewables are seeing a similar story in most of the world: some progress, but not enough. Only Nigeria, China, South Korea, the U.K. and Australia met the annual growth rate target of 7.5 percent. There is some sign that those numbers could improve. Last fall, the U.S. and China signed a non-binding climate deal that could offer support for more renewables.

The most value, however, could come from focusing on universal access to modern energy. The IEA estimates more than $1 trillion will need to be spent between now and 2030 to meet all of the SE4ALL objectives; however, only about $50 billion of that would be needed to bring clean cooking fuel and electricity to the 3 billion people who live without one or the other.

“This is not about charity. This is about markets and investments,” Kandeh Yumkella, CEO of the SE4ALL initiative, told delegates to SE4ALL’s second annual Forum in the UN General Assembly on Wednesday. “We see this as a trillion-dollar opportunity, not a trillion-dollar challenge.”